The notion of melancholy – in an era where we tend to prioritize positivity, enthusiasm, and constant self-improvement – could be perceived as merely excessive and self-indulgent. The consequences of non-compliance with society’s demand for ceaseless productivity appear to contradict any inherent value in a sentiment that seems to only invite apathy and sadness.

Nevertheless, throughout history, numerous scholars and artists have not only declared melancholy the source of their ingenuity, they also have linked it to profound creative resourcefulness that yields existential answers, with philosopher Søren Kierkegaard even referring to it as his closest confidante. The link between creative ingenuity and melancholy throughout cultural history traces mankind’s search for meaning in the face of despair and the answers it yields.

The History of Melancholy

The word melancholia or melancholy originated from the Greek melaina chole, which means black bile. It’s a word found throughout ancient, medieval, and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by a markedly depressed mood, bodily complaints, and sometimes hallucinations and delusions. Melancholy was regarded as one of the four temperaments matching the four humours; at the time, disease or ailment was believed to be caused by an imbalance in one or more of the four basic bodily liquids or humours.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) once wrote that melancholy was a complex condition that could be caused by a variety of factors, including genetics, environment, and diet. He believed that many of history’s greatest artists, writers, and thinkers were prone to melancholy and that this condition played a significant role in their creative output, making it a necessary condition for creative genius. It allowed people to see the world in a different way, and to explore complex emotions and ideas in ways that were not possible for those who did not experience states of melancholy.

The Aristotelian principle that genius and melancholy were linked perfectly suited the ideals of Renaissance humanism and the melancholic figure – immortalized in Albrecht Dürer’s famous engraving Melencolia I (above) and often depicted as lost in thought and withdrawn. It served as an allegory to convey complex states of contemplation.

Melancholia, also known as acedia in medieval times, eventually became regarded as a valuable emotion that could foster artistic expression and creativity. In the age of Queen Elizabeth I, it was deemed not only fashionable but also very masculine to fall into despair facing the state of the world. Being melancholic as a result of this despair was seen as proof of high intellect, seriousness, and nobility. Other nations used to refer to male melancholy as “the English malady” or “the Elizabethan malady,” and although it was often deemed a grave illness, melancholic tendencies became a desirable, romantic disposition for young men. The melancholy man, known to contemporaries as a “malcontent,” is epitomized by Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet, the “Melancholy Dane.”

During the late 16th and early 17th centuries this culminated in what could be called a cultural and literary cult of melancholia, and the former calamitous affliction was now fully transformed into the mark of genius. Eventually, the attitudes of melancholy became an indispensable adjunct to all those with artistic or intellectual pretensions.

Though not under the same name, a similar phenomenon occurred during the German Sturm und Drang movement, with such works as The Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe. Early 19th century Romanticism expressed similar sentiments with Ode on Melancholy by John Keats and the coinage of the term Weltschmerz. Symbolism followed suit with Isle of the Dead by Arnold Böcklin.

In the 20th century, much of the counterculture of modernism was fueled by comparable alienation and a sense of purposelessness called anomie, and it was during the late 20th century here that melancholia lost its attachment to genius and intellectual probing and in common usage became entirely a synonym for depression.

Melancholy in Art

Perhaps the most famous interpretation of melancholia was engraved by Albrecht Dürer at a time when the visual arts were undergoing a revision in status during the Renaissance by incorporating mathematics and complex geometry, which offered an intellectual system to rationalize beauty.

In the engraving Melencolia I, the winged figure sitting with her head in her hand personifies that new generation of artists fueled by scientific rigor and equipped with geometric and mathematical knowledge. The little putto inscribing a tablet with a grindstone as a symbol of manual labor contrasts directly with the truncated rhombohedron next to it, and so do the carpentry tools of the craftsman that seem to lie discarded in favor of the learned application of geometry next to the sphere in the lower-left corner.

Scholars commonly describe the image as a self-portrait where Dürer declares his melancholic despondency, with the personification of melancholia waiting for inspiration to strike and stymied by intellectual inactivity, representing the pervasive emotional state of the creative individual filled with internal conflicts.

French painter Paul Gauguin’s 1891 painting Faaturuma (below), which loosely translates from Tahitian as melancholic, encapsulates a different aspect. Similar to his Te Faaturuma (The Brooding Woman), Gauguin interprets melancholy as an aesthetic emotion and a deeply ambivalent state uniting conflicting emotions evoked by both the beauty and the sorrow over something lost. An introspective young woman is pictured in her chair, head inclined slightly forward and to the side. She appears to have no outward expression on her face, and her closest eyebrow is slightly arched. Her hands are placed stationary on her lap and armrest, and there appears to be a subtle rocking motion of the chair off the floor, denoting reflection or wistfulness.

Gauguin was fascinated by the silence and melancholic nature he encountered in Tahitian women. In popular travel accounts, these women were portrayed as being nostalgic for their native culture, which had seemingly diminished with advancing civilization controlled by the church and Western society.

In Gauguin’s portrait of a woman wearing many layers of missionary gowns, along with her wedding ring, the artist implied an archetype who lamented her present life in a Europeanized society and longingly yearned for earlier days of freedom. The figure of the indigenous Polynesian woman was commonly depicted by Gauguin as a representation of colonialism’s cruel legacy. In this way, he captured the emotive symbolism of imperial power and its consequences and their melancholy as a metaphor for the inherent losses wrought by the colonial world.

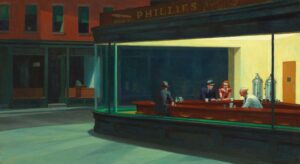

In the work of Edward Hopper, loneliness and melancholy are prevalent themes as well. His paintings often feature solitary figures in urban or rural settings, emphasizing their isolation and disconnection from society. In Nighthawks, four figures sit alone at a diner late at night, seemingly lost in their thoughts. Similarly, Office in a Small City shows a man working alone in a dimly lit office building. Hopper’s use of intense lighting and stark compositions further highlights this sense of melancholic solitude, making his paintings hauntingly beautiful and deeply emotional, while epitomizing human loneliness in the modern urban landscape, social alienation, and an all-encompassing feeling of meaninglessness.

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1952

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1952

A Melancholy Society

For many, the complexity of melancholy as a state of solitary introspection and intellectual anticipation as well as a source of artistic inspiration holds a fascination in itself and suggests the further thought that it may be considered an aesthetic emotion per se.

Or as the famous philosopher Søren Kierkegaard described it:

“Besides my other numerous circle of acquaintances, I have one more intimate confidant – my melancholy. In the midst of my joy, in the midst of my work, she waves to me and calls me to one side, even though physically I stay put. My melancholy is the most faithful mistress I have known; what wonder, then, that I love her in return.”

Many philosophers would argue that it is through the voluntary state of melancholia that the ego and our self-deception collide with the inalienable truth of existence where we fully realize the human condition. This is where the greatest artists, poets, and thinkers in human history found their deepest wells of inspiration.

Many philosophical schools, including Stoicism, believe that suffering, loss and disappointment are core parts of our universal human experience, and the more we mask these existential maxims through material attachment, distractions and consumerism, the more we are haunted by those inevitable realities. The way we deal with the truisms of the human condition as a society, with human suffering and our daily struggles, with deep sorrow and grief as well as our mortality and that of our loved ones, is at the core of what defines us as a culture. It could therefore be argued that our modern denigration of melancholia as unproductive apathy and depression merely masks a deep feeling of inadequacy in the face of existential threats to our convenience-driven way of life.

Yet denying ourselves this inconvenient and painful confrontation through melancholic introspection by turning even our meditation practices into spurts of self-improvement, or mere recreational breaks from productivity, means denying ourselves experiencing our mind at its full capacity.

What the cultural significance of melancholy teaches us is that the true fortitude and resourcefulness of the human spirit are revealed only when we allow the walls of our materially attached and carefully constructed personas to be stripped away and experience our existence at its most raw and vulnerable. The art of introspection through melancholy is therefore to be able to sustain this state without falling into the abyss of depression and existential despair while reaping its creative and intellectual rewards and gaining a source of strength and creative inspiration untainted by personal and material attachment. This is what marks the true resilience of the human spirit and its unwavering pursuit of meaning – truth and beauty despite the chaos and constant fragmentation of a world that seems to be constantly coming apart at its seams.