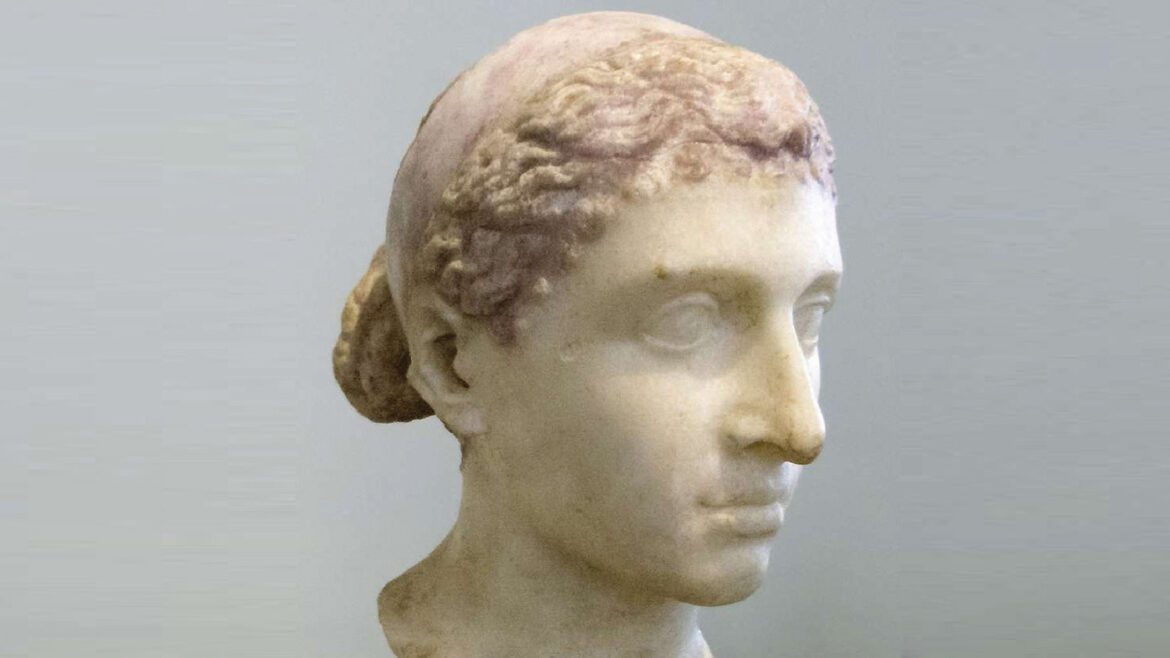

There are few female rulers whose reputations were dragged through the mud as thoroughly as Cleopatra VII. with most Roman historical sources only mentioning her looks and seductive charm, creating an image of Cleopatra as a manipulative temptress who ruined Antony, with Cassius Dio (42.34; 50.5), writing in the 3rd century CE:

“She was a woman of surpassing beauty, but she used it to ensnare Antony and make him her slave.”

While Roman poets scandalized her to the point of painting her as a sexually immoral madwoman whose defeat saves Rome – Horace (Odes 1.37):

“The insane queen, plotting ruin for the Capitol… drunk with sweet wine, hoping for great things.”

or likewise as a foreign witch whose erotic power turns Roman men into slaves – Propertius (Elegies 3.11):

“Rome, you were a slave to a woman… the whorish queen dared to look upon Jupiter’s thunderbolt.”

And even though Plutarch is more nuanced than the poets above, he still describes her primarily through the lens of seduction, reducing her political strategy to “irresistible charm,” implying manipulation rather than statecraft:

“Her beauty was not incomparable… but her presence and conversation were irresistible.”

(Life of Antony 27)

Posterity did not treat her much kinder, amplifying her image as a lewd, drug-addled seductress lounging around half-clad on lavish couches (Boccaccio ‘De Mulieribus Claris’), and even Shakespeare, who at least bestowed his Cleopatra with some complexity, could not resist using the trope of the bewitching seductress.

And while the most obvious explanation for this reputational onslaught is also the most predictable (“she was a woman”), there is a far more compelling explanation that ominously falls to the wayside wherever Cleopatra is characterized: Her exemplary leadership, which had already been the reputational undoing of great men like Scipio Africanus, who famously died in exile after saving Rome from destruction and being incessantly smeared by Roman politicians, with his last words: “Ungrateful fatherland, you will not even have my bones.”

In an ancient Mediterranean world that functioned – politically speaking – much like a sprawling corporate conglomerate fueled by ambition, military fame, and personal enrichment, Cleopatra managed all of the above while also doing something almost unheard of: she took the actual task of governing seriously. Not only do the ancient sources acknowledge that she was a formidable political actor (Plutarch Life of Antony 25–29; Dio Cassius 42.34–44; Strabo 17.1.11), but she also managed to pull Egypt back from bankruptcy, famine, and geopolitical irrelevance, leading it into one last, astonishing peak of prosperity and political significance.

When Julius Caesar arrived in Alexandria in 48 BCE amid the Roman civil war, he found Egypt locked in its own dynastic conflict with Cleopatra VII and her brother Ptolemy XIII’s armies at each other’s throats. Cleopatra, who had been recently ousted by her brother’s faction and forced to flee the country to regroup her army, arranged a clandestine meeting with Caesar and had herself smuggled into the palace under the cover of night. Now, Roman authors [Plutarch, Life of Caesar 48; Life of Antony 27] and Hollywood, for that matter, would have us believe that she dramatically rolled out of a carpet in a transparent gown and heavy make-up, but this narrative evaporates upon contextualization. Cleopatra took an extraordinary risk of immediate imprisonment or death with this secret meeting. Her brother’s regents had already shown their capacity for violence and her own sister Berenice IV had been executed by their father after leading an earlier revolt. Caesar, after all, had come to “arbitrate,” and it would have been far easier for him to hand her over to her enemies than to support her claim, and if he had wanted Cleopatra merely as a lover, as later folklore will have us believe, he could have kept her without reinstating her.

Cleopatra, however, was shrewd enough to know that Caesar did not back rulers because he found them attractive; he backed rulers who could stabilize strategic territories and repay debts, and he admired leaders who mirrored his own values of audacity, calculated risk, and swift, decisive action. So instead of waiting outside the city walls at the head of her army, stomping her little feet like her brother, she took matters into her own hands with this calculated move. Cesar’s ensuing support therefore signals something else: he recognized her as the more capable sovereign, one whose intelligence, rhetorical skill, and political genius would ensure the constant flow of much-needed grain to Rome and his political backing in the Roman civil war. And he proved to be right in backing her claim to the throne, although it came with grave risks for him and his troops, who were soon at the centre of an outright revolt against this decision to put Cleopatra on the throne (in co-regency with her brother no less and following the will of her late father Ptolemy XII.)

Unlike many of her predecessors, Cleopatra approached the task of ruling not as a birthright to be demanded by force, but as a job requiring competence, strategy, and relentless commitment.

Cleopatra’s reign is, above all, a study in courage. She consistently embraced personal risk, whether slipping into Caesar’s presence under cover of night, navigating the violent uprisings that shook Alexandria, or later negotiating with Antony in Tarsos. In every crisis, she chose decisive action over passive power play. She governed with unusual seriousness and capability: her reign saw economic reforms, currency stabilization, renewed irrigation, and decisive intervention during periods of famine and instability. Contemporary authors even note that under her administration, Egypt became profitable again (Strabo 17.1.11; Dio Cassius 42.35), after inheriting a kingdom on the verge of bankruptcy due to her father’s excessive spending. Far from serving as a decorative partner in Antony’s wars, Cleopatra commanded real naval power. She supplied the bulk of the fleet at Actium and personally oversaw its provisioning and financing (Plutarch Antony 62; Dio Cassius 50.13). Her political instincts preserved Egypt’s sovereignty longer than any neutral observer might have believed possible; surrounded by Roman client states, she leveraged diplomacy, wealth, and a charismatic political presence to keep Alexandria independent for two decades. And in the end, with Octavian’s victory imminent after the battle of Actium, she died as she lived, on her own terms, putting the famous asp to her breast, instead of accepting the degradation of being paraded through Rome as a trophy of war. Her suicide at thirty-nine followed the ancient heroic code of choosing dignity in defeat over spectacle in captivity (Plutarch Antony 85–86; Dio Cassius 51.14–15).

If we strip away the Roman narrative, the Hollywood fantasies, and the centuries of orientalist distortion, Cleopatra VII emerges not as a femme fatale but as one of history’s most capable leaders. She inherited a bankrupt, famine-stricken kingdom and turned it into a functioning, wealthy, culturally radiant state. She navigated the geopolitical hurricane of Rome’s civil wars with tactical brilliance. She commanded fleets, drafted decrees, negotiated alliances, built libraries, funded temples, and spoke more languages than any other ruler of her dynasty. Cleopatra’s real offense was not the inherent moral failure of her charm or beauty, or the fact that she was able to win over the loyalty of Caesar and Antony – two of the most powerful Roman men of her age; it was her superior competence as a stateswoman that earned her these salacious attacks on her virtue, and the mockery of her beauty and charms were but meagre attempts to explain her power and modern readers do not need to repeat that mistake.

Cleopatra, as the last great queen of Egypt, stands out as a female leader who, against all odds and scathing public opinion, chose to rule boldly, brilliantly, and on her own terms.

by Carla Berenice Groh

Carla is also a writer on Substack, where she explores Ancient Egyptian thought, ritual, and intellectual history. Her forthcoming book on Egyptian mysticism and philosophy draws on her academic background as an archaeologist and Egyptologist, with graduate training and research in material culture, intercultural exchange, and ancient literature.