Debra Austin was Invited by Balanchine to Join the New York City Ballet

That was Just the First Barrier this African-American Dancer Broke.

![]()

Debra Austin’s instructor decided that she lacked talent at the age of eight when she took her first ballet class. “When somebody says you cannot, I say I can.” That determination pushed Debra to continue, giving up weekends to practice and commuting by bus and train to the school. At 16, she became the first African-American female dancer at the New York City Ballet when George Balanchine invited her to join. It was there she learned to perfect her jump and became known for her ability to fly. Debra later joined the Zurich Ballet in Switzerland, before returning to the U.S. as a principal dancer for the Pennsylvania Ballet. Today, she is a Ballet Master and Founding Member of Carolina Ballet in Raleigh, North Carolina, where she teaches students that no one should ever stop them from doing what they’re born to do.

You are a world-renowned ballerina breaking many barriers along the way. How did you start your career?

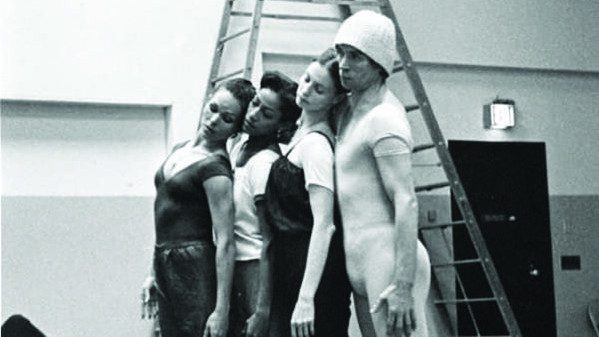

Choreographed by

George Balanchine,

Debra was part of the

original cast of New

York City Ballet’s Ballo

della Regina which

premiered in 1978.

PHOTOGRAPH BY STEVEN CARAS

My parents divorced when I was probably eight, so I did not really grow up knowing my natural father. My mother, who has since passed away, remarried, and my father, Lionel Austin, lives in New York. His influence, more than my mother’s, was the impetus for my starting ballet. He just loved dancing which is odd because he did not know anything about it. He never danced in his life. Ruthanne, my friend across the street, was doing ballet, and I asked my mother if I could take ballet with her. She agreed, and I went to the local ballet school. After about three months, the instructor told my parents I had no talent to which my father said, “If you think she has no talent at eight years old, I don’t know if you’re a very good teacher.” They sought out a ballet school that was housed in Carnegie Hall that had a wonderful children’s program. I really lucked out because the offshoot school was in the Bronx, and the woman who taught there was a soloist in the New York City Ballet, Barbara Walzach. From that point onward, I had good training. In hindsight, I was lucky that my parents were told I had no talent.

How involved were your parents in ballet in your formative years?

Every dancer’s parent is a part of their profession because the parents have to get you to class every day. When you are in the School of American Ballet, you are not allowed to miss one class unless you are deathly ill. If you are injured, you must be in class, sit, watch and take notes. It takes a lot for a parent to support ballet. We lived in Riverdale, which is in the Bronx. I used to take a bus and a train to get to the School of American Ballet and go to PCS (Professional Children’s School). It takes a lot of parental involvement.

Your first big break came when?

My first big break came when I auditioned for the Royal Ballet School. The Royal Ballet came to town with Rudolf Nureyev, ironically enough, and I was picked to be a mouse in the Nutcracker.

How old were you?

I was 10.

10 was a pivotal age for you because that was when you dedicated your life to dance, your raison d’etre?

Yes. It is so funny because when I first started, they enrolled me at the Children’s Ballet Theater, the school in Carnegie Hall, which was the offshoot school in the Bronx. They told me I had to take class three days a week, and on Saturday, we were required to take class and rehearse. I said, “What? Saturday? No, I play with my friends on Saturdays and don’t want to do ballet,” which of course was not an option. After I made the decision to dance on Saturdays, I never looked back, never thought I would rather be playing with my friends. My friends became my classmates.

You were known for your jumps. Is jumping physiological or psychological?

I think you are physiologically born to do jumps because I remember when George Balanchine came into the studio to see the B class (B class in the School of American Ballet is about 13 years old). He would come in and watch the younger ones just to see what we were like. He watched us grow up. One day when he came, there was a step called coupé jete, which men usually do. You jump off one leg, and you push around in a circle. It is a female set, but men are more known for it. That day, for some reason, the teacher gave us that step to perform in class. I think that step is what got me into the New York City Ballet.

Debra with Tamara Hadley, Suzanne Farrell and Rudolph Nureyev during a rehearsal of Balanchine’s Apollo.

Do you think the instruction was done purposefully to highlight your ability to jump?

Her name was Muriel Stewart, and she was one of Anna Pavlova’s apprentices. Muriel was one of 12 children that Anna Pavlova mentored. The step was not something that she usually gave. I am not so sure that she did not give it on purpose. You know, I never asked her.

Mr. B (George Balanchine) played a significant role in your career?

He was a father figure to all of us, especially, when we were young. He was larger than life, and it was so hard for me to even talk to him. I was fearful of him. One time, I slipped out of Sean Lavery’s hands, and I fell to the ground during a fouetté. Mr. B always stood in the stage right side wing. People used to say, you could see the outline of his nose if you really looked in that direction. Later that day, as I was walking home, I caught up to him because I walked faster than he did. I said, “I am so sorry. I am so sorry.” He said, “No, dear, falling does not matter. It means energy, energy.” He almost liked it when you fell because it showed that you wanted that jump to be big and to fly in the air. When he choreographed Ballo Della Regina, for me, he did the finale first and jumps in second position. When my solo came, he gave me those jumps from my solo. That is how it starts. He used to say to me, “Dear, do not listen to music, just jump, just jump.” I felt like he gave me Peter Pan’s strings and let me fly. Like in your dreams.

On a scale of one to 10, how important is discipline?

You must have a lot of discipline to be a dancer. 10.

Is discipline more important than God-given talent?

Yes. Because you can have given God-given talent, but if you are not disciplined, you will not make it. I have seen a lot of dancers go down that path too.

Where did that drive and discipline come from?

I am not really quite sure. Nobody has ever asked that question. I knew I was passionate about ballet. I chose ballet over playing with my friends on Saturday. When I was about 10 years old, studying in the School of American Ballet, they told me that I was never going to get into the New York City Ballet because they said I would have to be a soloist to dance there. It may have made me strive harder because I wanted to be a soloist.

Perhaps your drive comes from a belief or the desire to overcome when someone says you cannot do something. When is your first memory of being told you could not?

Exactly. When I was 12 maybe. In some crazy way, I was told often that I was not good enough to do ballet and that did make me strive harder. When somebody says, “You cannot,” I say, “I can.”

You broke through many barriers because of the color of your skin. Tell me the first time you realized that you were viewed as a young African American as opposed to a talented dancer.

When they told me that I was not going to get into the New York City Ballet because I would not fit in. I would not be able to be in a line of corps girls because I would stand out. I would not be able to blend. It made me say, “I am not going to let the color of my skin stop me.” What is the moral of that? No one should ever stop you from doing something just because of your looks; if you are Asian or your skin is a little darker, that is no reason to stop anyone from doing what they’re born to do. In some ways, to be a dancer, you need discipline as well as being born to be a dancer. You have the combination of being born to dance and the discipline to do it too. Why let somebody stop you from doing something that you are passionate about? It is not fair, but then I guess life is not fair. My mother used to tell me that all the time.

Why did you leave the New York City Ballet for Zurich?

At the New York City Ballet, I danced a lot of principal and soloist roles, but I just could not seem to break the barrier. I have been told by certain people that there was a little underhandedness that went on. When I visited my friend in Switzerland, I just loved being in Europe. We traveled a little bit, and I thought I can see myself there. I worked with George Balanchine in Zurich Ballet and danced Symphony in Three Movements. He chose me to dance the lead. I thought it was a good place to go because I did not fly too far away from the nest, and it was not some strange company. After two years, I was ready to come home.

Did you ever want to stop?

Stop dancing? No, I wanted to leave Zurich. I wanted to come back home because it was just too far. I was an only child. My mother had me when she was 19, and I was her little doll. We were awfully close, and at a point, I just had enough and decided it was time to go home. Peter Martins actually asked me if I wanted to rejoin the New York City Ballet, but I had been there before. He said to me, “I know someone who’s taking over a ballet company. The deal is not signed yet, but when it is, give me your number, and I’ll have them call you.”

Being a principal dancer lured you from New York City to Zurich. And then finally Mr. Weiss (Ricky) called, and you landed in Pennsylvania and Philadelphia as a principal dancer. Was that what you expected?

Zurich was wonderful too. I mean, I danced the principal and soloist parts there and in Pennsylvania. Rudolf Nureyev. Was he as fabulous as they say . . . the greatest ballet dancer of all times? I adored him. I absolutely adored.

You called him Rudy.

Rudy. Yeah.

Was he as temperamental as has been reported?

He was.

Were you scared of him?

No, not at all. He was so kind to me. I was a jumper, and I could do double tours. I would do them in class, and he would look at me and say, “Debbie, go show those boys how to do it.” It was so cute.

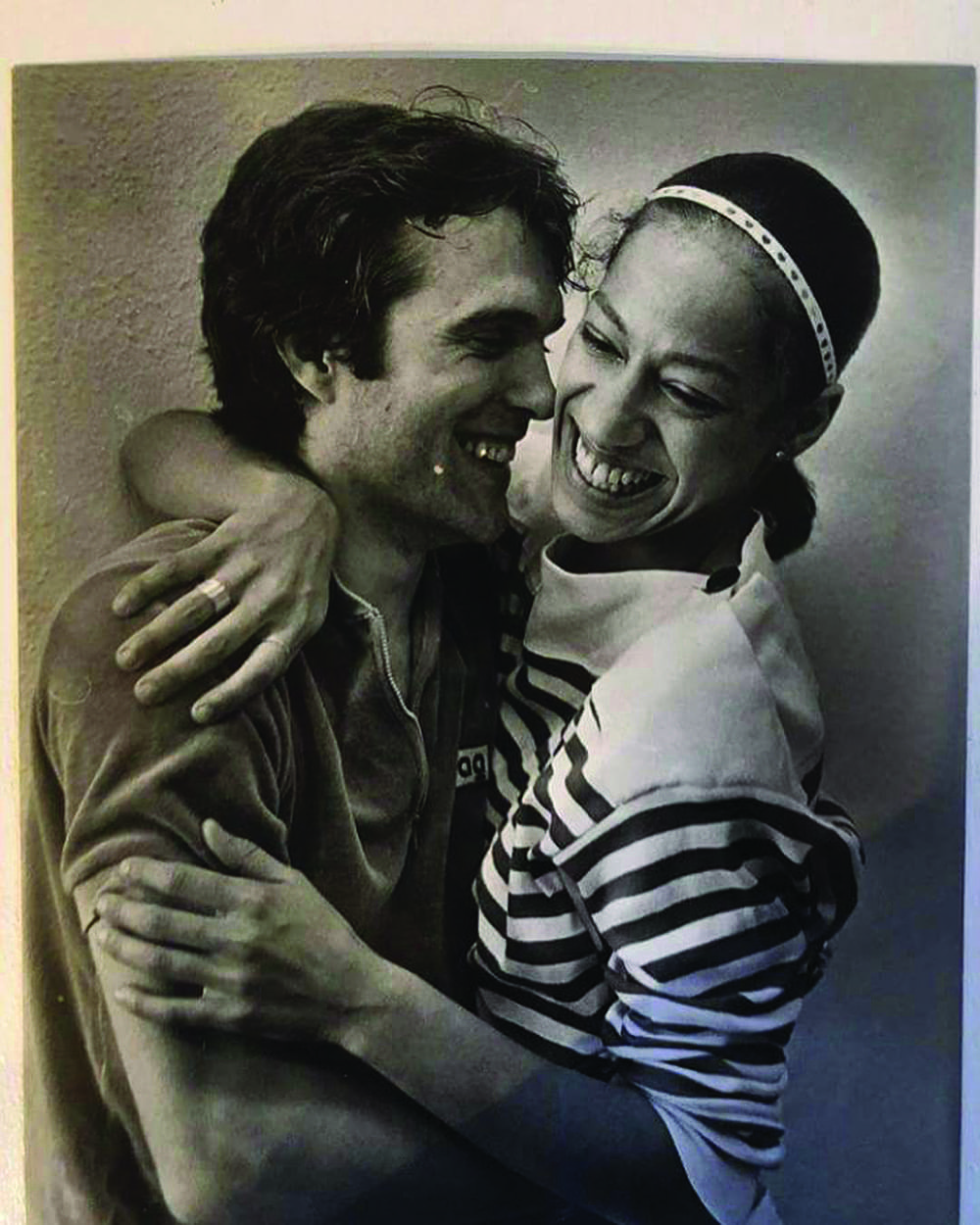

Debra with her husband, Marin Boieru, who she met at the Pennsylvania Ballet.

At what point did you meet your husband?

Pennsylvania Ballet. Ricky Weiss took Marin and me when he got the job as director in 1982.

When you saw him, did you know he would be your life partner?

Yes. He is the dearest person in the world, and he is my best friend.

Tell me about that moment when you first met.

We met in a ballet class. We arrived the same year I came back home. Sometimes on the weekend, I would come home from Philadelphia to visit my mom in New York City. He had a friend that lived in New York, and we would catch the train together. We started talking and then, game over. We went out to dinner, and the rest was history.

Were you paired?

No, he was paired more with Ricky’s wife, Melissa Podcasy. He is taller than me in shoes but not on point. We have danced a few things together, including a ballet which was a Spanish piece similar to Don Quixote. We also did Tarantella together but no major partnering. He danced with Melissa more than me, which was probably a good thing because partners sometimes fight.

In the Philadelphia Ballet, you were the principal. Tell me about that experience.

It was wonderful. I mean, Ricky was good to me. We had four or five principals, and we danced everything; the classics, Swan Lake, Coppelia, Giselle, La Sylphide, along with many of Balanchine’s and Robert Weiss’ work.

Is ballet mental or physical, and which is more exhausting?

I think they are equal. Sometimes it is more mental because when you do not dance well, you go home. You are your own worst critic. You feel like you were not as good as you would have wanted it to be. The audience might not know, but you know.

Why did you stop performing?

Ricky wanted the Pennsylvania Ballet Company to go forward, not backward, so he left. Marin became a guest with a dance company in Seoul, Korea. They hired us both and paid for everything which allowed us to keep our house in Philadelphia, go to Seoul, Korea and dance. When that job was over, it was time for me to decide whether to have a family or not. I was 34 or 35 years old at the time. We moved to Miami, and Marin danced for Miami City Ballet with Edward Villella, and I had Bianca, our first child.

Are decisions to have a family for professional ballerinas complex?

Yes. Now, a lot of dancers have children, but I was at the age where getting a job (age 35) was not as easy. I asked myself, “How many more years am going to dance?” I did not want to do a disservice to a company, … get a job, then get pregnant. I was at the point in my personal life that I felt I had to make a decision. It is possible though to do both. We have dancers in this company who have children. We have a principal dancer here who has two little boys. She danced through two pregnancies, had a baby, came back, had another baby, came back.

Shifting of the times?

A little bit. When I grew up in the New York City Ballet, Mr. B would not have allowed it. But Allegra Kent had three children, I think, and Karin von Aroldingen had a daughter. It was not impossible, it just was not acceptable for most people.

The white butterfly or Sylph. What was that about?

This is my famous Peter Martin story. Melissa Podcasy and Tamara Hadley were chosen to dance the role, and Ricky was directing. Peter was overseeing it and would come to coach. Ricky said, “I want Debbie to learn the sylph.” Peter was like, “What? No, I just don’t see her as the sylph.” To which Ricky responded, “Well, why not?” Peter said, “Well, quite frankly, I’ve never seen a black sylph before.” The reply was just total Ricky. “Have you ever seen a sylph before?” It was a great story, but it was sad. I know.

Was racial discrimination prevalent, and are there examples?

I once was told I was not admitted into the American Ballet Theater because . . . “I already have one of you” . . . an African American soloist in a Ballet company. Another small example was in Cinderella. I was chosen to play the Ethiopian Princess. In that performance, the Prince goes around, searching for Cinderella. I wore a nude unitard, with bones on my bodice and whatever. I was asked to play a buffoon, roll my eyes and do the blackface basically. “If you want me to do it like that, then get somebody else,” I said. It was Valerie Panov’s version of Cinderella, and he was rehearsing me. When I said that he looked to me and said, “Are you stupid? Or you just don’t get it?” Looking back over my career, my entire nine years with the New York City Ballet, there was never another female black dancer. Mel Thomason was the only male, I believe, in the company with me.

Is Raleigh, North Carolina a good place for you?

It is, yes. When we first moved here, it was a little difficult because the downtown did not exist. We came from Miami which was booming. We moved here when my youngest daughter was 18 months, and my oldest daughter was in first grade. It was a great place to raise children and schooling was really good. Miami is a great place for young people, but to raise children, it is harder, and private schools are a must. Here, you can send your child to public school. They are going to have a good education.

What is the Carolina Ballet?

It’s a company that was founded 22 years ago by Robert Weiss. It’s now one of the top ten ballet companies in America. Our home is here now, and our life is here.

Being a ballerina requires immense dedication. What does that look like?

Ballet begins at age eight to eighteen years old – usually your growth spurt. It takes 10 years to really become a dancer. It takes as long to become a doctor as it does a dancer. 12 hours a day for 10 years . . . and then you are 18-20 years old.

What happens next?

Hopefully, you get a job in a ballet company.

ELYSIAN Publisher, Karen Floyd, with Debra at The Carolina School of Ballet in Raleigh, NC, where they recorded Debra’s Inspiring Woman interview.

How many women are in a ballet company typically?

Well, it depends on the company because the New York City Ballet has probably 50 – 60 women.

What is the average salary of a principal?

That also varies. New York City Ballet is in the $3,000 a week range, but we are nowhere near that range.

Racial injustice in the world of ballet . . . what is your reaction?

No one should be marginalized because of their skin color. You should never, never have to experience it. Somebody once said to me, “You got into New York City Ballet because you were black.” I looked at them and said, “Are you crazy? No, no, no way. You know, no one should get in because they are black, and no one should not get in because they are black.”

Is life a big circle of sorts?

Yes, it is. I just taught at the Dance Theatre of Harlem Art School last week too. The director of the school is a man named Robert Garland who is also a dancer and the resident choreographer and director of the school. They had their 50th-year celebration at City Center and invited black ballerinas over the years to attend. Robert called and asked me if I could bring a picture of my mother. He told me he wanted a picture of my mother because when he was first at Julliard, my mother was working at a bank, opened his account and granted him a student loan. Robert said that my mother asked him about Juilliard and what he was studying? When he said he was in the dance department, she said her daughter worked in the New York City Ballet. He asked her for her daughter’s name, and she said, “Debra Austin.” He went, “Oh my God, you’re Debra Austin’s mother?” Every time he went into the bank my mom would ask, “Did you eat? How are you? How is your money? How are you doing?” Every now and then she would give him money to go get a sandwich. He said to me, “She fed me.” Robert hired me to teach for the Dance Theatre of Harlem School summer programs. Not that he would not have done it, but my mother was so kind, it made us cross paths again and made a complete circle.

Will your daughters carry your torch forward, in their own ways?

Yes, hopefully. They will eventually.