Mary Alice Monroe

Mary Alice Monroe lives by the guiding principle, “If they care, they take care.” For her, this exemplifies her mission as an author: to help readers become aware of the issues facing endangered species. Mary Alice has felt an inherent bond with animals and a passion for nature since childhood, which she uses to craft captivating stories that identify important parallels between nature and human nature. Under a rigorous writing schedule, she has published over two dozen novels and has had more than 7.5 million copies published worldwide. All the while, the prolific author is an active conservationist and has volunteered with the Island Turtle Team for over twenty years. Her most recent novel, On Ocean Boulevard, released on May 19, 2020.

You are the third born of 10 children, five girls, and five boys. Is this the origin of your love of the outdoors?

My five brothers played sports, baseball, and football, but honestly, it wasn’t my calling. I only played just to play games. I was outside to sing to the trees, look for fairies and elves. I loved flowers, trees, birds. I was always interested in nature, even as a little girl.

There is a consistent element of nature in all your work. Why?

There is. A few years ago, I went to go see the tomb of St. Francis of Assisi in Italy. I have always loved St. Francis. I remember when I was young, I used to pray to Saint Francis all the time because the statue always had a bird in his hand. I loved the stories of how the animals loved him. Yes, from very early on, my love of animals and my wanting to make a connection with them was always there.

Your father was an interesting man. He was a physician?

Yes. A pediatrician and there have been jokes about his 10 children . . . populating his own practice. My father was born and raised in Germany and came in the 30s, before the war. His talents were always in music, which was his true passion. He was a concert-level pianist. When he was young, he had short pants and a strong German name, Werner, which didn’t go well in the ‘40s in America; I think he was beaten up regularly at school. He told me that “one of his big days” was to own long pants. He played the organ in the church and participated in many activities that would probably label him a “nerd” today. He was always involved with music and science and philosophy. I think of my daddy as a Joseph Campbell kind of a man; he made a living being a physician, but he was much more of a philosopher.

You attended a girls’ boarding school, outside of Notre Dame, for three and a half years?

Yes, it was the motherhouse for the Franciscan nuns.

Was there an epiphany of sorts that you had?

Indeed. We started each day with mass. And we went with the nuns to the grotto at 5 o’clock, where we said our afternoon prayers. It was outdoors, and beautiful. There was a clarity of spirit at that time, and I remember a feeling of serenity that I wanted to hold onto. I still seek the quiet moments where you feel that you hear the wind, hear the water and can smell the blossoms. That is my definition of a state of grace.

And you’re married to an atheist?

Well, not quite an atheist. He says he’s a Taoist, but he’s not declared himself. Let’s put it that way. He believes in a higher power, but I don’t know if he’ll admit to a faith. But he has been very supportive of my faith, which is important.

Because your faith is central to who and what you are?

It is.

How much “alone” time do you need each day?

I spend most of the day alone. I have a very rigorous writing schedule in order to make the deadlines for a book a year. But I always have my animals with me. I have a coterie of dogs and canaries; I need their presence. I would feel alone if it weren’t for animals. My husband takes care of me now that he’s retired, and he’s my best friend. But he stays away while I’m under deadline because an interruption of thought when you’re writing can set you back for hours.

Can you describe the day-to-day discipline of writing?

There is a lot of pressure when I’m under deadline. There are two stages of the writing schedule. When I’m under deadline, like I am now, a writer is either working on the story or thinking about the story. Days can go by before I will leave the office. I’ll roll out of bed in the morning, feed the canaries and the dogs. In turtle season, I often get called out to the nests. By 9 o’clock, I’m in the office. And if I’m under deadline, I will not—and this is hard—go online for emails and check all the social media because that’s a time-suck.

How long do you sustain that deep focus?

Three, four hours at a time. If I hit the “zone,” I call it “plugging in,” I just let it go on. I work 24/7. But I can’t sustain that for long. At the beginning of a story, it’s like chiseling rock. I get up and walk around. I will work from morning to dinner with breaks to get up every hour or so to just walk or to take the dogs, to water the flowers, just to get my blood moving. But later on, in the story, I will work till midnight. It’s that intense.

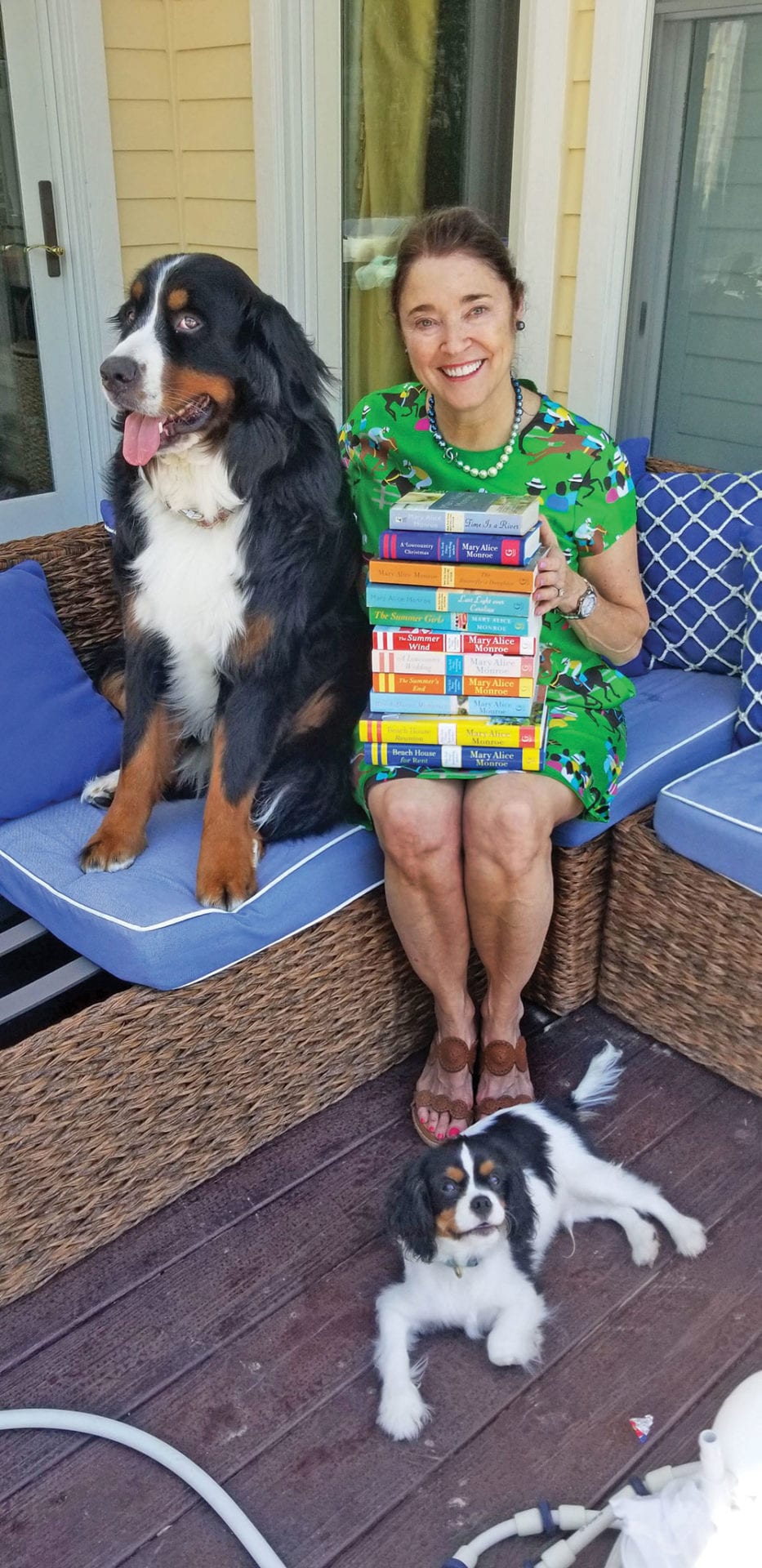

Mary Alice holding a stack of her novels and sitting with two of her dogs, Vega and Cosmo.

How long can you sustain that regimen?

I work every day for a varied number of hours. But that intense period is usually two months.

You have written and published over two dozen books, which is effectively a book a year, so it’s two months of just sheer focus.

When people say, “It took me 10 years to write a book,” I am envious of that. You get to pull it out and dust it off and think about it. But they’re not writing with the schedule I am. I am in the zone for two months where I don’t even go to the grocery store. I am just in the book’s story. Once the first draft is done, I begin revision. That too, is intense. The editor usually wants it back in short order. At this point, I pull out the tool belt and use my craft. I revise the manuscript four or five times before it goes out to the public.

Do you ever take serious breaks from writing?

I need to and I’m trying. I have a house in North Carolina now. I bought it to escape from the yearly hurricane evacuation. It’s become a place of solace and recharging batteries. You have experienced loss with the death of two authors and friends: Dorothea Benton Frank, and Anne Rivers Siddons. Dottie’s death hit very hard because it was so unexpected, and she was so alive. No one saw it coming. We knew Anne was ailing, but still, her death hit hard. There are two kinds of reflections that go through one’s mind on the loss of a friend. First, of course, is that I’ll miss her. The second is to remind me to pay attention to the quality of my own life. I wish Dottie was given time to spend with her children and grandchildren, who she adored. And they adored her in return.

What is your goal for your career?

There are two. Number one was defined 20 years ago. I made the decision when I was on the turtle team – I still am by the way. I was mentored by the great Sally Murphy, so I was aware of what was happening on the beaches with sea turtles. I was a successful author and decided to use my books as a force for good. To help readers become aware of the issues facing endangered species, and more, to care. Because if they care, they take care.

How did that manifest?

Beyond my dreams. The first book I wrote was The Beach House. That little book caught on like wildfire. Old school. There was no internet, just word of mouth. It was my first New York Times bestseller and more, it greenlit my ability to continue in the genre I’d created. And it showed that I was right; people do care.

What is the “why” of your writing?

To bring awareness of not just endangered species but our connection to them and to nature as a whole. And once we connect to nature, we are connecting with the most fundamental part of our souls. And it is in that quiet that we hear God. We react viscerally. If we can hold power inside of us each day, we have better relationships, we remain more centered because we’ve gone beyond the petty into something so much bigger. If we can get people outdoors to connect to nature, I believe their lives will be enhanced.

What is your preference . . . the beach or the mountains?

I could have easily answered the beach before, but I’m really in love with mountains too. We had a family farm up in Vermont. I spent summers there with the children. If you ask them what their best childhood memories are, they’ll always go back to Vermont. I taught them the names of the plants and the flowers, the wildlife and the birds. To be back in the mountains now is being back at that place. Trees have power.

Trees have great power.

Yes. And so, does the ocean. But it’s different. I don’t get inspired as much in the ocean.

It’s calm.

Exactly. More relaxing. Staring at an ocean vista is like pushing a delete button on my worries.

And the forest is fierce?

More creative. Like compost. It’s organic. You can almost smell it.

Of the books you read, what is your favorite?

Always a tough question. My all-time favorite novel has to be To Kill a Mockingbird. But there are others. Pat Conroy’s Beach Music is one of my favorites. Shogun is another because it connects to my background in Japanese-Asian history.

What book did you write that you consider your favorite?

The Beach House. It was a book of my heart. I wrote it for no other reason than I thought I could make a difference. I put everything I had into it. I even changed the manner in which I wrote a book. I had never read a book like it, nor had I written one like it. When I finished and submitted it to my publisher, it was a little mass market. Nobody, not even my editor, knew what to do with this book set on a beach with nature. I just wanted it out there. The rest is history. I knew I’d created my own genre, and because of the book’s success, that book was the basis for everything I’ve written since. Is it the best book I’ve ever written? I don’t know. But it is very dear to my heart for that reason.

Did you spend more time on that book than other books?

No, I think it does not take a long, tedious amount of time to write a novel if you truly feel it. I knew the story in my bones. It had been simmering for a long while. It’s always this way. I choose a species first. Then I do an academic study, I talk to the experts, then I roll up my sleeves and work with animals. The story is organic to my experiences.

New York Times bestselling author; Published over two dozen novels and 7.5 million copies worldwide; Inducted into the S.C. Academy of Authors’ Hall of Fame; Awarded the S.C. Award for Literary Excellence, RT Lifetime Achievement Award and the Southern Book Prize for Fiction; active conservationist and volunteer; serves on multiple conservation boards.

How did The Summer Guests begin?

The Summer Guests began with the horses. I started working with rescue horses near Tryon and Campobello. I thought there was a story there. It was intellectually there, but emotionally, I never made the connection to the rescue horses. That is, until I fled from hurricane Irma to the farm of a friend in Campobello. I stayed with a group of evacuees, mostly from Florida. It was one of those unique times in your life that you know you’re meant to be in that place at that time. I had to evacuate with 3 dogs and 5 canaries. Where do you go? The hotels don’t want you, so I called my friend. Cindy B. said, “Sure, come on up. It’s going to be crowded.” When I arrived at her horse farm, there was a couple from Miami with their horse and a huge giant Schnauzer who was old and cantankerous. He didn’t like us much. There was a couple from Venezuela who came up from Wellington, FL with their beautiful Grand Prix horses. Cindy’s daughter Mary came up with her newborn baby and a Boykin Spaniel. The Boykin was intact. The reason I mentioned that is because one of my dogs, my little Cavalier Gigi, was in heat that weekend! It just added to the mayhem. Because the hurricane was bouncing back and forth on both sides of the Florida coast, it was the largest evacuation in Florida history. Two hundred and fifty-plus horses were coming up from Florida and then Georgia and South Carolina. They landed in Tryon, North Carolina. The Tryon International Equestrian Center, with Katherine Bellissimo, opened up their stalls as a refuge. It was enormously generous for the horses and for the people who stayed at the hotels. We were all helping with the horses; Grand Prix horses, school horses, and rescue horses. It was one of those moments when you really feel good because you’re helping others in a tough time. Isn’t that when the human spirit shines brightest? I came back one night from the barn to Cindy’s house, and the women were all in the kitchen. Of course. What a scene. We were in our jeans and smelling mucky. Laura Rombauer gave us some great wine, and we were listening to music and talking and laughing and bumping hips to the music. The baby was crying, and from the windows, you could hear the dogs outside were howling. Why? Because my little Gigi was sitting at the window. In heat, if you recall! Leslie Munsell, the owner of Beauty For Real Make-up, was doing makeovers. “You look good in this color.” I looked around at the generations mothers and daughters and friends, all of us in our dirty clothes, feeling closer, working hard, laughing hard. I thought, “This is what I will write about. Women helping women. Women supporting each other. Being together in good times and bad.”

The horses and the comradery among the women were the inspiration?

Yes. It all began with Cindy. One family was given the cottage, another the lake house. I was put in the barn upstairs. I thought, “Okay, no room in the inn because I brought my canaries and my three dogs.” It was actually a charming apartment with a loft sleeping area, which was really pretty. The barn is gorgeous, better than most houses! There were two wooden doors that opened up to the stalls below. There were several horses there. I could smell the clean hay, the leather, the feed—it was so comforting. When I went to bed that night, the TV was on blaring the weather reports about the hurricane coming. I lay there and wondered if I would lose my house, my personal things. I was shaking. It was then I heard the horses communicate to one another. They whinnied and snorted and kicked the stalls. I was listening to a lullaby of conversation, and my blood pressure went down. I slept like a baby. The next morning, I got up and went down to the stalls with a steaming cup of coffee. When I entered the horses were circumspect. Horses don’t just come right up to you. Slowly, I got to know them. Over the next couple of days, I fed them and brushed them. By the time I left, when I looked into their eyes, I knew they recognized me. Horses have the most beautiful eyes, don’t they? Those big, watery, brown eyes.

Like all animals?

Not all. Dogs, for sure. And dolphins. I always say to people, “Don’t feel you have to touch them. They look at you, and they know, believe me, they know who you are. Once I made that connection with the horse, I thought, “Now I can write about horses. Now I feel it.” Do you feel that people have the urge to touch all animals? I think most people who have a pet do. What I try to show in my novels is the best way to be with wild animals is to remain quiet and respectful of their space. The human instinct is to touch; we want to touch that dolphin or that horse. Instead, we should trust our ability to connect with our eyes. Learn the body movements of the species you’re with because communication can take many different forms. Communicating with the wild is different than with your dog or your cat. First of all, you won’t scare them off. And you will be safer. Secondly, you’ll come to know that there’s a world of communication available to you if you are mindful and respectful of the other species and trust your inner spirit.

When you’re not with animals, do you feel something is missing?

Yes. Especially when I’m confined, like when I am on a book tour or under deadline. I’m inside for weeks at a time.

I find the dichotomy between the isolation required to focus on writing and then the immersion with people needed in your profession interesting. How does this work?

I need both.

You do?

I love being with people.

Really?

I really do, especially with people I know. I’m not fond of cocktail parties. I love being with friends. Over dinner, a glass of wine, hiking. I love making connections. I love laughing. I need that outward expression because it feeds the inner. If I’m alone too long, I get a little squirrely. I especially love the one-on-one with a best friend.

ELYSIAN Publisher Karen Floyd and Mary Alice share a laugh together during the interview.

When you are in the most focused portion of your writing, going 10-plus hours, and you’re in the “zone,” do you need people to recalibrate?

Not during the process. I don’t see anybody. Actually, I don’t even want to talk on the phone. I don’t want to interfere with what’s going on in the world in my head.

Do you “need” the book tour to fill the part of you that is an extrovert and to create?

That’s a really good question. Do I need that? Professionally it is important. Speaking requires a great deal of energy. I’m not a fearful speaker; I don’t fear crowds. It doesn’t matter if I speak to a group of 10 or 500 people. I prefer extemporaneous. The give and take with an audience. I feel their energy, and I need it. Best of all, however, are the private moments when a reader tells me her story afterward, I don’t rush them. I want to hear what they have to say. I truly am interested.

As a child, you were connected to nature . . . inventing and creating stories, in your mind, about elves and fairies and the like?

Yes, and writing stories and composing songs. I still look for fairies!

You have a complete attachment to nature, but you also have an innovative creative mind. Do you remember when you merged the two?

Well, I wrote my first story when I was eight years old. “Willy the Wishful Whale.” I really loved the story and was proud of it. My daddy called me into his office. “Mary Alice,” he said in that voice that told me I was in trouble. He thought I had copied it, and he was telling me never to copy anyone else’s work. I was horrified. I don’t know if he believed me. I didn’t show anyone my writing for a long time. My third-grade teacher Mrs. Crawford came up to me and said, “Mary Alice, did you ever think you might want to be a writer when you grow up?” And I remember being stunned. I didn’t know that was a job! My teacher named what it was I wanted to do.

Did your father, who is no longer alive, ever tell you well done? Did he ever appreciate your God-given talent?

Sadly, he never lived to see my first book published. Yet, he came to admire my determination. He was old-fashioned when it came to a woman’s role in life. He didn’t worry whether the girls went to college. Even though I was an academic. He was surprised when I was awarded scholarships and fellowships. In his mind, I needed to make a good marriage. My mother was more dynamic, and lived to see my first book published.

You did attend college.

I started at Northwestern University in the Medill School of Journalism. But I left after one year.

You had some interesting jobs in between college.

I learned more from the lessons at my job than any course I ever took. I left college and took a position at the Encyclopedia Britannica. That was a big deal in Chicago at the time. They were creating a new edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Back in our day, Encyclopedia Britannica was our Google. They were hiring the best minds for editors and writers. I was hired as a general assistant secretary, but I worked my way up very quickly to the assistant to the general editor, Warren E. Preece. Through him, I was in touch with experts in multiple fields all over the world.

You learned the art of writing and editing?

From the best of the best.

How many people were working on the project?

There must have been 50 or 60 editors and hundreds of writers. We wrote letters to the contributors who were experts all over the world.

Which is our modern-day Wikipedia.

My other boss was Mortimer Adler, who was a great mind in the field of education. I saw less of him, but Warren took an interest in my learning. He actually asked me occasionally, “What did you think about this?” He mentored me. I’ve been fortunate in my life with mentors. I hope at this point in my life, I can be a mentor to others.

What was your detour? I know that you were married.

I was married young. We sold everything we owned and went on a six-week honeymoon to Japan. I knew little about the country. This was the 1970s, and the big splash Japan made on business in the United States hadn’t yet happened. During that trip we went from one Japanese Inn (ryokan) after another. I clearly remember sitting in one of the great gardens of Kyoto when I experienced the sensation that I’d come home. They call this “the whisperings of the past” when you are sure you’ve been there before.

Do you believe in reincarnation?

I believe it is a possibility. I don’t know how else to explain its effect. And why not? I felt at peace, sure I had been there before.

Then you . . .

I came home, changed majors to Japanese. There were very few places where on could study Japanese at that time. My husband was in medical school in New Jersey, so I received a scholarship and went to Seton Hall. I graduated, became bilingual then did my graduate studies in Asian studies. I went from writing English to Japanese and Asian history and culture.

I don’t see any of the Asian studies in your genre of writing.

Not yet! I have a novel in my heart. When it comes out, you won’t be surprised. I’ll write that someday, God willing.

Are these love affairs with your books?

Yes. Especially with the animals, I connect with. I share that passion with my readers.

Mary Alice Monroe, share with our readers something personal. Tell your younger self something that you wish you would have known, perhaps a lesson that you have learned.

Take your time, and enjoy the day. I was very driven and maybe still am, to accomplish tasks and to get work done. I used to focus on whatever I needed to get done. That kind of thinking leads to living in the future. I would tell my younger self to live in the moment! To journal all the details that you think you will never forget. You will. We all do. Especially to all the young mothers out there, write a journal about everything that gives you pause or surprise about your children. Write it down, because it goes so fast.

This was first published on October 13, 2020