Perfectly coiffed and as elegant in person as photographs have captured, Pulitzer-Prize winner Kathleen Parker rounded the corner of The Washington Post headquarters. The foyer, with high ceilings and an auspicious security detail, shrank in comparison to this enigmatic force of nature. I studied her as she led us to a large conference room surrounded by floor-to-ceiling glass windows on the fourth floor.

Activity by the reporters in the newsroom added to the energy, but there was no mistaking the fact that Kathleen Parker commanded presence.

As if reading my mind, she began talking, preempting a series of thoughts and prepared questions.

Kathleen Parker: When you look at me, you see a person you think probably just stepped out of the Junior League meeting, right? But my life was quite, quite different from that. Very, very different from that. There was violence. There was alcoholism. There were five mothers.

From research, I knew that Kathleen Parker’s mother had died when she was a child. Adopting her direct approach, I asked her how.

Kathleen Parker: She died when I was 3. I was with her. My brother was 6, and we were in the room with her watching television. It was 1954; I’m giving away my age here. We went up to speak to her, and she wasn’t responding. I remember it very clearly as though I were much older. I did everything I could to wake her. I remember pinching her and pulling her hair and crying and carrying on and just being furious with her. I started screaming that someone had killed her, and my brother took me by the shoulders, looked me solemnly in the eyes, and said, “Kathy, nobody killed her. She just died.”

I don’t think I comprehended what that really meant. Then the phone rang. I answered it and told the person asking for my mother, “She’s asleep, and she won’t wake up.”

I know this because they told me later. I don’t know what period of time elapsed, not much, because we were in a small town, but my father and two women, one of whom had been on the phone, came tearing through the front door. I will never forget the expression on my father’s face when he walked in. It was just sheer horror, and his face was — it’s really hard to describe — fallen, I think is the word, but I’ve never forgotten it. It’s tattooed on my brain. I was led by my hand upstairs by one of the women. As I looked back over my shoulder, I saw him pick up my mother. I’m going to start crying. I don’t ever tell this story. He carried her to the sofa — into the living room, put her down and then he just collapsed in sobs on her chest, and that was the last thing I remember for about two years.

Kathleen Parker discusses the importance of family during an interview with ELYSIAN publisher Karen Floyd in The Washington Post newsroom.

I know I was sent away to live with family in South Carolina. My father went away to figure out what he — how he wanted to proceed, whether he wanted to let us be raised by her family or whether he was going to be able to handle two children by himself. He was just 31, as was she. So, it was a big — that was a big moment. And apparently, during those two years I lived with an aunt and uncle in Newberry, South Carolina. I was described by my family as someone who would not allow anyone to help me. I was just completely independent and sort of reserved — coping, I guess. There was no idea then that children needed any sort of conversation about the loss of their mother. In fact, no one in my immediate family ever talked to me about my mother, and there were no pictures of her in our home. I only saw her in the summers when I went to my grandparent’s house, and there was a picture of her in her bridal gown over my grandmother’s desk. So, in my mind, my mother was always a bride, which I sort of extrapolated to mean she was an angel. I think that, in that period of time, when I was trying to figure out, how do you live without your mother? I think I just developed a little attitude. It’s really been the attitude of my life, I think, and it was fine. If that’s the way it’s going to be, fine. I’ll deal.

Childhood trauma often causes adaptive behaviors, so I asked Kathleen whether she experienced fear. Was that her motivation?

Kathleen Parker: Oh, all the time. I mean fear is just a signal. It’s information. So are all emotions. I view them as information. Fear tells me that this is going be something that will reward me in some way, I think. I’m not afraid of fear. Let’s put it that way. Fear is mixed up with all other emotions; excitement, anticipation. Fear like, “Oh my gosh, is something terrible going to happen?” Well, something terrible already happened. I was prepared.

Perhaps Kathleen Parker’s complexity, which one senses immediately, stems from her parents. Her father died 20 years earlier and had been married multiple times. He was as she described, “a serial husband after her mother’s death.” So, I asked, “Was her mother the love of his life?”

Kathleen Parker: Well, I like to think so. I don’t know how things would have gone for them. He was a Yankee pilot, and she was a Southern Belle. Were it not for World War II, they never would have met because they were from different worlds. My father was from a very intellectual world. My mother was from the agrarian South. She is my heart, and he is my brain, though I’m told she was very smart and also very funny. She was also a rebel by virtue of the fact that she left South Carolina — the first in our family to do so since the 1600s — and married a damn Yankee. That took chutzpah.

“Appearances are never what they seem.”

I pushed her further. What led to her success despite her immense tragedies?

Kathleen Parker: I will tell you two things. One is I was born lucky. Really. Two, I decided to be happy. There’s an on/off switch in your brain, and you can decide whether you’re going to be happy or not be happy. I found that switch. I’ll tell you something else that I realized later in life. I was a pretty little girl, and I never knew anything but a smile from other people. That’s huge. People were always kind to me. They were always smiling at me and that did something. It gives you a little happy place to live. I think so much about little children who don’t ever get that, that sort of daily reinforcement.

Kathleen Parker’s Childhood

My main ingredient was my father. I am my father in a dress. He was a lawyer and an intellectual. And even though I had a brother and a sister, my sister left with her mother when she was 6 and I was 12. Another whole heartbreak, there were lots of heartbreaks. I was abandoned over and over and over again by every mother that I embraced and loved. They just kept coming and going and coming and going. The constant was my father. There were other family members, my maternal aunt, and my second mother, whom I called Mom until she died this year. But Daddy was my anchor as well as my warden. And even though he must have been very difficult to be married to — he was a different person with me. I think I was his apprentice. When my brother went off to school, and my sister went away, it was just us two for all but one of my junior high and high school years.

I’d go to my father’s office every afternoon after school activities. His secretary would pick me up, and I’d do my homework in the law firm library. My father would usually come in and give me a short lesson in the law. Then we would drive home together and convene in the kitchen. Popsie, as I called him, would cook, and I would peel potatoes, while perched on a little wooden stool. I still have it. It’s just a normal little hardware-store, wooden stool, and I’d sit there every night.

Popsie and I talked for about two or three hours each night for years. I say that my education took place on that stool. We talked about every subject under the sun. Basically, he lectured, and I took notes. It should surprise no one that I became a journalist. His father was an English professor and also a newspaper columnist. Our home was very much oriented toward books. When I’d ask a question, he’d say, “Go look it up, come back, and tell me what it means.” The only exemption from manual labor was your nose in a book. No TV.

I know he was difficult. He drank too much. I think he was a philanderer. I just know it, and lots of women came after him. They literally circled the house. During his 40s when I was a teenager, all of his buddies gathered at our house, and it was so much fun. There were two journalists in the group, the guy behind orange juice concentrate, and somebody that was associated with Cypress Gardens. There was a radio guy. It was just a fun group of bachelors, and they had a big houseboat that was very decked out and cool. I had a ball. It was a fun time of life for me. We lived on a lake. Everybody water skied. This was Winter Haven where Cypress Gardens was. And so, life was basically a water ski show. My girlfriends would stay with us, and we skied until sundown every single day. So, growing up there was good mixed with the bad. The bad was the upheaval, and eventually, I became a challenge to my father. He had no patience for that. We got along great as long as I was obedient, and I did pretty well with that for a long, long time.

The defining lesson of my childhood was: “Always tell the truth as soon as possible.”

I told one lie, and my father kicked me out of the house for it. The next day, he put me on a train and sent me to live with an aunt and uncle in South Carolina for the remainder of my junior year in high school. I was not a bad kid. I was a class officer. I was an honor roll student. I was the co-captain of the cheerleading squad. Every parent in town was thinking that I was a good girl. But, you know, I lied. There was a reason for the lie, but I lied.

My father was out of town for a court proceeding 60 miles away, and I was home alone. This didn’t happen often, but I was sometimes afraid to be alone because we lived way out in the sticks. There was no one to hear me, and I was lonely. So, I went to a party at a friend’s house, leaving a note for him that I’d gone to buy notebook paper. He got home early enough to check this out, and he just lost it. He knocked me across the room, backhanded me. Pow. I went flying. Wouldn’t even let me use a suitcase. I had to go by the school in the morning, drop off my books, and get on that train. I was matriculated into Dreher High School in Columbia, South Carolina the next day. My brother was in Vietnam. I had a rough year.

However, on the bright side, I had the best teacher of my life, Mr. James Gasque, who was the first person who told me I could write, and it changed my life. It was probably a blessing that I spent that time up there, but it was a very traumatic event.

Anyway, I would joke to you that, yes, I learned a good lesson. I became a much better liar. The truth is, my father was intent on teaching the virtue of honesty if unsubtlety. He said I can take any bad news, but I cannot take a lie. I always knew that. It was drummed into me that the truth is the most important thing in life. It’s the essence of character and of being an honest broker in life. I guess I learned something from it. Saying what’s true is sort of a compulsion, even if it will hurt me.

Pulitzer Prize Winner Kathleen Parker: “Prizes don’t matter unless you win.”

Considered the most prestigious award in U.S. journalism, the Pulitzer Prize originated in 1904, Joseph Pulitzer, a skilled newspaper publisher and advocate for journalism, established the Pulitzer Prize in his will as an incentive for excellence in journalism. Originally, Pulitzer designated 14 awards to be given out in the fields of journalism, letter, drama, education, and traveling scholarships. However, the Pulitzer Prize Board added the categories of photography, poetry, and music, bringing the total of awards to 21. Kathleen Parker, while at “The Washington Post,” won the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in 2010. Her columns, which she started writing in 1987, became syndicated in 1995 and featured commentary on a variety of social and political issues.

I asked Kathleen Parker whether she was surprised to win the Pulitzer and whether it was a career changer.

Kathleen Parker: Oh, gosh, yes. I don’t think I knew I’d been entered, but maybe I did. Fred Hiatt, who is The Washington Post’s editorial page editor, picked a body of work, 12 columns, and he wrote a letter, which was a masterpiece. I think the letter won the Pulitzer actually. So yes, I didn’t even know anything about it. I was doing “Meet the Press” on Sunday morning the day before they were announced. Another guest said, “Congratulations.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, I shouldn’t have spoken I suppose, but I heard you won.” I said, “Won what? Please say it’s the lottery.” No sooner did I get home than the phone rang, and it was Fred. He’s saying, “I want to give you a heads-up that you won the Pulitzer.” In a lot of ways, it was a career changer. You have a year of walking on air. I mean it was a thrill. I’ve always said prizes don’t matter unless you win. There are a lot of brilliant and talented people out there, and somehow, the world — the wheel turns and lands on your name.

I had been curious about Kathleen Parker’s unique core strength which led to her taking exceptionally controversial stands on issues. As a conservative columnist, her commentary on Sarah Palin and more recently President Trump caused a firestorm. I asked her how she decided to take the positions she took and whether there ever was a risk analysis?

Kathleen Parker: Well, the risk analysis is interesting because there are a lot of calculations that go into what you decide to write about and whether the subject will be interesting to people. I decide first, “What am I passionate about?” With Sarah, whom I’ve met, I first came out of the gate being excited. I loved the fact that she didn’t fit the usual template. All my life, I have hated that women had to be a certain way and that they had to believe a certain thing.

When I first started writing my column, I was considered a heretic in the newsroom because I said something outrageous like, “Children need a father.” I was well aware of what I said because I was a single mother at the time. It was obvious, but nobody wanted to hear that in those days. This was 1987, and it was considered against sisterhood to say such a thing.

You have to understand, too, that I’ve never realized that I was a girl until relatively recently. I knew it when the baby was growing, but, basically, I was raised by a man in a man’s world. I was raised to think like a man. I’m extremely logical, which is not to say women aren’t also logical, obviously, but I’m sort of uber-logical. To me, there was nothing logical about these feminist assumptions and these templates, even to the exclusion of other women.

The fact that Sarah Palin was sort of a cute, flirty girl — which, we from the South, can tolerate — didn’t bother me. When she gave that speech (at the Republican National Convention in 2008), I thought, “That’s fantastic. Look at her. How adorable is this woman?”

And I knew it would tick off everybody who self-identified as a feminist. Even though, of course, I live a feminist life. I just don’t need to carry a flag. That changed at a certain point. We can talk about that maybe. But, nonetheless, when she got to the third interview with Katie Couric, I realized this girl doesn’t know anything.

I mean, I understand Sarah Palin.

She was a good athlete. She was pretty. She could do anything. She was successful in high school. She was successful in Wasilla. She was elected governor. But those things do not translate to the world that she was catapulted into. She wasn’t prepared, and she embarrassed me. As a woman, she embarrassed me.

I always compared her to Shannon Faulkner who wanted to be the first female Citadel cadet. Dammit, if you’re going to be the person who represents women in the military have the discipline to get yourself in shape. She couldn’t do a push-up, and it irritated me. Don’t put the world through your drama if you’re not going to make yourself ready for the job.

Interview footage with Kathleen Parker now available.

Kathleen Parker and the Palin / Trump Backlash

I had no idea there would be the Palin/Trump backlash. Because, you know what? I’ve been saying what I think all those years. All those years. It was just one more column for me. It wasn’t what I said. It was where it ran. This column ran in “National Review,” which was just one subscriber among several hundred. But because it played there, lots of people out there assumed this conservative magazine had come out against Sarah Palin. They didn’t come out against Sarah Palin. They were catching her little starbursts, and they dropped me.

They were furious because they got so much flack. I got 20,000 emails in response to that column. Most of them were not very nice. I lost speaking engagements. I lost friends. I did. I lost friends. That was painful. But I’ve never felt so liberated in my life. It let me out of this cage of compulsory conservatism that I’d been locked in for so long. The problem with this business is that you have to be labeled something. You have to be left or right. I was labeled a conservative columnist when I got syndicated in 1995 by Tribune.

The reason I was labeled conservative is because I said these outrageous things like “Children need a father.” I challenged everything about feminism that I felt irrational, unreasonable or unfair. So, fairness is a big thing with me. I’m a Libra and middle child. What choice do I have?

The bottom line is, I’m always going to tell the truth, and I don’t care about the consequences.

I can’t care. I didn’t anticipate at all that there would be such a strong backlash. At the same time, I heard from people who said, “Thank God somebody said something.” They weren’t on the other side of the political aisle necessarily. I had a meeting at the White House shortly after the column ran, a few days after, and when I was greeted at the door, I said, “Gosh, are you-all still speaking to me?” And the woman said, “Are you kidding? We’ve all been saying that.” Well, here’s what I knew. Everybody was saying (privately) that Palin was out of her league, which is why I decided to go ahead and write it.

Where does Kathleen Parker get her courage?

Kathleen Parker: I think we all wonder where our courage comes from when we have it, don’t we? What’s the source of it? There’s a part of me that’s a little bit of a risk taker; I’m a little bit attracted to risk. Throughout my life, I have to say, I’ve never found anything that made me say, “Oh, I shouldn’t do this.” Even when I shouldn’t, I would still do things. I would do risky things, and maybe that’s just part of it. There are people who will climb Mount Everest. Is that courage — or is that just somebody who is willing to find out what’s there? I was blessed — or cursed — with insatiable curiosity.

There’s a duty attached to this question as well. I feel sometimes that I have to say things, because there’s a chance that nobody will say what needs to be said. It’s funny. I remember growing up now. My friends would say, “Kathy always says what people are thinking and would never dare say.” So, I guess that’s a personality trait of mine.

Kathleen Parker’s Stance on President Trump

As for my position with the current president, I think I came out of the gate right away. I will tell you this. I made a conscious decision at a certain point. It was early. I made a conscious decision because I thought it was my moral duty, and I still consider it my moral duty, to bring this presidency to an end as soon as possible. I imagine that Donald Trump and I would be great friends if we were meeting socially. I would love to sit next to him at a dinner party. He sounds like a fun, interesting, crazy guy — a wild and crazy guy. But I never thought he was of the right temperament, an apprehension that has been proved valid repeatedly. The things that I find objectionable about him are not necessarily that he wants to reform immigration or that he wants to make sure the world understands that we’re not going to just keep drawing lines in the sand that mean nothing.

The fundamental principles of what he espouses are not necessarily objectionable to me. However, the way he says them: the clear fact of his tendency to just fire off, his thin skin, his many psychological issues. I feel these are terrtibly dangerous times. It worries me that Donald Trump may make them even more dangerous.

Kathleen Parker: “I would not be where I am, who I am, without my husband, Woody.”

Prior to her marriage to Sherwood (Woody) MsKissick Cleveland, Kathleen Parker had been married. When I asked her to tell me about marriage, she chuckled and said, “Oh, let’s not.” I probed, and she answered in her matter of fact way.

Kathleen Parker: Well, I never wanted to get married, obviously. Why would anybody want to get married? I never wanted to have children because somebody had told me how that happens and that was just not for me. No, here’s what happened. After my divorce, I was not in the mood to even talk to a man — really ever, ever. I was in my mid-30s now. I knew what I was doing, and I was not interested. I had moved up to North Carolina.

My dad had a little cabin up there, and I was staying there for a while, just catching my breath and spending time with my little guy, who was just 22 months when bio-dad and I split. Then, I met this man — this marvelous man. I had come down the mountain to see my aunt and visit my cousin, who said, “Come have hamburgers tonight. You can finally meet Woody Cleveland.”

She said, “Finally” because, eight or so years earlier, I had met a friend of my cousin’s, who said, “Oh, my gosh, you’ve got to meet Woody Cleveland. He’s getting a divorce. You’re perfect.” Life went along, and I moved to California. Here we are full circle back to South Carolina.

South Carolina was always my retreat, my heartland, my coming home. It was the land of unconditional love. So, naturally I would meet my future husband there. He was just this rock solid, grounded, normal guy. He’s a lawyer. So, of course, I married the good daddy, and he’s kind. I’ve never heard the man raise a voice. He would never raise a hand. That was important to me, bringing my little boy to another family arrangement. We’ve been married 28 years, by the way, and we’ve lived somewhat apart for almost 13 years. There are a lot of ways to be married. I stayed home initially; he had two boys when I married him, so we had boys ages four, ten, and sixteen. There was a lot going on. They stayed with their mom in Charleston, but we had them every other weekend and long periods in-between. So, I was Martha Stewart. I was a short order cook, a master gardener, a chauffeur. I did it all. And, unbeknownst to most people in Columbia, I had my column — a separate, private yet public life. My legal and married name isn’t Parker, so I kept myself to myself to some extent. And I wrote for the most part alone in a garage for several years, earning $75 per column.

I’ve been self-employed all this time, pretty much, except for the CNN gig. So, when the youngest went to college, that being my son who’s now 32, I said, “Woody, I’d really like to go to Washington and do my career the way I always thought I would before I took time out to raise these ungrateful children.” He said, “I completely understand, and I support you 100 percent.”

So, I hooked a U-Haul trailer to the back of my car. I put a sleeper sofa in the back, a table, a chair, and a TV set, and I drove to Washington. I knew one person, and I rented an apartment, sight unseen, a studio apartment. I was 52 and on my way. I’m never happier than when I’ve got a full tank of gas and an open road. So, I got here whatever year that was, 13 years ago. I’m 65 now. In-between, you know, I go back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, as needed.

I asked Kathleen Parker how she and Woody make their unconventional marriage work.

Kathleen Parker: I have a big blue ostrich egg in my D.C. apartment. It’s a symbol and a reminder for me. Woody and I consider our marriage and our family as the egg. Everything we do is always in support of the egg. If the egg is ever endangered, we do something different, right?

The egg is the whole. It’s the unit. It’s the family. We’re just committed to that 100 percent. There’s no question that I would not be where I am, who I am, without Woody.

Would he say that?

Kathleen Parker: Oh, heaven’s no. He’s 1,000 percent humble. Here’s an example. He grew up playing tennis, and he was a tennis star. He won the state championship in singles and the Southeastern in doubles. Back then, they played with little wooden rackets. Woody’s a little bit older than I am, and he has the manners of a Southern gentleman, which he is. The reason I bring up the tennis is because, if somebody questions a ball, he’ll always say, you take it. You take the point. Makes me so mad. I would fight over that point. Not Woody. He is there in his whites, and he just says, “No, no, you take it. You take it.”

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com.

Kathleen Parker: The Injury that Made Her Stronger

“The last thing I remember saying is, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to die.'”

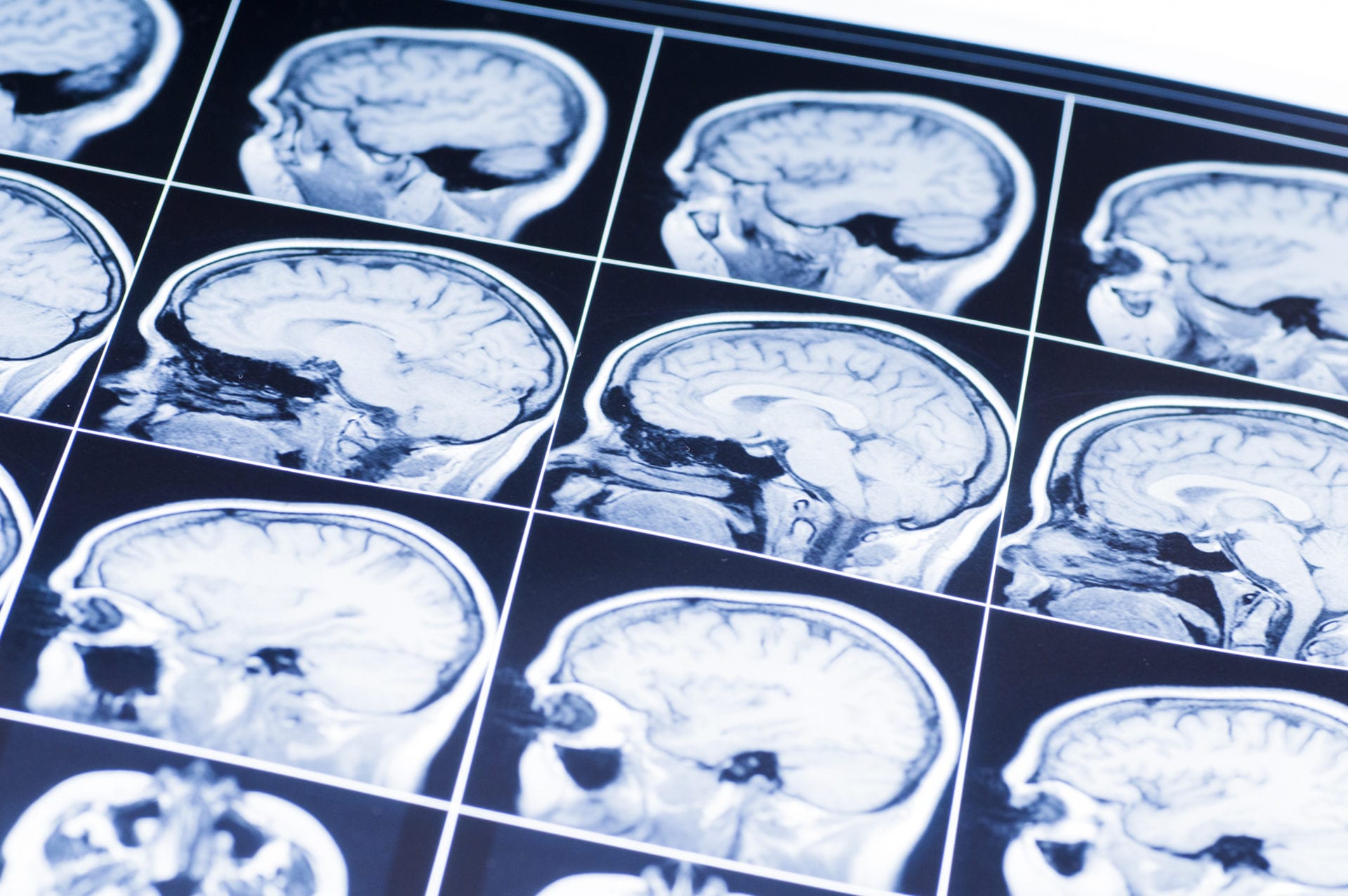

Someone sustains a traumatic brain injury every 13 seconds in the United States; this can be a jolt, bump or blow to the head. Falls account for 47 percent of all traumatic brain injuries (TBI). On average, there are 2.5 million emergency room visits annually relating to TBI.

Currently, there are 5.3 million Americans living with a traumatic brain injury. TBIs cause 30 percent of all injury deaths in the United States. One type of traumatic brain injury is a concussion, which occurs when your brain essentially crashes into your skull due to a hard hit. Symptoms range from memory loss to nausea to an increase in anxiety. Effects of traumatic brain injuries can last for a short period of time or cause life-long symptoms. Recovery is a long difficult process, not only physically, but emotionally as well.

Kathleen Parker: My concussion happened May 22, 2014. I had just finished doing Andrea Mitchell’s show at noon, and the elevator in the NBC building was not working. The building was constructed in 1957, and I think the stairs are approximately that vintage. I had to take the stairs. I was wearing little Princess heels, so, no big deal. But the stairs are very steep and very slippery. As soon as I put my foot down to take the first step, my right leg shot out. It wasn’t even on the first step. It was on the landing. The last thing I remember was saying, “Oh, my God, I’m going to die.” I knew there was no way I was going to survive whatever was going to happen next. You know how time suspends when you’re falling? There was no tunnel of light. It was just sheer terror. I don’t remember what happened, but when I came to, the first thing I did was pull down my skirt. Isn’t that funny? Got to pull down the skirt.

Next, Chris Cilliza, who’d been on the show with me, comes down the stairs — everybody had to take the steps — and he picks me up, and says, “Let me help you up.” I was deposited in the green room with what felt like a swarm of bees. All these people had frozen peas and bandages and all kinds of things. This arm was all bloody, and I was pretty beaten up, but I was in shock. They kept me there for about 30 minutes talking and I finally said, “I’m fine, fine, fine. Let me just go. I’m just fine. Don’t worry. I’m fine, fine, fine.” And this one girl says, “Are you sure you’re fine?” I said, “I just want to go home and cry.” She says, “I know just what you mean.”

Well, guess what? They let me walk out of the building. I went down three flights of stairs by myself, barefoot, and got in the car that they sent to pick me up. I had planned to go to the Eastern Shore (after the show) because I had rented a house out there (Oxford, Md.) for a year, and I was going to go spend a long weekend. This was a Thursday. Somehow, it took me two and a half hours to get there. I drove myself. I just got my dog and put him in the car, and I drove. Usually, it takes me an hour and 20 minutes. I don’t know where I was all that time. I got to my house, and I went to bed. Everything was fine, I thought. I was just oblivious.

How Friendship Helped Kathleen Parker

The next morning, I am sitting on the front porch when my friend and neighbor, Barbara Paca, rides past on her bike on her way to work. She’s an art historian and a world-renowned landscape architect. When she sees me, she jumps off her bike and comes up on the porch to bring me some fresh greens.

After a minute or two, she says, “What’s wrong with you?” I say, “Nothing. I’m fine. Hi. Nothing.” She says, “No, wait, wait. There’s something wrong with you.” And I say, “No, I’m fine.” She says, “What happened to your toe?” (Because this toe was big and black.) “What’s wrong with your arm?” This thing was a mess (pointing to her left forearm). I say, “Oh, yeah, I fell yesterday. I guess I must have broken my toe, huh?” And she says, “We’re going to the hospital right now.”

I put up a big argument. I say, “No, no, no, we’re not going to the hospital. I’m fine, I’m fine, and I’m fine.” Anyway, I end up going to the hospital, and I tell the doctor, “I’m fine.” He asks me a bunch questions, takes an X-ray and pronounces that I have a concussion.

Barbara, who has a child with cerebral palsy and lives in the world of neurology, took control over me and my life. I don’t know what would have happened to me without her. Barbara took me to all of my doctor’s appointments. She was my advocate with the neurologist. She fed me every day. I mean, either brought me food or Jorge would deliver a tray of food. She would bring me a fresh juice in the morning. And then, on alternate nights, she would have me over for dinner with her and friends. I became very aware that I was not right; I kept trying to write my column. On week three, I called my editor in tears, and I said, “I’ve been writing for nine hours, and I can’t make any sense of anything.”

Fortunately, he understood better than me. He had a child who’d been hit with a lacrosse stick and had to be homeschooled for a year, and he said, “Kathleen, you must stop. There’s nothing you can do but rest and wait for your brain to heal.”

So, let me just sum it up for you. It took me about five months before I was able to think about writing again. During what they call post-concussive syndrome, I couldn’t stand any stimulation: no light, no TV, no computer, and no sound. I wanted no one around me. I couldn’t even walk down the street because just the passage of the landscape was such overwhelming stimulation. Everything was just too much data. Everything. So, I sat in a chair, intermittently getting in my car and driving myself to a variety of treatments that I more or less engineered myself. I would sleep for 13 hours a night and then take a three-hour, four-hour nap in the middle of the day.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com.

Kathleen Parker on Head Aches and Therapy

My head hurt for weeks and weeks and weeks. I was seeing a neurologist who had sent me to physical therapy, who sent me to occupational therapy, who sent me to speech pathology. My speech was messed up. I had a little aphasia, you know, saying weird things. My frontal lobe was affected which meant that my executive functioning was off. My inhibitory powers were not working. They were impaired. That’s the word. I had no incentive, initiative, motivation, all of those things. My homework with my speech therapist consisted of just going across the page and circling the A’s, the letter A. Of course, I wanted to go A, A, A, A, A, zipping around the page, and she said, “No, you have to go straight across.” She gave me crossword puzzles with four clues. I always have done crossword puzzles in ink. Anyway, I don’t know how, but eventually, I started getting better.

Most of my therapy and recovery was a hodge podge of this and that, directed entirely by me. Somebody said, “I think acupuncture would help you.” I said, “Fine.” I’d never done acupuncture. I did acupuncture. Someone else would say, “I think craniosacral manipulation would be good.” Okay. Fine. I’ll do that. I mean, I just did everything you can do.

I had to keep a journal as part of my therapy. I’ve yet to read it. I had little sticky notes everywhere, everywhere, everywhere to tell me what to do: brush your teeth, go downstairs, make coffee, take dog out, close door. Everything. And I had a calendar broken down into quarter hours. I gained a ton of weight because all I did was eat ice cream. Oxford is home to one of the greatest creameries in the United States. I could walk there. I lost all interest in hygiene. I would maybe take a shower once a week. I’m walking around and walking up to strangers and telling them everything. I am a private person, but I guess I felt I needed to tell them what had happened so that I didn’t seem stupid.

Kathleen Parker’s Push to Help People With Concussions

Nobody can tell you anything about concussions. That’s why I want to write a book because I want people to see that there is hope.

Everyone needs someone to say, “Look, I’ve had a concussion, read this book because you can’t explain it.” Of course, if you’re concussed, you can’t read the book, but your friends and family can and that’s important.

Following her concussion, Kathleen Parker knew that she would like to help others who have struggled after injury.

My husband, who was going back and forth between South Carolina and Maryland, would say, “You look fine.” But I wasn’t fine. The thing is, you don’t look different when you have a concussion, so people don’t realize how off you are, which is probably a good thing in social settings but not helpful when you need someone to understand what you’re going through. I learned to read peoples’ expressions. And if people were smiling, I would smile. If they were laughing, I’d go ha, ha, ha, ha. I had no idea what was going on. I would say inappropriate things. I remember some people gave me a dinner party welcoming me to the community. I’m telling a story, and then I’m noticing the faces around the table, and I realize I should not be telling this story. This is not going to end well, and I don’t know how to stop.

I knew, without question, that I would never go back to being who I was. Kathleen Parker had died. I was clear on that. I felt bad for her. I was sad for her, but I would not be able to go back to being her. I emphatically didn’t want to. Politics was, in stark relief, an absurd waste of human time and potential. I knew that with an acuity I’d never experienced before. As I got “more well,” of course, this feeling began to fade, and I had to make a living. Even so, I trust what that other person had figured out.

Another side effect of my injury was a tsunami of empathy. It was so overwhelming, and I felt, “Oh, my gosh, what happens to people who don’t have the resources I have? Who don’t have the boss who understands concussion? Who doesn’t work for the company that will pay you even while you’re sick?” I couldn’t stand any of that. It was just — again, it’s that fairness thing. So, the joke is: I had a brain injury and became a Democrat. But my concussion was a revelation upon revelation upon revelation.

I want to help people with concussions. I really do because it is horrifying. It is so scary. It is so scary. You don’t even know who you are. So, one day somebody asked me, I’d forgotten this when you asked me earlier, “What inspires you?” I should have thought of this. Somebody asked me, “You’re always in a good mood. Why are you always in such a good mood?” And I said, “Because every single day I wake up, I know who I am, and nothing is wrong after that.” You know, I just can’t ever, ever feel sorry for myself, wishing things were different. To get my mind back, it’s not just your brain, it’s your identity. It’s who you are. It’s everything. People lose that every day in this country. And nobody knows how to talk to them or how to deal with it.

I love all the people who helped me, by the way. They were my support. They were my family. They were my friends. I once asked my speech therapist, “There has to be something good about concussions. I can’t write anymore. Maybe I can paint or sing.” And she said, “No, there is nothing good about concussions.” That was like telling me I couldn’t get better. I just decided that was not going to work for me. I clawed my way back, and it was really rough. But every day got a little better. And here we are.