Winston Churchill’s granddaughter draws on creative spirit

Edwina Sandys, you are the grandchild of Sir Winston Churchill. Can you tell us about your childhood?

I was born in London in Westminster just before the war started. We lived in the middle of London and, at some point, the house was bombed. We weren’t in it, but my grandfather, Winston Churchill, was Prime Minister at the time.

According to Nanny, who looked after us when my parents were busy, grandpapa sent a military car to pick me and my brother up and carried us to Chequers, which was the country house for the Prime Minister. Grandpapa was said to have come outside to greet us, and he looked at us and said, “Poor little shelter brats.” Anyway, I don’t know if it’s true, but Nanny said it was, and she never lied.

Do you have fond memories of your grandfather?

I do. My grandmother was a wonderful person, Clementine, and I think she kept everything, the whole family life, together. And so, it was the most wonderful place whenever we, all the grandchildren, went to visit grand mama and grandpapa. It might have been at 10 Downing Street, it might have been at Chequers, but it might have been at their own country home, Chartwell, which, of course, particularly grandpapa loved. My grandfather was unlike a lot of men, not only in some of the wonderful ways, but a lot of men who are successful, they go to the office. They do their business. They go over their Law Courts or whatever they do, and then they come home. My grandfather did not. Wherever he was, even when he was at home at the weekends or in the evenings, he did his work. Wherever he was, he would be writing his books or writing his speeches. He brought everything home.

Edwina Sandys (front left) poses with grandfather Winston Churchill (far right) and family at her sister’s christening in 1943.

With even say lunch, or on the weekends, if he was going to meet Field Marshal Montgomery, something like that, he wouldn’t be going and having a separate lunch with him. He would be just in the dining room. If there were children staying, they would be there too. He loved his dog Rufus who would always be around. And he had a budgerigar called Tobi, a green one, that would hop from head to head. He did not say, “Now I’m doing business; I’ll go off with the important men and discuss it.” They would just be doing it at the table. We would be flies on the wall. That was the wonderful thing about growing up with my grandpapa. For his entire life, wherever he was, people were around him. They just came. So, that was, I think, a great thing showing that he was an all-around person. He really was a man for all seasons. He lived life to the fullest, and I think that, at the very moment, whatever was happening, he’d be aware and alert to it. It might be partly because he was in many battles, and you must be very alert. You can’t be just off on your own star or moon. I think, particularly in his paintings, he was in the moment. Obviously, people think painting is a distraction. It’s a nice pleasant thing to do, which it is. But once you start painting, and I know this myself, you’re completely engrossed in it, and therefore, you don’t have any thoughts about whatever you’re worried about or thinking about. After you sit down to the canvas, and you start painting, you’re totally engrossed and absorbed in it and completely alert to what you’re doing. It was a wonderful thing for him, especially if you’re carrying the burden of World War I or II on your shoulders. You, for that moment, when you’re painting, you’re getting a change. They say a change is as good as a holiday.

You have credited your grandmother, his wife, with a lot of the balance in his life. Can you describe her for me?

Yes, she was very beautiful, very strong, self-controlled, and he was lucky because if he’d married the wrong woman, the world would be a different place. She had her own opinions, and sometimes he listened to her. When he was in the First World War, they wrote letters to each other every single day, and many of them have been published in a book. It seems incredible now that if you put something in the mail, it does take one or two days to get there even in this country. It is amazing to think that letters had to get over the Channel from England to France. Their letters were continually sent both ways. So, they had a complete diary through the letters, which wouldn’t have been the case if they’d been at home together. So, I think that they were a team. She did have her own thoughts and was much more cultured than he was, as far as the arts. She had been brought up properly and dabbed with a sort of colony of artists who’d gone away from England to be more free. She did know about painting. I think he mostly got to know about painting once he started actually painting. I think he thought, “Better go to a few museums and see what Michelangelo or Rembrandt did,” and then he looked at that too.

Does your love of the arts stem from your grandparents?

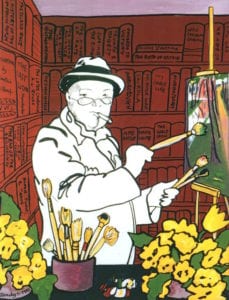

“Winston at Work,” 1991. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 24 inches.

The first artist I ever knew was my grandfather because we didn’t live in a world with artists. The first person I saw painting was grandpapa, and I would stand behind the easel and see him put magic on the canvas. It seemed incredible that somebody could just paint what was out there in the garden or wherever. I always liked drawing at school when I was a child. We always did our own Christmas cards, and we were meant to do homemade gifts also; not just buy something in the shop. So, we always did cards for him and sometimes pictures for him, and he sometimes would give a little bit of advice.

Is it more challenging and more responsibility being a child of Someone of the Greatness of your grandfather?

It is a lot to live up to. I don’t think any of us can quite live up to it, but it’s good to have that beacon ahead of you, to know somebody has done some marvelous things and lived life to the fullest.

You were in politics for a short period of time. How did that happen?

I suppose I wanted to do something more than just be a nice young lady. After I had a couple of children, I thought, “what could I do?” I thought maybe I would go into politics. I became a town counselor in London. But my husband at the time, decided to go into politics, and he was getting a seat, a safe seat, in Cornwall, and he was going to win it. He’d already fought an impossible fight to prove himself. He was chosen in Cornwall. They interviewed 70 people to choose the one, and then there was a short list of three. They only interviewed men with wives, like the vicar and the vicar’s wife. So, you see, they wanted to have a team. We won and got the seat. He was chosen, but then I was also thinking that I would start that same bottom rung of the ladder. So, in London, I got chosen for a seat, which was one that I could not win, but it was going to be interesting. The people in Cornwall told my husband, “Edwina can’t do this.” He said, “Oh why?,” because he was quite reasonable. And they said, “Well, it’s as if to say we’ve got a big event coming on, and we’ve hired the cook and the butler, and now you’re saying this event is happening, like the election, and the cook’s not going to be available.” He was quite decent actually. He said, “You can go on. You know, you will win your seat, but you can go on, and I will probably lose mine. They’ll cancel me.” I felt I could not be responsible for him not having the opportunity to go into Parliament. I didn’t want to be responsible for that, and I wasn’t sure that our marriage would last. So, I went back to the people who had selected me in London. I did not burst into tears, but I felt a bit sad. I felt I’d let them down because they’d chosen me. Anyway, I said I couldn’t do it. I said I have to stand by my man, which I did. He got elected and that was fine; then, we split up later.

Why were you drawn to politics?

Well, I suppose I didn’t know what else to do. Yes, I had two ideas. I wanted to do something more than just be a wife and mother, although that’s quite a lot. But I thought I would have been a good TV anchor. I think I would have liked to interview people, just as you are doing today. That would have been interesting and maybe just slightly stick it to them to get some surprise out of them. I think I’d have been good at that, but I thought, “That’s far too scary.” So, I thought, “Well, better try politics. It’s the family business.” I thought it would be easier.

Have you ever regretted that decision not to pursue politics?

No, because if I had been successful and managed to get into Parliament, I’m afraid I would not have done my homework. I’d have been probably a bit dazzled to be frank. There are all those men in Parliament and hardly any women. I think I may have been more useful, as it turned out, being an artist. I mean, very few people in Parliament really make any difference. I’m not saying I have, but I have opportunities to get some ideas out through art.

Can you tell us about those ideas?

Well, for instance, in 1975 I was thinking, “well, what can I do? What image could I do that would be interesting or important.” I made a sculpture called War and Peace. The UN was having images of a rifle with a rose on the top of it. That sort of image was going around, peace between nations. So, I made this image, “War and Peace,” which is a plane, just a flat silver plane, fighter plane, with a bird cut out as a space, and I called it “War and Peace”. When we had the SALT Agreement, when Gorbachev and Reagan got together, and it seemed like peace would break out, I gave one of the small War and Peace sculptures to Gorbachev and one to Reagan. I thought that was a nice thing to do, and it made a point. I had other ideas about other things.

Like what?

These are not necessary all in order, but yes. Oh, yes. I came to live part-time in New York in the end of the ’70s. I lived near the United Nations, and I had a friend who worked there. He told me that there’s going to be this International Year of the Child coming up. So, he said, “Why don’t you make a sculpture for it?” I said, “Okay. Good. Well, how can we do that?” Anyway, so, I made a sculpture called “Child,” which is a marble sculpture with a man and a woman, very simple, together as one sort of block and inside cut out is the shape of a child. So, this is really where I started to get the idea of using a solid shape and cutting a space through it. The space is not nothing, but nothing is as something as the outer part. So, the child is just a vacuum. It’s just the space. But you notice it, and you read the space. So, that became more or less one of my signature ways of making sculpture and maybe painting too.

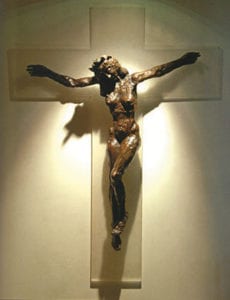

“Christa,” 1975. Bronze on Lucite cross, 4′ x 5′.

Tell me about the Christa.

Oh, God. It’s too much. Well, yes. In 1975, I was working in London doing clay, and I had a studio. I worked in a government studio pacing away. I could go and get clay and everything. One day I was going there, and I thought, “What shall I do?” And I thought, “Yes, I’ll make a female Christ.” See, I like doing things the other way around. Something might have been a man, and it’s a woman. Doing it sort of like that. So, I thought, “I’ll do it.” Then I made the female Christ. I did it very, very quickly and brought a sculpture back to my house, and it was hanging there. My father came in to see me, and he looked at it, and he said, “Oh, Christa.” That’s how I got the name Christa. But I think names are very, very important because it’s like a frame on a picture. It helps the viewer by giving them a bit of a path to knowing. Sometimes they don’t know what to think, and this is a path. Of course, there is nothing to think quite often.

You have different modalities of your expression. I’ve seen everything from acrylic modern paintings, to transformative clay sculptures cast into bronze masterpieces, to marble sculptures and amazing stonework. What is your preference and why?

No preference. All are my babies. The world is my oyster. I think different times. You can’t always do a big marble sculpture, and sometimes you have an idea, and you just do it on a napkin and you have an idea, a drawing. I don’t really think I have to have a preference. My life and my whole stretch of my life are necessarily put into different boxes. People always say, “Oh, you’ve developed so well.” I don’t think I’ve developed in anything because I think some of the beginning pieces of work were as good as the ones I’ve done yesterday.

Part of being an artist in the 21st century requires having to sell.

Yes, I’m afraid so.

Is there any part of that that you like?

I like a sale. I very much like a sale. I really like having a commission. That is a wonderful thing. Knowing a project will be paid allows you to put all your time and effort in. For instance, I did four sculptures for the United Nations. So, although the UN did not pay for the work, people were found to pay for the actual cost of the work. Knowing the work is for something like the Year of the Child or the War and Peace helps give direction. I did a work for the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. To be a special place with a special theme is exciting in a way. It is not just that I wake up one morning and say, “I’m going to do a sculpture with a tree.” I had a puzzle. I had a definite purpose. I was outside myself. There was a place and a purpose. And so, it stretches you in a way you might not stretch just by waking up one morning and thinking I’ll do this or that. So, I very much like having that challenge.

What are you currently working on?

I’m very excited because I am doing a large piece that is going to be outside the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., probably around Labor Day. I have done one a bit similar, but this is the one that they’ve chosen. It’s not going to be permanently there, but it will be there for some time right outside. It’s called Eve’s Apple. It’s a big hand, a right-hand with red fingernails holding a green apple with a bite taken out of it. So, it’s the moment when Eve has taken the bite, and she has the knowledge. She’s thinking, “Perhaps I ought to offer it to Adam as well.” And he’s not — he’s a bit nervous at first, but he takes it. If she hadn’t done that, she would have had knowledge and been in charge of everything, but she offered it to Adam. And because he had superior strength in the days when strength was important, hunting and all that, he got the knowledge too. And so, it’s been a long time for women to get nearly equal to men.

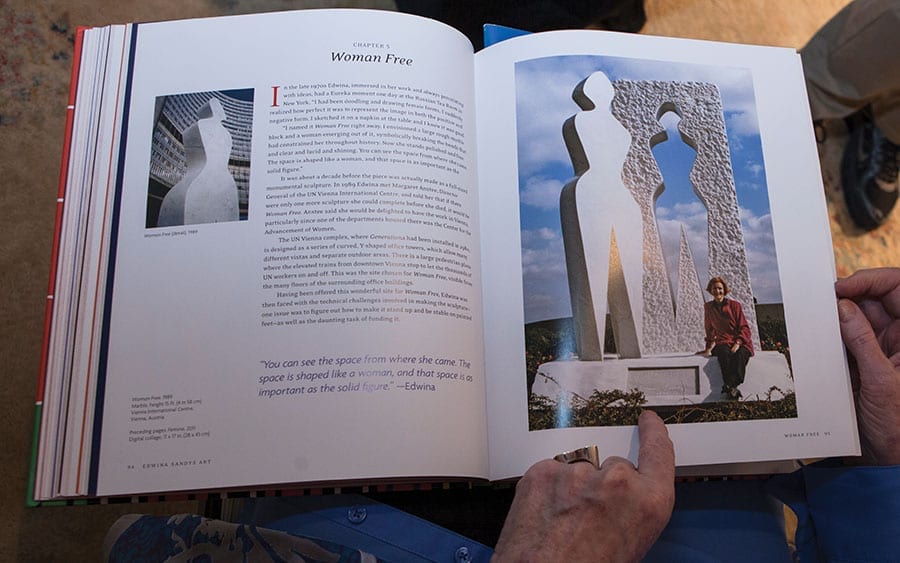

Can you tell us about Woman Free and how is that expressed?

Well, the why is one thing but the how is another. How is it expressed? Many years ago I made a sculpture called “Woman Free”, which went to the United Nations in Vienna. I think that was 1989. And that’s another one of my pieces where the outer part is a rough marble block, 15-foot high, and a woman that the — a silhouette of a woman is cut out, and then that silhouette becomes a polished woman standing free from the main rough block. So, that’s been a theme of mine for a very long time. Or women can be free. Many of them have been partially the years partly by their own bodies, I suppose. And now they can be free, and they can do what they want: be powerful, be themselves, be the best they can be.

Edwina Sandys shows us her book, “Edwina Sandys ART.” This page features “Woman Free,” 1989, marble, 15 feet.

What is next?

So, I would love to tell you, from that sculpture, just this one woman that comes out of the rough block. I’ve now got my dream, which hasn’t been realized yet, of doing the Freedom Circle, which is like Stonehenge and women. The uprights of Stonehenge are like the rough marble blocks which have the womb cut out of them, and then they come free and in the middle. The circle is like Stonehenge, with all those uprights but the women come out. They’re not necessarily in a circle. They can go places. They would be standing around. That’s one that I want to do. I think there may be a chance to put it in Israel. They are very forward looking. It would sit in a big hospital or public place. It would be in a very good place that they will select. The project is in the plans. They still have to get the money, but apart from that, we would create it. But now, and this is something I’ve been thinking about for many years, what I want to do is to take the Wonders of the World, and I want to put them all in the context of women. Now, you see, Stonehenge is one. All right. Then we’re going to have the Pyramid which should probably be the easiest one, though I mean I don’t know how big we’ll make it. I will cut a woman out of one side of the Pyramid. Then we’ve got the Colossus of Rhodes, which is tricky. I’ve thought of a way to make that OK, and then you know Easter Island? They’re huge, huge…they are these huge heads. I want to make them all into women. I won’t need to change very much.

I’m curious about the scale of your future works. Have you figured that out?

Well, the thing for the Freedom Circle is going to be carved like the Stonehenge in Vermont in granite because granite lasts for years if it’s not blown up.

When you create, how much quiet time do you need in contemplation of the creation or is it a reaction?

I don’t really need quiet time in thinking about how to create a work or get ideas. The ideas pop-up usually or develop. But once I have the idea, I need the quiet time to rationalize it or put it into perspective. If I am drawing something, trying out exactly how it would be, that would be taking the more careful time.

What do you consider your greatest accomplishment and why?

Well, my greatest accomplishment, which I could even perhaps further, is being me. So, I think everybody should try to be themselves to the nth degree. You don’t have to be introspective to be authentic. I know that allowing yourself to be yourself, as much as possible, is good. People are often too frightened to be themselves, I think, and try to be too careful. They’re worried always what other people will think. Perhaps it is wise to have a little bit of caution.