Olympic Gold Medalist, Author & Equine Activist

Known as the Galloping Nurse, Jane Holderness-Roddam could ride a horse before she could walk. The first-ever British female eventer to compete on the Olympic level, she and her team would gallop to Gold at the 1978 Mexico City Olympics. She is also a two-time winner at the Badminton Horse Trials (1968 and 1978) and one-time champ of the Burghley Horse Trials in 1976. On top of it all, Jane also served as a lady-in-waiting for Princess Anne for more than 30 years, built a career as a nurse and authored more than 20 books about equestrianism. She now serves as an active trustee of The Brooke Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to educating poor villagers on proper horse care.

Jane Bullen is your maiden name, but you are known as Jane Holderness-Roddam. Is this a matriname (family name inherited from your husband’s mother)?

Yes. In the old days, if a woman succeeded with land then she took the name of the person she married, as well as hers, because she was the landowner. In fact, Bullen was actually Symes-Bullen. I think Holderness-Roddam was my husband’s grandmother who married a Roddam, and so the Holderness and the Roddam became joined. Occasionally, you see people with three different names. I know somebody with five names. A similar thing happens with multigenerational women landholders.

You are one of six children. How many brothers and how many sisters?

Three brothers, all older. I have one sister older than me and one younger.

Both of your sisters were accomplished equestrians?

Yes, and my middle brother as well.

Where did your love of horses come from?

I think it was my parents really. My father was in the cavalry regiment in the First World War. He was very much involved with horses. My mother and her sister had a small circus, which they used to entertain the troops. They had a wonderful little pony they taught to lie down, blow out candles, count and do all sorts of things.

Was your mother an accomplished equestrian?

Yes, but she was actually more known for being an equestrian artist and illustrator of books. She illustrated about 40 children’s books in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s.

She was a very bright and lovely woman.

Yes, she was. Sadly, she died when she was 51, very young, from cancer. She influenced us tremendously and taught us a lot growing up about the values of life.

How old were you when she died?

I was 16.

Your younger sister was how old?

13.

Did that affect you both?

Yes, it did. I was a weekly boarder at school. When we knew it was getting near the end for my mother, my younger sister came to the school. That was helpful for both of us because we were at that age. My next sister was five years older. She left school and ran the stud for my parents. It was tough, but we were well prepared for it, I suppose, if you can ever be prepared for something like that. My mother was always very open about her breast cancer, but then it went to her spine.

Did your father remarry?

No. He died a couple of years later.

What drew you to nursing?

My mother was a nurse, and I was very influenced by her so off I went into nursing. My younger sister went to a secretarial college after school. Our eldest sister kept an eye on us and arranged for us to have a little flat in her mother-in-law’s house, which was great.

When did you begin riding?

I rode a horse before I could walk. Actually, I was bone idle as a child, so I think they plumped me on a horse for exercise.

You began competing at what age?

Three, I think.

You are considered one of the great matriarchs of the equestrian world. What was the first serious competition that you won?

That’s a difficult question, actually. I suppose when I was a teenager, the Pony Club Championships, Junior Championships. I won lots of showing classes, but that was not very difficult because they were judging the pony. I was just a steerer on top. I would say The Pony Cup Championships first and then winning Badminton and Burghley.

Was the Badminton Horse Trial your “coming out?”

I think it was, yes. Definitely.

Tell us about your horse, Our Nobby.

Our Nobby was amazing. He arrived on our doorstep with a farmer who asked if we wanted to buy an ass. He was not an ass actually. He was a pony. He was a little weedy thing. He gave the whole stable ringworm about two weeks after we bought him, so he wasn’t very popular. My mother really bought him to sell to our next door neighbor’s son, but we couldn’t because Nobby got ringworm. We bought him for 120 pounds. He was the one that took me from the Pony Club right through to the Olympics. He was an amazing animal.

Your love affair with Our Nobby was one of a kind. Why?

We grew up together. He had arrived before my mother died. In a way, he was a link to her and helped me through that process. Inevitably, it’s the same sort of relationship with any animal, isn’t it? You bond with them in a special way when something like that happens. We had our good and our bad times. He was very nappy. He could be very naughty. There were times when my brother, who was 6’2”, couldn’t get him to go where he was meant to go. I remember my brother wanted to go to the right, and Our Nobby took him to the left. My brother’s legs practically touched the ground. He was so much bigger than the pony. Nobby had a difficult streak. But through time and help from my oldest sister, Jenny, we eventually got him thinking forwards rather than backwards. That created a bond because we got there by a compromise. Life was one big compromise with him. He taught me a lot. Hopefully, I taught him a bit too in the end.

How many years did Nobby compete?

He competed until he was 13. I retired him from top competition after the Olympics. He went on until he was 27. Nobby was the schoolmaster for some of our students. If he didn’t want to go where they wanted him to go, he just wouldn’t. They often would come up and say, “We can’t get Nobby down the drive.” Nobby would come back, and the look on his face would tell you a lot.

He had tremendous willpower.

He did, yes. He did. He did. He was extremely obstinate. It’s all about partnership with these top competition animals. The partnership between horse and rider becomes a complete bond. Each knows how the other will react. It was quite revealing to see how sensitive some riders were toward what Nobby was doing. You could often tell who was going to be a good rider, and who wasn’t going to be, by Nobby’s reaction to them.

The Galloping Nurse was a name you were given because of what happened the night before the Badminton Horse Trials?

Typically, the night before a competition is the time when you reflect on what you must do. I always try and plan my ride. I ride every fence as I hoped it was going to appear. Of course, it never quite works like that because the unexpected always happens. The horse slips or something—some object is not where you thought it was going to be or the fence looks different when you come to it. So it’s quite difficult, but I think it is helpful if you have the plan in mind. My brothers and sisters taught me to have a Plan B so that you are never caught off guard by something going wrong, which inevitably happens, however good you are. So, I liked to go through everything mentally and try to get a good night’s sleep. My brother’s advice is to have a very good breakfast the morning of the competition so that your body can cope with the challenge. You also rely on your groom to do the same for your horse.

What happened the night before you won the Badminton Horse Trials?

I came off the night shift on the Thursday morning, and then I drove down to Bebington, which is about a hundred-mile drive from London. I missed the briefing, which was usually on the Thursday morning. I remember everybody saying, “It’s the biggest course ever, and you’ve never seen anything like it.” Later on, I learned that every year somebody makes that comment. But at the time, it seemed daunting which made me more determined to show everybody that we could do it. That’s the great thing about being young and stupid. You think you are better than anybody in the world, and you can just do these things.

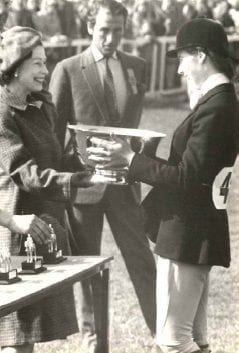

-

Queen Elizabeth presents the trophy for Jane’s unprecedented win at Badminton.

- That same year you were selected for the Olympics in Mexico. Who were the other women chosen at the time?

There were three women on the “Long List,” as it was called. Any one of us could have been the first, but I was the one that was chosen because that was the year I won Badminton. And then the next selection sort of trial, the final trial, was the Burghley Horse Trials in September. In those days, it was what was called long format with all the roads and tracks and steeplechase. It was a 17-mile competition, which you would never really dream of doing just before something like the Olympics. Their advice was simple: “You don’t need to go fast.” I only had one gear in those days, and with Nobby, everything was just gallop. However hard I tried to slow him, it took more energy out of him trying to slow down. So, I just left him to it in the end. We finished third in the Burghley Horse Trials and were selected to go on that performance. So, that was amazing.

You were the first woman to compete for Great Britain. Were you ever frightened?

No, I wasn’t. I had great confidence. I think I was a little cocky at that age. I had great confidence that Nobby could do anything; I think that’s a great thing. I’ve since learned how important partnership is because I had other horses subsequently. They weren’t as good, and I did get nervous with them because I didn’t have that supreme trust that is vital to a good partnership.

How did you build that trust with him?

It was slightly trial and error. Making mistakes is probably the best way to learn. He also was incredibly clever. He was very athletic, which made up for his size. He could put in that little extra sort of effort where a bigger horse wouldn’t be quite so lucky, I suppose. Having grown up with him, I had even more time to build upon that partnership.

Tell me about the Olympic gold medal team for Great Britain?

We were a bit of a strange team really because we had the Galloping Grandfather, Derek Allhusen. He was 56, which was considered quite old back then. We had the Galloping Sergeant, Ben Jones, who was training in the Army at the time. We had the Golden Wonder, Richard Meade, who was very good-looking and dashing with golden hair and all the rest of it. He was everybody’s heartthrob. And then there was me, the Galloping Nurse. We were a pretty strange bunch of people, and I don’t think anybody gave an awful lot of hope for us to take the gold. But they were quietly confident we wouldn’t let Britain down. They felt we were fairly able to get around. They were a great team, and they looked after me so well. They were very protective of me. I was put in the safe slot, second, because the first one was the pathfinder. I was the dodgy one. Nobody quite knew what was going to happen. The other two were the safe ones. So, you needed to get three out of the four of you safely around. I did have two falls. So, I was the dodgy one in a way, although I held the second-fastest time along with America’s Jimmy Wofford, in spite of my two falls. I finished 18th after the dressage; every fall is 60 penalties. Nowadays, you’re eliminated if you fall. They wouldn’t let you continue. But, in those days, you could carry on, falling off as often as you liked till you got to the end. It was an amazing team effort really. It—the competition—would have been stopped nowadays because of health and safety. They had these terrible floods in Mexico, and the whole course flooded. They would have monsoon rains in the morning, and then it would dry in the afternoon.

You were the first woman from any-country to win an eventing gold medal?

Yes, that’s right.

Were you surprised?

No. It was only afterward, when everybody said, “Oh, gosh, you’re the first woman,” and this, that and the other, that I realized what I had done. Somehow it didn’t seem real because quite a lot of girls did compete and had done so in Britain for quite a long time. It was only when people started to talk about it a lot later than it set in. Being known as the Galloping Nurse was really much more of a story than the fact I was the first woman. The fact that I was a training nurse competing was more interesting.

Eight years later, you won the Burghley Horse Trials but not with Our Nobby.

Burghley, yes. It was actually ten years later. My second really good horse was Warrior. An American named Suzy Hart owned him from Far Hills, New Jersey. She was a wonderful owner. She got this horse for me after she’d seen me ride in Mexico, and my brother was a great friend of hers. She said, “I’d like to get Jane a horse.” She allowed him to compete as a British horse, which was really wonderful. So, he competed for Britain although he was American owned, and he won both Badminton and Burghley. He won Burghley in ‘76 and then Badminton in ‘78.

Was the experience the same on Warrior as it was with Our Nobby?

No, completely different. He was a very, very good jumper. It’s not that Our Nobby wasn’t, but he was just quick and fast and didn’t think about what he was doing. He just went instinctually. Warrior was very much a thinking horse. I really had to learn to think as quickly as he did because he would never put himself into any dangerous situation. He would stop quite often if everything wasn’t quite right. Thanks to him, I learned to ride properly. I had luck on my side with Our Nobby. However, Warrior was the one that made me into a rider because everything had to be right, and then he would do everything right.

Jane racing in the famous Paul Mellon Colours at Newbury in 1973.

You received the Commander of the British Empire?

Yes, it is an honor you are given. Somebody must put your name forward. At the time, I was chairman of horse trials, and we were going through some very bad patches—horse rider fatalities and awful things like that. We also had foot and mouth. The sport nearly collapsed in the UK. Apparently, somebody thought I handled it well, so I was awarded the CBE for that.

You serve as lady-in-waiting to Princess Anne. How did that happen?

She rang up and asked me to be one of her ladies-in-waiting way back 30-odd years ago. It was a bit of a surprise because I wasn’t quite sure whether it was her or not ringing up because I hadn’t spoken to her on the phone ever before. It took a bit of time to be certain it was her and to grasp what she was asking of me. She asked whether I would be one of her ladies, and she gave me the weekend to think about it. I rang up a couple of the other ladies-in-waiting. So, with fear and trembling, I went back and said yes.

What does it mean to be a lady-in-waiting for a princess?

You are a companion on her official visits. You also deal with any issues that might arise and try to make sure the program is run according to the timing of her schedule, which has to be exact. If the princess has two or three engagements in a day, you can’t run over on the first one and then shortcut the second. Timing and schedules can be quite important if flights and things like that are involved because one mistake upsets the whole system. A companion is also somebody for her to enjoy a bit of a laugh with. We might experience very funny situations, sad situations, some dodgy situations or whatever. All sorts of things can happen. Another responsibility is to make sure that everybody that should meet the princess are included in the day, because some people will always hang back, and some people will always push themselves forward. A lady-in-waiting must manage the events to ensure everyone is included.

Nine ladies-in-waiting. How are you organized and managed? Is it by the day?

Twice a year, we have a get-together and go through her entire program. Princess Anne likes certain ladies that are particularly involved in some of her charities to do those things with her. Most of us are fairly horsey, but I would go with her to all the FEI meetings when she was president of the International Equestrian Federation. That was great fun because we met different people and went to different parts of the world. We all share the days, but she always likes people that are particularly involved in whatever the program is at that time to accompany her. It makes it more interesting, though you never know what you’re going to be doing from one day to the next. It’s extraordinary. It is usually a one-day thing unless you go on a foreign trip with her. The longest I ever traveled was an amazing 22-day trip soon after I started. We went to five different countries and did something like 80 different engagements. We met kings, queens, prime ministers and presidents. I did not have a clue what I was doing, but I learned as we went along. She is always very patient.

Do you consider the Princess a friend?

Yes, I think I would. I have known her for a long time.

One of the ways that you are known to “pay it forward” is with The Brooke Foundation. You serve as a board member for Brooke and so much more for that organization. How did that come about?

I am not quite sure how it came about. I think somebody in The Brooke asked me to go for an interview, which I did. Previously, I had been with the World Horse Welfare, a similar organization; it started just before The Brooke. Because of the War, all the injured horses were going to slaughter for meat. It has been an ongoing thing for the World Horse Welfare to try and stop that trade. The Brooke has a slightly different approach, a more philanthropic approach, I think. I was very impressed with the way they managed everything, and I looked thoroughly into what they were doing. The mission wasn’t just sending money out for this, that and the other. It was actually going in the field, so to speak, finding out what the problems were and really looking into how they could help. The focus was not just the animals but also the communities and the people that looked after those animals or didn’t, as the case may be. Finding out why and what could be done about an issue really impressed me. I think what they do is phenomenal. They really find out what the best approach is looking forward. I think that’s very impressive. I have only been on the one trip with The Brooke because of timing. I was going on a trip to India and Pakistan, but sadly, it had to be canceled for security reasons. Hopefully, I will go next year. They have another trip, and I will try to go to that one because the work is in the brick kilns, which is particularly difficult for the animals and the local communities. They have problems with poverty, lack of education and how to look after animals and themselves, in a lot of cases. Some of it is so elementary. But to these people, they traditionally (for years and years and centuries) have done things a certain way and have never been shown another way. The world has changed, and it can change even in the poorest communities. I think the work The Brooke does is very impressive. They have a very good team of people that go around all over the place and make a difference.

Jane in Senegal on a trip with the Brooke Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to educating poor villagers on proper horse care. Jane became a trustee in the organization in 2013.

What life lesson might you share with a young woman just coming into her own?

I would tell her to think about what she wants to do and how she wants to do it. I would remind her that she must work at it and achieve it herself. Do not expect everybody else to help her with her success. She must go out and do things for herself. She must learn by her mistakes and then put those lessons into practice. If she is a rider, learn from mistakes and relate it back to how she rides horses. I think the system has given too much help too young. That’s difficult for the young because they expect people to do things for them. I would say to her that is not real life. You have got to get out and really push yourself hard, help other people and don’t expect success to come to you without really working for it.

This article was first published on July 2, 2019