The Austrian Immigrant Who Invented the Little Black Dress

IN A CHIC BEAUTY PARLOR just off exclusive Park Avenue in midtown Manhattan, a middle-aged woman sits under the domed bonnet of a stainless-steel hairdryer that’s whooshing air like an asthmatic airplane engine. Her blonde hair is wound around little pink rollers. She is, as the French say, soignée — simply but elegantly dressed in a custom-tailored blue worsted suit. It looks expensive — and is. Draped around her neck is a spectacular, four-strand pearl necklace, The Real Thing, worth a king’s ransom.

“My wonderful husband,” she would demur, “give dem to me. I vare dem, allvess.”

“My wonderful husband,” she would demur, “give dem to me. I vare dem, allvess.”

And oh, what a love affair they had! Three times lucky, she always said. Husband No. 1, dear man, simply faded into the shadows of her dazzling success! Then, the unfortunate rebound marriage that lasted a minute to Husband No. 2! She got it right, though, with Husband No. 3, the handsome Major John Zanft.

She glances at her Cartier wristwatch. She cannot be late. Outside, a stalled line of limousines gridlocks the intersection of Park and East 49th Street, bringing lunch-hour traffic to a standstill. She slips on a pair of eyeglasses with lenses as thick as the bottom of milk bottles, peers out the salon’s picture window, and grins.

“They come. . .for me,” she muses with the expression of a contented cat after dining on an ill-fated mouse.

A crowd has gathered across the street. Though their coats and hats are dusted with snow, communal excitement warms the raw February air. One by one the limousines pull up to the canopied entrance of the world-renowned Hattie Carnegie showroom, where a matched pair of doormen hands out glamorous women wrapped in expensive furs. The crowd goes wild. These women are Hollywood royalty, their idols, who they worship in the tabernacle of their local movie theater in double-feature Saturday matinees, and in fan magazines such as Motion Picture, Modern Screen, and Photoplay.

A woman shrieks over the crowd, “Look, it’s Joan Crawford! Joan-e-e-e!” as the sultry star of Grand Hotel waves to her subjects.

“There’s Joan Bennett!”

“There’s Norma Shearer! She’s fabulous in The Divorcee. They say her husband, that producer, Irving Thalberg, is ill.”

“Ginger Rogers! Isn’t she lovely? She’s got this new movie out with some guy named Fred Astaire . . . not much to look at but can he dance.” The lithe bleached blonde sashays under the burgundy canopy and disappears through glass doors held open by a matched pair of doormen.

All the while, the petite woman in the hair salon across the street has been watching from under the hairdryer. She glances at her wristwatch and snaps her fingers. At once a dainty man with a pencil-thin mustache and dyed, slicked-back, black hair prances over.

“Alex,” she rebukes. “Surely the hair is dry by now!”

“Yes, madam,” Alexandre replies, unrolling a lock. “Voila! She is dry! We shall comb-out tout de suite!”

The woman follows him to the styling chair, pausing to glance out the window once more. The police have arrived to manage the excited crowd. She is satisfied.

Yes, they have come. They have all come to see her today.

Born of humble beginnings

The woman the fashion world would know as Hattie Carnegie was born Henrietta Kanengeiser in 1886 in the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire. She was the first daughter and second of seven children of a poor, soft-spoken Jewish tailor named Isaac and his proud, uncompromising wife called Hannah.

The exact place of Hattie’s birth is uncertain. Long before she established herself as a major player on the world stage of fashion, she claimed glorious Vienna as her birthplace—part of the carefully crafted façade Hattie created to conceal her lowly birth. Upon careful speculation, it is likely she came from the squalid rural outskirts of Leopoldstadt, the northeastern suburb of Vienna known as the Second District, the “Unterer Ward,” or Jewish Ghetto, which was established in the mid-17th century. Encircled by the Danube River, the district was home to various notables, including psychiatrists Sigmund Freud and Viktor Frankl, composers Arnold Schönberg, Johann Strauss I, and Johann Straus II, and Hollywood producer Billy Wilder. With the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1867-1918) after the First World War, the lines of demarcation were drafted and redrafted, so at various times Hattie’s birthplace may have been part of Austria, Poland, Hungary, or even Galicia.

Hattie’s mother could read and write, which was rare for a poor Jewish woman in the mid-1800’s. Hannah believed only education could release her sons and daughters from the bondage of poverty. She scrounged, saved, and stretched every gulden she made, selling homegrown vegetables, home-baked goods—doing whatever she could to augment her husband’s meager income, so their children could attend school. By the time Hattie was 12, she and her oldest sibling Herman, 14, were forced to leave school to help support the family. Herman worked menial labor. Hattie washed dishes and floors. Nonetheless, she had an unquenchable thirst for learning, auditing courses at Columbia University and NYU well into her sixties.

One wintry evening, tragedy struck the family when their modest house burned to the ground. Consumed in the fiery blaze were all their worldly possessions; buried among the ashes was all hope of rebuilding a life in their homeland. But their dreams did not go up in flames. Undaunted, with little more than the clothes on their backs that Isaac had sewn, the family set sail for America, confident of a bright future. Imagine their excitement when they saw the torch of the Statue of Liberty light the night sky!

The family name, Kanengeiser, does not appear in the immigration records at Ellis Island; neither does Kannengiesser, Kannengieber, or Koningeser, other speculated spellings. However, the passenger record of the S.S. Rotterdam, which sailed from Holland and docked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on February 28, 1900, does list a family that fits the description under the name of Kranzer – Hannah’s maiden name. Whatever the case, the original name was lost in translation, probably entered incorrectly or even changed by an inspector in the chaos of processing tens of thousands of immigrants daily through Ellis Island.

Hattie and her family settled in the Austrian-Jewish neighborhood on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Typhus was epidemic in poor neighborhoods, where squalid living conditions, fetid open sewage, and dank winters. The family struggled; all the children were forced to work in deplorable and dangerous conditions.

Three years later, Isaac died from typhoid fever.

Hattie starts a new life in the New World

Inspired by America’s richest man, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish émigré who came to America in 1848 as a boy, Hattie chose Carnegie. After all, she reasoned, why not have a name that is associated with success and wealth? Before her death in 1956, a month shy of her 70th birthday, Hattie Carnegie, the wealthiest businesswoman in America, commented to Time magazine.

“Over forty years ago, my parents brought us to America to give us a better life. I was determined to make them proud.”

Hattie’s early life in New York

Thrown into the hustle-bustle of burgeoning Manhattan, surrounded by new sounds, smells, and sights, the precocious, multilingual teenager (German, French, and Yiddish fluently) quickly mastered English. Determined to make something of herself, Hattie, 13, borrowed a dress that made her look older than her age, gathered up her courage, and walked 30 blocks uptown into the most prestigious department store in New York, R.H. Macy & Company. That giant step from factory to fashion changed her life forever. Never had she seen such a place.

She boldly applied for a job and was hired on the spot when Isadore Straus, a German Jew who, along with his brother, owned “the world’s largest store.” Almost overnight the dynamic, four-foot-nine, blond-haired, blue-eyed ambitious young Henrietta was promoted to salesgirl, then floor model, and rapidly earned a trainee position designing hats in Macy’s renowned millinery department. Then and there she got the nickname “Hattie.” It suited her well and despite her mother’s vociferous objections, it stuck. It was an inappropriate name for a carefully raised young Jewish woman. Her mother would always call her Henrietta—but soon, quite soon, the world would call her Hattie.

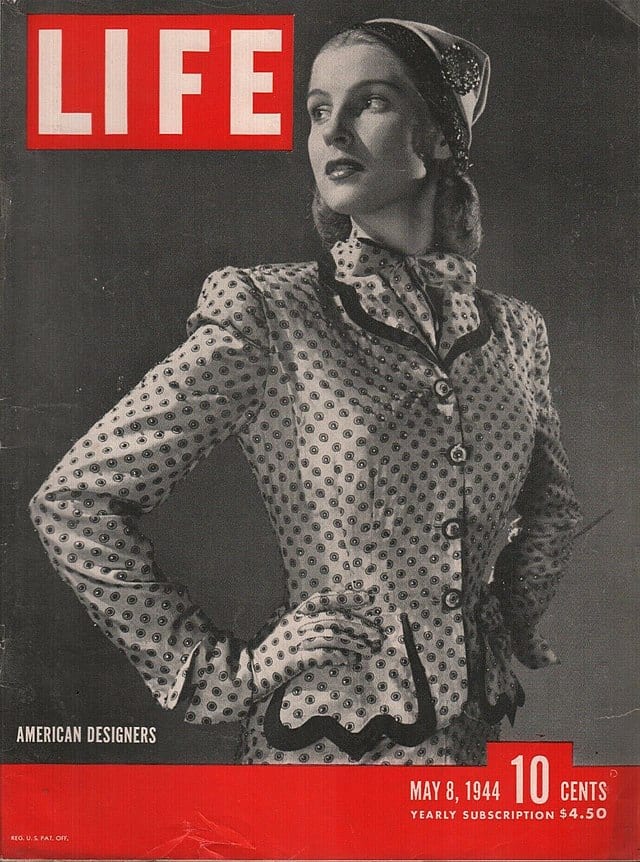

Hattie—and the world of fashion—comes of age

The coming of age of Hattie Carnegie coincided with the coming of age of the international world of couture fashion—and the times couldn’t have been better for the radical change women would experience. Fashion was the outward sign of change—reflecting the new freedom of equality for women—in politics, at home, and in society. The Suffragette Movement was gaining momentum and for the first time in history, women were gaining recognition for their opinions. It was a hard pill to swallow for the conventional male; a play on the old adage, “children should be seen and not heard” applied to many marriages as, “women should be seen, admired and not heard much.” But that’s not how it was at R. H. Macy’s & Company. Isadore and Nathan Straus supported women’s rights. In fact, Macy’s became the first department store in history to offer managerial positions to women and competitive wages. Swept up by this newfound independence, freed from the shackles of her strict upbringing, Hattie gave all she had to her job—and the Straus brothers took notice. But even her rapid rise at Macy’s couldn’t keep her down and she would strike out on her own to launch her own business. She left Macy’s with an affection for her employers that stayed with her and a decade after she was given her first chance by the Straus brothers, Hattie—and the world—mourned the death of Isadore and his wife, Ida, who lost their lives with 1,515 others on April 15, 1912, onboard the ill-fated RMS Titanic.

After Mr. Straus’ death, Hattie felt she had learned all there was to learn at Macy’s hat department and set out to conquer the world. She opened her first boutique, then another, and now this—the glamourous Hattie Carnegie Showroom just of Fifth Avenue—and to this present moment.

Drama Unfolds at the Spring Collection

The crowd parted like the River Jordan for the Lord as she entered her grand salon and mounted the few steps to the chiffon-draped stage. The applause was deafening, drowning out her brief but heartfelt welcome to the many who had come such distances to see her new Spring Collection. And with that, the promenade of models began.

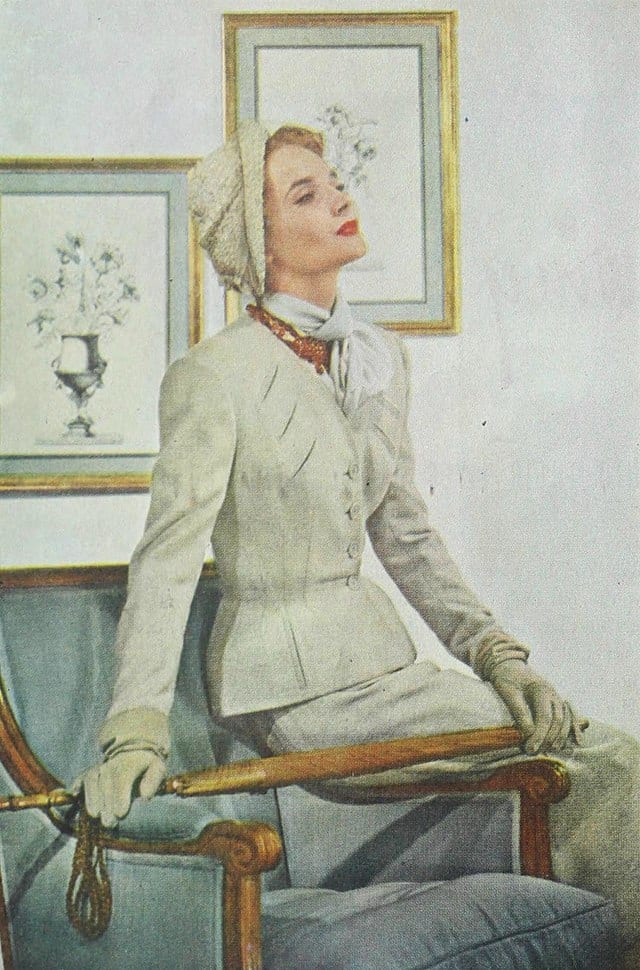

One after the other they came, drifting onstage like a leaf flitting in the breeze: poised, focused, their billowing sleeves and featherweight trains fluttering in the breeze of their graceful walk. One after the other, one at a time…onto the stage each came, pivoted, walked the circumference, and then down the walkway, through the admiring crowd, to a wild burst of appreciative applause.

Thirty models, thirty costumes in all when at last, the final creation, the jewel in the crown, the most spectacular of all: a luscious black satin gown with capped Elizabethan sleeves and a bodice studded with demure black bows. Hattie’s piece d ’resistance was worn by a striking, young auburn-haired model. She appeared to be older than her years. At fifteen, she had left her poor family in upstate Jamestown, New York, and set out for Manhattan, where she was determined to realize her dream—to become a Hattie Carnegie model. That day—oh, how long ago? Almost two years! It was etched in her memory as though it was yesterday. How she had scrimped and saved to buy a one-way ticket to New York, taken a room at the Barbizon Hotel for Women, dressed in her only suit, and walked into the Hattie Carnegie Showroom, trembling, overwhelmed by its magnificence, without an appointment. The coldly critical eye of the receptionist swept over the timid teenager and was about to dash the girl’s hopes and dreams and dismiss her with the wave of an emotionless hand when at that moment, the great Hattie herself walked in—stopped dead in her tracks. Instantly she recognized something special in this striking, auburn-haired girl, hired her, and from that moment on, took the young thing under her wing. Hattie grew fond of the girl, was proud of the girl’s grace, her poise, her hunger to learn and succeed. Hattie knew what it was to be hungry.

And now, to this shining moment. She glided onto the stage for in Hattie’s greatest creation of the season, pivoted like a ballroom dancer, and then, without forewarning, gave out a piercing, heart-stopping scream before crumbling to the floor.

“Let me through!” Hattie commanded as the crowd parted a second time as she made her way from the back of the enormous room. The girl, wailing in terrible agony, looked up at Hattie with terrified eyes.

“I told you we should have gone to the doctor!” Hattie yelled, and with that, the petit, four-foot, six-inch Hattie lifted the five-foot, eight-inch girl into her arms and carried her through the dazed room, out to her waiting limousine, and commanded her driver to make all haste to Hattie’s Park Avenue doctor.

“There is no simple way to say this,” the doctor told Hattie after he had examined the girl and the test results were in. But she has acute rheumatic fever. Hasn’t she complained to you at all? The signs are clear—sore throat, high fever…”

“Of course she has not complained!” Hattie reproached with indignation. “This girl, she does not know how to complain. Three, four weeks ago, I knew she was not well. But no, she insisted! ‘We have the show to do,’ she kept saying.” She turned on the girl. “I should never have listened to you!” Hattie reprimanded her protégé, “but no, you wanted to work, you knew how important…this was to me…you…” And with that, she enfolded the sobbing girl in her arms and they both wept.

When all the test results were in, they could not have been worse. The disease had inflamed her heart, her brain, she could barely bend her elbows or, for that matter, move her weakened body. The doctors feared she would never walk again.

Weeks went by. Hattie had a room made up for the girl at her townhouse. She never left the poor girl’s side. She was there when she underwent the painful treatments, there when was fitted for leg braces and crutches, and there to pay every cent of the medical bills. When nothing more could be done, she took the girl to Grand Central Station, gave her an envelope full of money, and handed her a round-trip ticket with an open return.

“You come back to me when you are well again. Your job will be waiting for you. I will be waiting for you.”

Two years passed. The young girl worked hard and regain her health. The moment she could, she returned to the Hattie Carnegie Salon where her job, and her mentor, were indeed waiting for the nineteen-year-old.

Not long after, an agent for Chestfield Cigarettes came to see Hattie at her office. “We’re looking for a fresh face for our new ad campaign,” he said. “It’s going to be colossal—opportunity of a lifetime for the right girl. You got a girl?” Hattie said she had just the girl.

Then, as if Destiny herself had taken a hand, the great American Broadway impresario, Florenz Ziegfeld, appeared the very next day to visit his dear friend Hattie. “I’m looking for a fresh face, for my new show. It’s going to be colossal—opportunity of a lifetime for the right girl. You got a girl?” Hattie said she had just the girl.

That afternoon, Hattie called the young girl into her office. “You will be leaving me. You have been chosen to be the new Chesterfield girl. And the new Ziegfeld Follies Girl. This is your last day.”

“But Madame,” the young girl cried in a horrified tone. “I can’t leave you! I won’t leave you!”

And then, like a storm cloud darkening the sky, Hattie Carnegie rose angrily from her desk. “You will leave!” she ordered. “You must leave!” The girl wept. Hattie came from around her desk and put a gentle hand on the girl’s shoulder. “My dear,” she said gently. “You listen to me. When a door opens, you walk through. You walk through. You walk through—to your future.”

The young girl became the Chesterfield Girl, the Ziegfeld Girl, and soon after was summoned West, to Hollywood, where she became a Goldwyn Girl. In 1997, twenty years after Hattie’s death, Lucille Ball, then 77 and weakened by her rheumatic heart, wrote in her autobiography that the greatest influence her life, the woman who formed her, and to whom she owed everything, was Hattie Carnegie—who in all but deed, she wrote, “was as dear to me as if she were my own mother.”

This poor emigrant girl became the wealthiest businesswoman in the world. In 1929, her fortune was estimated at over $3.5 million. By the time of her death, she had created a one-woman industry. It was Hattie Carnegie, not Coco Chanel—who created “the little black dress” and the biased-cut dress. It was Hattie Carnegie who invented “ready to wear” and had the first dress shop in a department store, Neiman Marcus, and soon after, Saks Fifth Avenue. Her clients included Joan Crawford, Marlene Dietrich, the Duchess of Windsor and she influenced every major designer in the 20th century, and to this day and was considered the preeminent designer of costume jewelry. Her proudest moment, however, was when she was asked by her adopted country to design the official uniform of the United States Women’s Army Corps, in 1950. And in 1952, Hattie was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor—only in part for her tailored and elegant uniform design. Throughout World War II, Hattie donated every penny of profit from her company to the War effort—and she, herself, volunteered at the Red Cross. And when, at the age of 77, she died in New York City on February 22, 1956, childless, she left her magnificent Red Bank, New Jersey, estate and fortune to become a fully funded retirement home for elderly who otherwise could not afford a good home in their waning years.

We talk about women who inspire. Few have been more inspirational than the poor Austrian immigrant whose courage, vision, and determination changed her world—and ours.