Mavis Spencer held off Hollywood deals and an Ivy League college for equestrian life

Mavis Spencer held off Hollywood deals and an Ivy League college for equestrian life

By Rebecca Carr

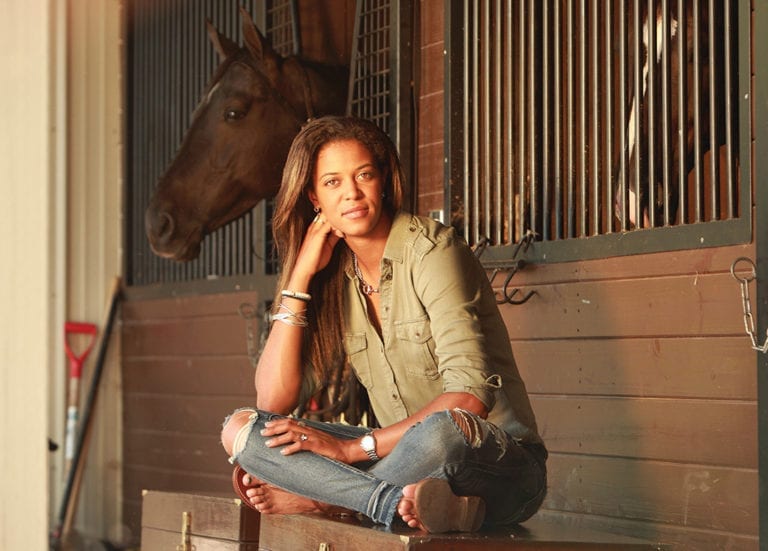

Photographs by Josh Norris

Before the sun even had a chance to rise, little Mavis Spencer blazed into her parents’ bedroom with an urgent message: “Today is the day!”

“Yes, it is. Happy fifth birthday, Mavis!”

“No,” Mavis corrected her parents. “Today is the day that I get to start training a horse!”

Making good on a promise, her parents rolled out of bed and took Mavis to a barn near their home in Santa Monica, California, for her first riding lesson, something she had dreamed of doing since she first sat on a horse at the age 2. And in doing so, they unwittingly launched what would become the soaring riding career of Mavis Spencer.

Mavis Spencer had stint as Miss Golden Globe 2010.

Now 26, Mavis is considered to be one of the top riders of her generation. US Equestrian, the national governing body for the equestrian sport, recently tapped her to be one of eight ambassadors in a worldwide campaign to spark the joy of riding in as many people as possible.

As Mavis rode that day in celebration of turning 5, she grinned from ear to ear with pride. Riding a little white pony felt just as she had imagined — smooth, with an unfolding sense of freedom. That is, until a low-flying plane spooked her mount, dumping her rather unceremoniously on the ground.

“I think my parents thought my love of riding would be over right then and there, but it was just the beginning,” laughs Spencer, estimating she has fallen 30 to 40 times since then.

Falling off and finding the will within to get back on.

It is a rite of passage for all riders. The same determination that Mavis used at age 5 to get back on her pony has stayed with her as she advanced through the ranks of the horse show circuit. It has spurred her forward at major national and international jumping series, such as the Equerry Bolesworth International Horse Show, the World Equestrian Games, and the Longines FEI World Cup Jumping Series.

Her parents, Emmy-award winning actress Alfre Woodard and writer/producer Roderick Spencer, did what they could over the years to sway their daughter toward other, perhaps less dangerous and less expensive, sports. Tennis, gymnastics, basketball, ballet, and hiking. You name it, they tried it. But something about the majesty of horses, something almost spiritual, kept calling her back. And so her parents did something that can be difficult to do as parents. They let her go. They let her pursue her dream of an equestrian career even if it meant giving up the Hollywood movie offers that followed her stint as Miss Golden Globe in 2010, delaying an Ivy League college degree and taking up the nomadic life of a groom.

“I wanted our children to pursue something they felt called to do even if it meant no money and rejection,” Alfre Woodard said. “If you work at what you love, it will be satisfying and liberating. They both saw that in our work. We believe that you should stay true to the practice and honor the sacred discipline you’re called to do. If you follow your passion, not the paycheck, you will surround yourself with other like-minded people, and you will have what matters in life — joy.”

US Equestrian sees Mavis as the face of the future of the sport — someone who worked her way up from the position of groom to the top of the Grand Prix ring through sheer hard work and determination. As US Equestrian, formerly known as the US Equestrian Federation, overhauls its image to make riding more accessible to riders of all socioeconomic backgrounds, they want to highlight competitors like Mavis — talented, whip-smart, stylish without pretension — someone who has made it on her own, said Vicki Lowell, chief marketing officer at US Equestrian.

“Mavis is a trailblazer,” Lowell said. “She is someone who really put her all into working her way up and will be an inspiration to upcoming riders.”

With her growing social media following on Instagram (32.5k followers in June) and down-to-earth demeanor, US Equestrian hopes Mavis will inspire young riders from all backgrounds to pursue riding as a sport. Seeing the same qualities in Mavis, two dozen major equine brands, such as American Equus, the stirrups and spurs maker, and the elite French saddle maker CWD, now sponsor her as an athlete.

In addition to competing at the Grand Prix level, Mavis is combining her palpable smarts and people skills to run the U.S. division of the Neil Jones Equestrian as well as to sell horses and train clients through her own company, Gallop Apace, LLC based in Wellington, Florida.

“I want to share my own experiences in the most honest way possible so that kids know that they don’t always have to have a ton of money behind them. If you work hard, you can get there,” Spencer said.

U.S. Equestrian sees Mavis as the face of the future of the sport.

Growing up Hollywood

Mavis grew up in the glow of successful Hollywood parents, but her parents kept things simple. They taught Mavis and her younger brother, Duncan, the importance of hard work and earning their way. Their father always told them: the harder you work, the luckier you get. That lesson paid off for Duncan too. He is now a professional golfer in Arizona.

“They told me I had to go out and make it on my own,” said Mavis. “My parents kept us really grounded. They made a huge effort to have us grow up as normally as possible if there is such a thing.”

Sure, there were famous people orbiting her family and school life, but Mavis recalls that she and Duncan were not star-struck. “My parents said it is not who you are, but what you do that is important in life,” Mavis said. “I have found that to be very true.”

From the time Mavis could talk, her family had to pull over to the side of the road every time they saw a horse. She would hold out her hand and cluck until the horse would come over to be petted, her parents recall. She did not have dolls. She had a room full of Breyer horses, the most realistic version of a horse that toy companies make. Her father read her “Black Beauty” so many times that she had memorized it by the time she was 3 and would let readers know if it was not read in its entirety. Then came the movie, “The Black Stallion.” She watched nothing else for five weeks straight, prompting her mother to ask the school if that was normal.

Mavis loved horses so much that she would set up a course of jumps in their home and fly over them. She trotted and pranced around her preschool classroom pretending to be a horse. Every school project was about horses, even math assignments.

“From the time she could talk, when she was a little tiny girl in diapers, she would point and say, ‘What dat, Daddy, what dat?’ I would tell her, ‘A horse.’ She would repeat the word horse and say it like it was the most beautiful thing in the world,” Spencer said.

Mavis shared her first pony, Norton, with another horse-crazed girl. Despite all the attention, Norton kept throwing them both. When the other little girl broke her back after getting dumped by Norton, Mavis’ parents decided it was time to get a more reliable mount for their daughter.

Enter Seashell, a pony almost large enough to be a horse. Seashell was an earnest friend. When Mavis fell one day, Seashell stood right by her side and nudged her with her nose until she could get back on. She rode Seashell until she was 11 and had grown too tall for ponies and needed a horse. She had grown so attached to Seashell that she still owns her today. Toy Story, her first horse, came from the Spielberg family. She continued to compete successfully at all levels, rising up through the hunter ranks.

“If she could have been at the barn all day, she would have,” said Dick Carvin, who along with his wife, Francie Steinwedell-Carvin, and Susie Schroer started training Mavis in 2000 at Meadow Grove Farm in California.

The Carvins recall how Mavis stood out at their barn because she would stay long after she was done riding to help other children who had multiple horses by jogging and grooming them. “She was never jealous that they had more horses than she did. She just loved being around horses. Her attitude, even then, was amazing,” Carvin said.

“The bottom line is yes, you have to have talent, and you have to work for it to make it in the horse industry. But Mavis gets the best out of horses, and you can see it in the horses she rides.”

“It did not surprise me that she would be a success because she loved all aspects of horses — care, management, riding and even mucking stalls. And it helps that she is a great rider.”

Two dozen major equine brands, such as American Eqqus, the stirrup maker, and the elite French saddle maker CWD, now sponsor Mavis as an athlete.

As Mavis rose through the hunter division to the junior level, the highest level of that division, where the jumps are 3’3’’ high, she set her sights on riding at the Wellington Equestrian Festival (WEF) outside Palm Beach, Florida.

There was just one problem. The show was smack dab in the middle of the school year. Mavis had to convince her parents to send her across the country at the tender age of 16 to compete in Florida. The teachers at the prestigious Harvard-Westlake School, considered one of the top private high schools in the nation, would need convincing as well.

“When she asked if I could get her out of school to go to Wellington, I told her to get herself out, and I would vouch for her,” Woodard said. It was an important lesson about pursuing a dream. She learned how to assert herself to ask for what she wanted.

To this day, both of her parents are amazed at her ability to convince the school, known for its academic rigor, to let her go. Mavis persuaded school authorities that she could keep pace with her peers and pass her exams by working closely with a tutor.

“Mavis is very brainy, and she passed all of those exams,” Woodard said.

After Wellington, Mavis went on to spend the summer of 2008 in Belgium working as an intern for Neil Jones Equestrian, an international horse trainer and dealer.

Success followed. That fall, she won individual silver and team silver medals at the 2008 Adequan/USEF National Junior Jumper Championship. Soon after, she secured the prestigious William C. Steinkraus Style of Riding Award at the Pennsylvania National Horse Show in Harrisburg. The following year, she went to Australia with the U.S. Team for the Youth Olympic Festival and finished fourth.

She was on her way.

The horse she moved up the ranks with was a Belgium Warmblood named Winia Van’t Vennhoff that her parents purchased for her in Holland. Winnie had never shown before, but she took Mavis to her first Grand Prix events.

At highly competitive levels of riding, it is not uncommon for horses to cost upwards of $500,000 and for riders to have a string of horses to ride. Most competitors have a groom to care for the horses and organize moving from one horse show to the next. In Mavis’ case, she had only one horse at a time, and she did the grooming herself.

“My joke with people is to tell them before a horse show to roll up $100 bills and throw them out the window to get ready for what it feels like to spend a lot of money,” Spencer said. “These girls would show up with seven grooms and big trailers with seven horses. Mavis knew it was a big budget line for our family, and she figured out how to make a living doing it. We are extremely proud of her for that.”

At 18, she told her parents she was deeply divided about going to college. She had been accepted at Columbia University in New York and wanted to go but also wanted to compete in Florida and work for Kent Farrington, one of the top-ranked jumpers in the world. While many parents would have balked, Woodard and Spencer took a different tact.

“I told her, ‘If you show up at orientation, you have to complete your freshman year,’” Spencer said. Mavis went to orientation and loved college so much that she went back the following year. She would go nearly every week to ride in Florida.

“It was obviously an agonizing thing for her,” Spencer said. She flew back to Florida to compete and work as a groom several weekends very month. It became too much work. So, after a year and a half, Spencer and Woodard gave her their blessing to return to horses full time.

Spencer said he would not be surprised if she went back to finish her degree in English and comparative literature. In addition to loving horses, Mavis loves Shakespeare and writing.

“Nothing that Mavis decides to do with her life would surprise me except sitting on a couch and eating bonbons,” Spencer said.

“I could see her commitment and see that she was on her way,” Woodard said. “The thing that we both believe about human beings is that we come into this world who we are. As a parent you have to understand that they are not a reflection of you. They are another human being, and you have to give them the respect they deserve. Your responsibility as a parent is to look at them and see who they are and then expose them to as much as you possibly can and let them fly.”

The pathway to success

Mavis riding as a top-ranked Grand Prix Competitor.

Mavis was able to juggle Columbia and working for Farrington. She even traveled to Europe with him to care for his horses at major shows. It was important exposure. After that, she worked for Darragh Kenny, another top-ranked Grand Prix competitor, at his training facility in Florida as his head groom.

Over the years, the work as a groom provided an in-depth education in horse management and care. In 2014, Mavis worked as a groom for Lorenzo de Luca, a rider with Neil Jones, who she had interned with in 2008. When Mavis groomed for de Luca at the Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games in France that year, she got her chance to return to the saddle.

De Luca got injured and told Mavis to take over riding his horses, opening the door for her to put aside hoof picks and return to the show ring as a rider for one of the top horse trainers in the world.

“I remember walking into the barn one day and seeing the list on the board for a training show. I had six Grand Prix horses under my name,” Mavis said. It was a surreal experience to go from grooming to suddenly having five-star Grand Prix horses to ride and compete. The shows went well, and Jones asked her to start riding on a regular basis for him.

The plan was for Mavis to ride the younger horses while de Luca mastered the more experienced Grand Prix horses. But then in December 2014, de Luca got a job riding for another stable, and Mavis was suddenly moved up to Jones’ top rider.

“Mavis is the exception rather than the rule,” said Jones, recalling how even as a 16-year-old intern she always wanted to get her hands dirty grooming horses rather than have someone else take care of her horse like other competitors. “Everyone knew she had talent, and then when Lorenzo got hurt, they could really see it.”

Horses have a way of knowing the humans who understand them. They have an uncanny way of looking at the people with “the touch.” Call it a horse whisperer. Call it a knack. But it is evident to the people who surround Mavis Spencer that she has “the touch.”

About a decade ago, the Spencer family attended a wedding at a dude ranch in Montana. By the second day, the horses in the corral would look at her in a knowing way, a way that was noticeably different to everyone on the ranch — ranch hands and guests alike. It was like she had a halo over her head. “She would come up to the corral, and the horses would turn and look at her like, ‘there’s one,’ ” Spencer said. Seeing that it was special, the ranch hands told Mavis to go select any horse that she wanted to ride every day.

“I think horses recognize people like that,” Spencer said. “Horses can smell and see the difference between people who understand them and amateurs and experts who are full of it. It doesn’t surprise me that they would look at her. Horses choose their people.”