KRISTIN HARMEL was born to write. At the young age of 16, she had already landed her first major gig as a sportswriter covering Major League Baseball and NHL hockey. Since then, her career has flourished, as she has covered an impressive variety of topics for major publications and networks, including PEOPLE magazine, Travel + Leisure, Glamour and The Daily Buzz. Kristin’s passion for journalism carried her far, but what she truly desired was to become a novelist. In Paris, on a break from PEOPLE, she wrote her very first novel while still in her 20s. Today, she is a New York Times bestselling, USA Today bestselling, and #1 international bestselling author, as well as the co-founder and co-host of the weekly web show and podcast Friends & Fiction. Enthralling, engaging and evocative are all common words used to describe Kristin’s works, making it clear to see why these page-turning novels are sold all over the world.

Did you always know that you had a gift for writing?

I like to joke that I have never wanted to be anything other than a writer, except for two brief periods, one of which was when I was three years old. I would tell anybody who would listen that I wanted to pump gas during the day and play the piano in a bar at night. I have no idea where that thought came from or how it entered a little three-year-old’s imagination. When I was nine or 10, I was convinced I was going to be a pop star. My name was going to be Mystica. But sadly, the complete lack of singing ability stood in the way of that dream. Aside from that, I’ve never wanted to be anything else. I have been making up stories for as long as I can remember. My mother found my first “book,” which was a stapled together Bobbsey Twins tale that I wrote when I was six. Writing has always been my dream.

Do your ideas and stories “percolate” or “explode” onto the page?

Probably a combination of the two because I outline extensively. During the outline process, stories just come onto the page. I don’t stop and take the time to filter the ideas or worry about the shape they land on the page. When I write my first draft, it tends to be that way too, because I use the outline as a guide. This process frees up that self-censorship that gets in the way. Sometimes when you are starting from scratch, you ask yourself if the idea is going in the right direction. This process helps.

How did COVID affect you and your writing?

It was difficult. I have a five-year-old, and his school was closed for the first few months of Covid-19. We never were comfortable sending him back, so our schedules were completely changed. I think that was the biggest impact. For me, it also canceled two book tours and cut into my writing day. Before Covid-19, I wrote when my son was in preschool. Once he was no longer at school, I was no longer able to write during that time, which completely rearranged my schedule. I wound up working early mornings and weekends, which impacted my husband and me. We became ships passing in the night, trading off our son and not really spending much quality time together. I am looking forward to getting back to a more normal routine.

How many books have you written?

It depends how you count them. This is my 13th full length novel under my own name. Fourteen, if you count novellas. Sixteen, if you count books I have written under pseudonyms.

Did you ever ghostwrite for anyone?

I did. I was a ghostwriter for Chubby Checker’s autobiography. He was born in South Carolina and grew up in Philadelphia.

The book has not been published because he is not ready to do anything with it yet. But we worked together on it for years. I never set out to be a ghostwriter. It was a project I just fell into. We wound up meeting at a time when he was looking for a ghostwriter, and it has been one of the most wonderful experiences. He has become one of my dearest friends. He is Uncle Chubby to my son. When my husband proposed, he asked my mother, father and Chubby for their permission first. It has been a wonderful experience that has shaped my life.

You have also written for multiple magazines. Tell me about writing for People Magazine.

I always wanted to write novels. I felt that was an unrealistic career goal at age eighteen, right out of the gate, so I decided in the meantime I would go into journalism because I could use and develop my writing skills. It would also give me the chance to talk to people, which is what I loved and still love about journalism. It’s the idea that you can ask people questions that you would not normally ask someone you just met 15 minutes earlier, right? You can ask me about what makes me tick or what did my mother and father do, personal things that don’t normally come up in conversation.

I also loved the ability to get inside people’s heads. I started querying magazines when I was 16, cleverly omitting my age from the query letter. So, I wasn’t lying, but it just seemed like there was no reason to share that. I landed my first professional assignment, and I started off as a sportswriter covering Major League Baseball and NHL hockey at 16. I was masquerading as an adult, which is crazy, but I wanted to be a journalist. By the time I went off to college at the University of Florida, I had already amassed magazine clips. I had been published many times over the preceding two years which led me into a couple of internships, one at Woman’s Day when I was 19, and one at People Magazine when I was 20 or 21.

Interning at People Magazine turned into a job that lasted 12 or 13 years. It is foggy when it ended, because I was still doing a little bit of freelance work for them. It was a wonderful experience covering three Super Bowls, going to the NBA all-star game and MTV Movie awards. I interviewed so many people. You would think my all-time favorite story would be a celebrity such as Patrick Dempsey—be still my heart—Ben Affleck, Matthew McConaughey or people like that. But my favorite, honestly, was a man named Henri Landwirth. He was an extraordinary man. He founded an organization called Give Kids the World, which gives critically ill children and their parents a dream vacation.

It is a memory the children and families can always have. The organization brings critically ill children and their families to Disney or Universal or whatever. Henri was a Holocaust survivor, and he spent the years from 13 to 18 in concentration camps. He became an extraordinary American success story. His two best friends in life were Walter Cronkite and John Glenn, both of whom, in separate interviews, said he was the most extraordinary man they had ever met. Talk about high praise from people who have met a million people! He said that during the time he was in the concentration camps, in order to survive, he had to learn to turn his emotions off. And when the war was over, he never knew how to turn them back on again. That statement impacted me so much that it has stayed with me for years. I thought about it again and again, that intangible thing that could be taken away from you, something we take for granted—the ability to love, the ability to hope, the ability to feel any of the emotions that we take for granted. Those emotions had been taken from him. And that, ultimately, became the core of one of my characters in my first World War II novel, that I wrote in 2010 and which came out in 2012. It was a PEOPLE magazine interview that got me thinking about World War II and how much I wanted to delve into it.

And World War II is really your sweet spot.

It is.

How many novels in that genre?

The Sweetness of Forgetting, When We Meet Again, six or seven. There are so many interesting stories from that time period that continue to resonate today and continue to bring us real life lessons. I think it should feel much further in the past than it is. World War II was 75 or 80 years ago, but we can readily identify so much with people living then. Most readers today have a personal connection to somebody who lived through that war, whether it was our parents or our grandparents. It feels very accessible, and there are a lot of messages from that war that we haven’t entirely learned as a society yet.

We also are just at a moment of our modern history where we are beginning to look back and see all the things that women did during that war. Ten years ago, if you had asked somebody, “What do you know about World War II?” they would have told you about the battles staged by men, but there were a lot of women behind the scenes, too, women working for the underground, the resistance and doing other important work that won the war. It is interesting to bring those stories to the forefront and remind people, not just of the women, but of all the people working behind the scenes in everything and how important they are.

In July, you released a new novel The Forest of Vanishing Stars?

In July, you released a new novel The Forest of Vanishing Stars?

Yes, The Forest of Vanishing Stars is the story of a young woman who was kidnapped from her German parents when she was just two years old. On her second birthday, a woman takes her from the family apartment in Berlin, believing she has been called by the forest itself to take this girl and give her a different fate, a different destiny. She takes her deep into the woods and raises her in the wilderness with every survival skill she’ll need; differentiating the nourishing mushrooms from the poisonous ones, the herbs that heal and the herbs that hurt, how to kill a man with her bare hands and how to build a shelter in the winter. She is taught all of the things she needs to know to survive, but has virtually no human contact and, thus, almost no interpersonal skills. After the old woman dies in 1942, the young woman wanders the forest alone following the old woman’s orders to stay away from villages to protect herself. Her life crosses with a family of fleeing Jewish refugees. She finds out for the first time what is happening outside of the safety of her woods. She learns that the Germans have come into Eastern Poland and have begun putting Jewish citizens into ghettos, murdering them, taking them away to their deaths. Jewish people were fleeing into the forest trying to escape that fate. So, she is faced with a choice: do I retreat to the safety of the woods, which is what she had been taught to do, or do I use what I know to help? Obviously, she chooses the latter or there would be no book, right? It would be a very short story if she chose the former. Everything changes for her, and she is basically forced to understand human interaction for the first time.

This is a “coming of age” story, but it’s also a story about identity. How much is she responsible for based on who she was born to be? Or how much was she shaped by this Jewish woman who kidnapped her and raised her? How much has she been shaped by the decisions that she makes? The story is about how our identities are formed too. The novel is based on the real-life stories of Jewish refugees who fled into the forests of Eastern Europe. What is extraordinary is that there were thousands of Jewish refugees who left the ghettos, left the villages when they knew they were going to be put into the ghettos, and found their way to the forest and survived the war against almost impossible and insurmountable odds. Those stories are so inspiring and so relevant. While it can look like fate and destiny have one thing in store for you, you can change that. You can change your fate by taking control of it.

It was an extraordinary story to research, not least of all because I got to speak with one of the refugees from one of the largest and most well-known refugee groups. He was a man named Aron Bielski who was 14 when his parents were taken away and when he had to flee into the woods. He is 94 now. To speak to him about not only what life was like out there, but what he learned from it and how that experience shaped the rest of his life, impacted me deeply. Some of the things he said really stuck with me. “Hardship teaches us life,” he said. I think that’s such an important thing to remember; that we don’t learn from those smooth roads we walk along. We learn from the rocky ones, we learn from the challenges, from the difficult times…which was something he learned in a way most of us can’t really imagine.

It was very hard to put myself in his shoes and imagine witnessing my parents being taken away to their deaths as he did when he was 14, to imagine fleeing into the woods, losing everything that you had taken for granted. And not only that, but his job within the group that he was a part of in the woods, was to go into the ghettos and convince people to leave. He risked his life, time and time again to bring people out, to give them a chance to live. Another quote that stuck with me was so simple, “Be nice if at all possible.” He said that was something he learned during that time and going into the ghettos was an extreme example of that. He was certainly being nice, by giving people a chance to live. It’s amazing to look at this person whose life, as he knew it, was completely stripped away from him at age 14… such a young and formative age. But he survived and 80 years later, he’s still here to talk about it. What a gift.

The protagonist in the novel was in search of her identity, and she faced dueling pasts within her that she doesn’t totally understand. Where did that idea emanate?

I didn’t realize until I was midway through writing this book that I had a family connection to that same general area of the world. I always thought that my dad’s family came from Germany, Austria, Hungary—somewhere more in that region. It turned out they were Polish Jews who came over about 50 years before World War II started. While I knew that my dad’s side of the family was Jewish, I didn’t realize that until I was about 20. I was trying to reconcile the Catholic upbringing I had with the other piece I discovered. It’s a journey I have been on for the past 20 years. Does it shape who I am? Does it make me a different person? Does it give me different responsibilities? I have always been me, but it’s interesting to look at the things that become a part of you, even the things you don’t know about and wonder how they’ve shaped your journey and how they shaped your future. I think in that way, Yonas’ search for identity probably is somewhat reflective of my own journey and my own search for identity.

Did your father tell you stories of his family’s immigration?

I don’t think he knew most of it. My parents divorced when I was 11, a typical time and age probably that I would have been asking those questions. But also, we were not close during those years. Thank goodness for things like Ancestry.com that allow us to look back and see things like census records and immigration documents. I found documents showing that my great-great-grandmother, whose name was Rosie Harmel, traveled back to Europe in 1933. She was 69 years old, got on a ship alone and traveled to Poland. Stumbling across that document impacted me because she was probably visiting people who just six short years later would face the unthinkable. She died in 1941 and must have been horrified to realize what was happening to them, to realize that there was no escape, that they were there in Poland and all these horrible things were happening. She must have certainly lost many members of her family and friends. To know that at the very end of her life, right before she died, this was happening. I had been writing about World War II for a long time, but I never realized that my own family had experienced such a close personal connection to that period.

Do you think intuitively you were drawn to World War II because of your heritage?

Initially, I was drawn to World War II by reading The Diary of Anne Frank, which I read when I was 11 or 12. The first short story I ever submitted to a contest was when I was 13, and it was a short story about a girl in a concentration camp. Something clearly captured my interest, and that story meant something to me.

What was it that resonated with you when Henri Landwirth said he had to “learn to turn his emotions off and never knew how to turn them back on again”?

He lost such a fundamental thing. I think that he lost his ability to feel.

But he obviously felt. You said he dedicated his resources to helping critically ill children. His life was abundantly successful …

But not in the same way that I think you and I do. He had been married five or six times. He wanted to have the “right” feelings to love his wives in the “right way.” And he never could. It was something within him that he just couldn’t access. The reason he founded the organization Give Kids the World, which serves a large number of children who, sadly, may not live to see adulthood, was that these children were having their childhood taken from them in much the same way his was taken from him. Around the children, he felt something. I witnessed something so deep and profound about that loss. I had been so moved by The Diary of Anne Frank and thought so much about losing a parent or losing a sibling, losing all your belongings, losing your dignity.

There was so much loss, but I’d mostly thought about the tangible loss. I don’t think it had fully occurred to me before talking to him that you could lose something intangible that would still shape your life so strongly 65 or 70 years later. But what he lost was so intrinsic to life, so important to the way you would need to live your life going forward, he could never get it back. I have always been interested in the psychological impact of the past on the present, not just the way that the past impacts us, but the way the past impacts the way we raise our children and the way they raised their children. I think that is one of the reasons I tend to tell a lot of dual timeline stories that are set in the past and the present. I like to see how that unfolds through the generations. Talking to him may have set me on that journey or set me back on that path of thinking in more depth about the intangible things that we carry forward, the intangible things that are taken, that we can’t get back. That is what that time period represents.

What do you think life is all about?

A recurring theme in my writing is ordinary people finding the ability to be extraordinary, especially when they are faced with difficult times. I think that when we are faced with difficulty, as a lot of us were during the last year and a half during Covid-19, we find these reservoirs of strength we didn’t know we had. I think that maybe it is about finding ways to survive but also finding ways to be the light in the darkness, even when the darkness isn’t that great, because there will always be periods of darkness in our lives. There are always going to be periods of light in our lives. I think finding the ability to pull your inner strength out and use it to help other people is something that is important as we go through our lives.

Do you think that is why you write?

I think it’s part of the reason I write. Writing has always been a part of me, maybe in ways I can’t explain. I am sure some of it comes from my mother reading to me all the time when I was a child and getting me interested in stories. When we follow where our heart leads us, sometimes those things are hard to explain. I cannot imagine not writing. It would be like not breathing to me because it has become such a part of me. I don’t know how I would define myself without writing. When I had my son, who is five now, I took a few months off from work, and I felt very adrift because it was really the first time in my adult life I wasn’t writing. Because I have this calling or this gift, I have a responsibility, in some ways, to tell stories that can make a difference. I don’t think I sit down and write a book whose purpose is to change lives. But I think that comes through the process because that was what The Diary of Anne Frank taught me. I knew I wanted to be a writer, but up until reading that book, I had read books like the Nancy Drew and Bobbsey Twins series, so I thought books were just meant to entertain you. I didn’t grasp until I read that book that books could change the world through changing how people feel and how people think. I take that very seriously now.

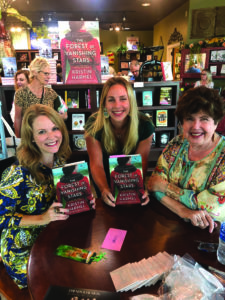

It is the highest compliment that a reader could pay me, that they read something in my book or were impacted by something that shifted their life in some small way or helped get them through a difficult time. I was at a book signing and was asked if I get tired of signing so many books in a row? And I said, “No, I don’t.” How could I ever take for granted the fact that I’m here and there are all these people sitting at a luncheon to see me because I have written something that meant something to them? It is a tremendous gift I don’t ever want to take for granted or lightly.

If you could ask God a question, one question, what would it be?

If you could ask God a question, one question, what would it be?

How can I be better for you? I say my prayers every night, and every time I get into the car to drive. I do have a belief that there is a greater plan that I don’t understand. I write a lot about people from different religious groups working together.

Judaism, to Christianity to Muslim …

Yes, part of that interest probably comes from discovering that I had this whole second religious part to my past that I didn’t know, and then realizing, which I think is an important realization, that at the root of everything, we are all just human, and we all want the same things. I am still Catholic. I believe the things I believe, but that doesn’t mean that a piece of me does not come from that Jewish past too. People are more similar than we think, across religious groups, ethnic groups and racial groups. I believe at the end of the day; we are all just people. I think that is such an important thing to me that finds its way into my writing a lot. So maybe I would ask God if, at the end of the day, we aren’t more similar than different. I believe the answer would be yes, but that we are working towards Him in different ways.

What is in store for you, the second chapter of “your life’s book”?

I would like to continue writing books about World War II. I don’t know if that will always be my journey, but I hope to write books with a similar heart. I will always write books about people finding a way to be that light in the darkness or finding the way to be extraordinary.

What are you afraid of?

With every new book I begin writing I have that deep fear that no matter how many times I’ve done this before, the ability to do it will go out of me. I go through this every single time I begin a new book until I am about halfway into writing it. I spend months thinking, I am terrible at this and am never going to write a book again. I fear failure. I’m scared of not being able to muster that great story…or my career going downhill. I am scared that I have peaked. I am scared of people or bad things happening to people I love. I have a lot of fears about things I can’t control in the world around me and the people I care about.

Do you think that propels you forward, stops you or slows you down?

Fear slows me down because I have always been a person who has a lot of self-doubt. It is something I am working on and is something I think I’m growing out of as I get older. But I still have self-doubt, and fear is just self-doubt in another form. My self-doubt has always held me back. I think I would have started my career writing about World War II earlier if I hadn’t doubted my ability to do it. I think there were a lot of things I would have done earlier in my life if doubt had not held me back. Self-doubt and fear go hand in hand.

After realizing the power of self-doubt, what is the path forward?

Part of the path forward is self-talk, which is a gradual process. With time, getting more comfortable in my own skin is a big part of it. I was not super comfortable in my own skin. Part of the process of maturity and growing up a little bit is realizing that no one is perfect, which is one of the things that I think has really given me a lot of freedom. Truly realizing you can’t make all the people happy all the time is also a path forward. As long as you are doing your best and doing it with kindness, you’re doing what you’re supposed to be doing. If someone doesn’t like my writing, or if someone doesn’t like me, that’s not on me.

Does it hurt you?

Yes. For somebody who has put her work out into the public eye so many times, I do think I have thin skin, but it’s getting thicker as I’ve gotten older. I used to say, particularly earlier in my career, before I was married, when I was still out there dating, all the criticism made it a whole lot easier to date because you get so used to facing rejection. People saying, “I didn’t like this about your book,” was similar to when a date rejected you. Oh, well, I’m used to that, I thought. I do believe that whatever aims to take you down actually builds you up, if you face it the right way. It is developing the ability to face those things head on and to have enough confidence in yourself and knowledge of yourself that they don’t destroy your confidence or take you down. Those are experiences building you into a stronger, better, more mature and more self-confident person. Granted, I am not all the way there yet, but I am working on it.

How do you “pay your blessings forward”?

The biggest thing I consciously do is speak to young people as often as I can, typically high school and college students. Those were periods of my life when I didn’t really believe in myself yet and consequentially, I made bad decisions. There were periods of my life that if I had a little bit more self-confidence and had the foresight to realize that I could build a future for myself, I probably would have done things differently and saved myself a lot of grief. I am often invited to speak to groups of young people about my writing, but I wind up talking to them primarily about how to face the world and how to believe in yourself and how to understand that even though you’re young, you have something to offer. Don’t ever let anyone tell you that you can’t do something. I think that is important. I think sometimes we are moved to pay it forward in ways that would have been beneficial to us when we were at those points in life. There were turning points in my life that could have gone in different ways if I had internalized that kind of advice. So, I like having the opportunity to give that kind of advice to other people.

What constitutes success for you?

For a long time, it was hitting the New York Times Bestseller list. When I did finally hit it, it was great and truly an honor. I can say I am a New York Times bestselling author now, but I don’t know. Maybe it is just the perspective that comes once you’ve reached a goal that you’ve strived to reach for a long time, or maybe it is just a little bit of perspective that comes with age.

Now that I’m back out on the road after Covid-19, having been in my house for a year and a half, I feel differently. People come up and say things to you at book signings. Virtual events are in groups and online and not one-on-one, and it doesn’t feel as personal. In the few days I have been back out on the road, I have talked to someone who said that she read one of my books, and it is what got her through the stillbirth of her child. I talked to somebody who said that she was buying four books because I’m the only author who her family reads across four generations. So, it was for a 13-year-old daughter, a mother, a grandmother, and an 87-year-old great-grandmother. Reading was a way that their family connected. I talked to a woman who mentioned that her father had died just before the Covid-19 lockdown. She was separated from her mother and sisters and that reading one of my books together was one of the first things that got them back to feeling like they were sharing something again, even though they were physically separated.

Those little things from single reader experiences are most important. I was just having a conversation with an author friend, Kristy Woodson Harvey, and I told her the New York Times best-seller list means something. I strive for it. I wanted it, and it is important to me, but that’s not what it’s about. There is nothing that means more to me in my professional life than having someone come up and say something beautiful like that. It makes me realize that something I wrote in my little office in Orlando had an impact on a life at a time that that person needed that impact. That is what success is for me. Being able to be a positive force in somebody else’s life. I know that sounds kind of corny, but I tear up every time somebody says something like that to me. I never want to take that for granted, and I never want to forget that. Therefore, it’s important to keep doing this kind of work.

It is the light in the darkness?

Yeah, exactly. It’s the light in the darkness, very good point.

Pretend that I am your son right now. Give him a piece of advice that would have been important for you to have heard, that could have helped him.

I always did well in school. But my mom was never one who would say, “You got an A plus on your report card; that’s amazing.” She would say, “I’m really proud of you. Good job. But what is more important is that you are kind.” I think a lot of that comes from her. Kindness is what I want to instill in my son. He is smart and about to start kindergarten. He already reads really well, loves books, loves numbers, loves math. I can see he is smart and if he applies himself, I think he will do well. I want him to tap into his potential, but I don’t ever want that to overtake the importance of being a kind person.

I don’t know how his life will go yet. I don’t know how easily school will come to him. I do think that if it comes easily, he might settle into that belief and feel he is better than other people, in some way. And it doesn’t make him better or superior. It just means his gifts are different than somebody else’s. I would tell him to never rely on that, to never let anything other than his kindness define him. Kindness is something that he always has control over and is something that he can use for the rest of his life. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter whether you made an A or a B on a paper, it matters that you were a good person throughout your day. That is what I would tell him. I want him to strive for his version of success, if that is something he wants, but most of all, I just want him to be a good human being.

What inspires you spiritually?

The belief that all through our lives, we are working toward a deeper understanding of God. I think it is the acts of goodness that get us a little bit closer to that understanding.