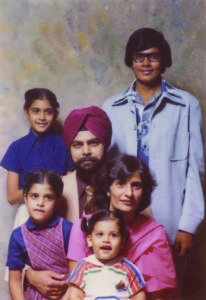

With a family name that denotes strength and humility, Nikki Haley discovered early on how to push through her fears and find comfort in being the only woman standing. Born Nimrata Nikki Randhawa, she experienced racism firsthand as the only Indian family in rural South Carolina in the ‘70s. Her mother used this opportunity to imbue in Nikki a lesson that forever guided her in life: if you can focus on your similarities rather than differences, then you can open minds to enact real change.

This lesson, coupled with an unwavering passion to fight for those who cannot fight for themselves, swiftly carried Nikki to the political stage. In 2004, she became the first Indian-American to hold office in South Carolina, and in 2010, she became the first woman to serve as governor in the state, as well as the youngest governor in the country. Following her governorship, she was selected in 2017 to serve as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. No matter the role, Nikki is always fulfilling her purpose by making a difference for the people, the state, and the country she serves.

What prompted your parents to leave India, reside in Canada and then relocate permanently to the United States?

My mom was a lawyer in India and one of the first female judges nominated to serve on the bench. At that time, it was hard for women to hold those types of positions; you just didn’t see women on the bench. I think that the family members decided that it was not safe for her. And so, while she really wanted to, they didn’t allow her to do it. She was a trailblazer, really, but they just didn’t think she would be adequately protected, and they didn’t want to take any chances. My father had completed graduate school and wanted to get his PhD. When he was offered that opportunity at the University of British Columbia, they packed up and moved to Canada.

Your father’s given name is Ajit Singh Randhawa. What does Singh mean?

Singh is associated with the Sikh religion. When an Indian man is given the middle name Singh, it has a cultural and a religious connotation. Anytime someone of the Sikh faith has Singh in his or her name, then it defines him or her.

Singh also connotes a warrior and a lion?

Yes. Sikhs are known to be tough, loyal, strong and good fighters.

Are those qualities you share… a part of who you are?

I am very much a part of my parents. My dad taught me strength and grace, and my mom taught me unbelievable willpower. The two of them geared me to be who I am and what I continue to be.

Four children. What number are you, and where were you born, respectively?

I am number three. My oldest brother was born in India. My sister was born in Canada. My little brother and I were born in South Carolina.

Today, India is facing the horrors of Covid-19, leading the world in deaths. With your worldview, what can you share with us?

Sadness. The one thing about India is it is an amazing democracy. They elect their leaders and have freedoms that you want to see in an Asian country. I think the thing that is so sad is that when so many people are in such a confined space, the results are more severe. What we have experienced here in America is daunting. Losing 3000 people in one day in India just hurts. I know that is the case for my parents, as well. I have talked to them about it, and I see the sadness in them. When you think of your birthplace, you never want to think of suffering. It always tugs a little bit at their hearts.

Isn’t pain universal?

Yes. When you look at shootings and movements like Black Lives Matter, I think people don’t get what is at the heart of the emotion: that it hurts to see something happen to someone that looks like you, right?

It is a real, deep thing. So, when somebody sees a total stranger get hurt, if that person looks like you, you can relate. After 9/11, it was scary for my dad to just be in his car or go to the gas station because he wears a turban. He put a flag on the back of his car just to show people he was American. He did that for his safety. I remember there was a gas station owner, and I think it was in Wisconsin, and he wore a turban. People went in there and beat him. I felt such pain because he looked like my dad, and it was like my dad. I am very sensitive when people feel racial pain. At its core, I believe it is because they can identify with those people that look like them. Therefore, in India when we see the devastation of Covid-19, I think it is painful for my parents.

Who is your greatest mentor?

Definitely my mom, because she was my only female example of incredible strength. Growing up, I didn’t see a lot of strong women. My mom came from a very wealthy lifestyle. In Canada, my parents started all over with $8 in their pocket. My mom worked three jobs. She was taking care of a disabled child, working at the post office United States, my dad got a job as a professor. My mom needed a job, so she taught sixth grade social studies. Because she was missing being at home, she decided to start a small business that she would open after school. She sold products from India. At first, she sold them out of the living room of our home, and then she expanded it into an office space. I watched as she turned that tiny little office space into a bigger store. She added on clothing, and then she added on accessories. Before we knew it, a 10,000 square foot store was doing extremely well. She just never stopped at being persistent.

Did she work from dawn until dusk?

She always worked. Both of my parents always worked. They had a want and a drive to make sure that their children had a better life than they did. Everything they did was for us. They always worked and were always creative. They did this against a backdrop of not having it easy. It was a tough time to go through, the late sixties, early seventies, in South Carolina, in a rural town. They were doing things without a lot of help. They didn’t have a lot of friends. They were the only Indian family in that town. So it was not easy, but they just were so determined.

Do you think that leadership is easy?

No.

What lessons did you learn from watching them toil every single day to build a better life for you and your siblings?

If something didn’t work, they just kept going. They kept trying; they never stopped. They never saw boundaries in anything that they did. My mom did not know anything about American clothes. She did not know what a girdle was, but after 30 years, she owned one of the top high-end women’s stores in the state. It was one of those things. She just was determined to learn. They never have stopped learning. They understood that if you didn’t know how to do something, you went and figured out how to do it. You read something else, or you saw something else or you found someone else. They also thought that education was the key to everything.

Your mother and father have always been supportive of you. At some point, they became your village. Tell me about that.

Interestingly, Indian families always want their children to become a doctor, lawyer or engineer. I clearly didn’t become one. While my sister was fascinated by the business and my brothers were doing their own thing, my mother wanted me to stay close to home and close to the family. In the store, she saw me wandering around, not interested in the clothes, gifts or merchandise, like my sister. Our bookkeeper was leaving. She had given my mom notice, and we had not found anybody else to fill that position. One day, she said, “I’m really getting worried. We’re running out of time. You need to hire someone.” I happened to be walking by, and my mom literally grabbed my arm and said, “Train her.”

The bookkeeper said, “Raj, I can’t do that. She is 13 years old.” My mom responded, “If you teach her, she will do it.” That is how and when I found my love of numbers. She taught me how to do everything financial. I was doing the deposits, cutting the checks and deciding what we paid. I was looking at all of those things. From that experience, I learned the value of a dollar. When times were tough, we stretched, and we had to prioritize. When times were good, we didn’t celebrate because we knew that there would be tough times again. I loved numbers because numbers tell a story. If they don’t tell the story you want, you figure out how to make those numbers different. It was a love that I found.

Rural Bamberg, South Carolina. What age were you the first time you realized that there was an undercurrent of racism?

Five.

And tell me about that?

It wasn’t until I went to school that I felt it. Remember, we were the only Indian family in town. I always say we weren’t white enough to be White. We weren’t black enough to be Black. I knew we were different because my dad wore a turban. At the time, my mom was wearing a sari, and no one else was. I saw the looks that we got. At five, I would be teased on the playground for being Brown, and I would go home and tell my mom. My mom would say, “Your job is not to show them how you’re different. Your job is to show them how you’re similar.” It is actually amazing how that lesson on the playground has played out throughout my life. Whether in the corporate world, as governor, as ambassador, when you see challenges, if you first talk about what you have in common, people let their guard down, and then you can take on the solution. Every time I have had a challenge or a road bump, I define what we had in common and show people in what ways we are similar. It sounds like a small lesson, but it was actually a big lesson in life for me.

Is that core to your success as UN Ambassador, this idea of finding a common ground and then mitigating the periphery?

Yes. When I had to negotiate North Korea, I thought, how do you negotiate with the Chinese that don’t want to do it? How do you get the other countries to come along with the Chinese? What I did was I said first, you have to understand their fears. I always think you have to understand your opponent’s fears. I knew what they were; they were worried about two things. They were worried about war on the peninsula. And they were worried that if the Kim regime fell, all those North Koreans would go into China, and they didn’t want that. So, after I understood their fears, I started talking to them about how we were similar. We didn’t want war. We, too, didn’t want regime change. We wanted to make sure that those things weren’t going to happen. We knew that if we could get North Korea to stop testing ballistic missiles, the world would be safer. So, when we could talk about the core issues, we could start drilling down into the “how.”

Many lessons came from your childhood. Tell me about “the pageant.”

My sister first told the story about the pageant. At the time, parents put their child in the Little Miss Bamberg pageant. It was a big event for a town of 2,500. Someone told my mom she should put her girls in the pageant, so she put both of us in. At the time, they had a Black queen, and they had a White queen, so they took my parents to the side. They disqualified us because they didn’t know which category to put us in. They felt if they put us in the White category, then the White families would be mad. If they put us in the Black category, then the Black families would be mad. Instead, they disqualified us. My mom said, “She has been practicing her song” (because there was a talent component), “Can she at least sing her song?” My song was, This Land is Your Land, This Land is My Land. I sang, they gave me a beach ball, and they sent us on our way. I never did another pageant after that, by the way.

Do you think that your experiences gave you a sensitivity to the rawness of the racial tensions in our country?

Yes, very much so.

Removing the Confederate flag from the state capital was under your watch as governor. Tell me how that interplayed with the Mother Emanuel AME Church massacre.

When I came into office, I was interested in whether we could bring down the Confederate flag for multiple reasons. The NCAA wasn’t allowing us to have tournaments and was not opening up the state. I actually spoke to some prominent Republicans and Democrats that had been in South Carolina during the last battle to bring down the flag back in 2000. The Black Democrats and the White Republicans both said, “Don’t go there.” They saw how hateful it was, and they didn’t want to relive that. They remembered the days of security, people hating each other. We also needed a two-thirds vote to bring it down, making it almost impossible, if there was no will, so we left it alone. No one ever really brought it up.

With the church shooting, even then that was not my first instinct. We had just had a shooting, and it was the first shooting in a place of worship. I thought, no child is ever going to be safe going to church again if something like this could happen. If you can have 12 people go to Bible study on a Wednesday night, this could happen. I’ll never get over the fact that on that night, someone showed up that didn’t look like them, didn’t sound like them, didn’t act like them. They didn’t throw him out, and they didn’t call the cops. Instead, they pulled up a chair and prayed with him for an hour. Think about that. As they bowed their heads in the last prayer, he began to shoot. People like Ethel Lance who had lost her daughter two years prior to breast cancer and had a broken heart. She would go around Mother Emanuel Church, cleaning the church, singing “One day at a time. Sweet Jesus. That’s all I ask of you. Give me the strength to do every day what I have to do.” Tywanza Sanders, our youngest victim, had just graduated college and had the whole world in front of him. On that night, he stood in front of his 87-year-old great aunt Susie and said, “You don’t have to do this. We mean no harm to you.” Or it was people like Cynthia Hurd whose life motto was simply to be kinder than necessary. That’s who these people were. They loved their family and loved their church. They loved their community. When this happened, the whole state was in shock. Two days later, in his manifesto, the killer held up the Confederate flag. That was it. The national media zoomed in wanting to define this state. They wanted to talk about racism in South Carolina, they wanted to talk about the death penalty, they wanted to talk about gun violence. I remember at the time strong-arming them saying, “We have nine funerals. There will be a time and place where we talk about this, but it is not now.” Then the manifesto came out. I knew something had to happen. Michael had been on military duty, and it had been an upsetting few days. I remember texting him saying, “I have got so much in my head. I need to talk to you.” When he came home, I told him that I thought that we had to try and bring the Confederate flag down, and he said, “Then do it.” I brought my staff in, and I said, “I want to have four meetings on Monday. Don’t tell them what this meeting is about because I know they won’t show up. I want to meet with lead Republicans, lead Democrats, the federal delegation and community leaders.” When they came into that office in each one of those meetings, I said, “At three o’clock today, I’m going to call for the Confederate flag to come down. If you will stand with me, I will forever be grateful. And if you won’t, I won’t tell anyone you were ever in this room.”

I had my husband with me that day because I thought he was going to be the only one standing with me. But we had Blacks, we had Whites, we had Republicans, we had Democrats, and they stood together. We said, it’s time. Half of the state, when they saw the Confederate flag, saw it as heritage, as ancestry and as patriotism. The other half of the state saw it as hate. My job wasn’t to judge either side. My job was to carry them to the next level. My job was to say, “How do we get us to a better place?” If I had judged either side, none of it would have worked. And then we had to get a two-thirds vote.

Did you know you would get a two-thirds vote?

I knew we had to get a two-thirds vote. I knew that there was no way we could not get it, or the whole state would fall apart. It was a tough fight. It was right after Ferguson so trying to hold the state together was hard. However, we did it by reminding people of the goodness that we have in us and not letting the country define us. The Senate was actually easy because they had just lost their brother, Senator Clementa Pinckney, who was one of them. You couldn’t stand in that chamber and not see the black drape over the desk and the red rose on there and not be moved by it. The house was very hard.

There was tremendous leadership that came from that experience.

Yes. It brought out the biggest passion in everyone. At the end of the day, the passion that mattered the most were the people of South Carolina. We didn’t have protests; we had vigils. We didn’t have riots; we had hugs. The people of South Carolina stepped up in a way that truly is extraordinary. We saw that flag come down.

If you look back at your service as governor, was that a defining moment, your legacy?

I don’t think that defined my legacy though people have talked about the Confederate flag coming down as a legacy. During my time as governor, we had a hurricane, a thousand-year flood, a school shooting and a church shooting. There were so many tragedies throughout my tenure. When you are leading, your goal is to protect the people and move them as much as you can. I think that people like to look at the Confederate flag as a movement forward. It brings me some sadness because I think that moment belongs to those families because they were able to forgive a killer. They were able to move on in a remarkable way. I want the spotlight to be upon them because they truly were the heroes. Our state might have fallen apart had they gotten angry or said angry words, but they chose grace.

You have commented that Africa has both tremendous potential and opportunity, but also is a real threat to world stability. Do you still believe that?

I do. I never went to the pretty places, those places where the other cabinet members went. The places I went were the opposite, and you learn so much in these places. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, they use rape as a weapon of war. In South Sudan, I sat with crying mothers whose babies were literally taken from their arms and thrown into fires right in front of them. When you hear those stories, you see how desperately they want elections, and you see how desperately they want education for their kids. You look at those populations and know if something doesn’t change, those young children will grow up to be angry and resentful. The only thing worse than angry and resentful is uneducated because that is what leads to terrorism and causes problems in the world.

I am worried about what is going to happen to Africa. There are so many opportunities there. They desperately want to have free and fair elections, and they desperately want to have more. It is my hope and prayer that they get there. I think America always has to keep its eyes on Africa for opportunity purposes, but also for safety purposes.

South Sudan was particularly difficult for you to visit. What happened when you boarded the plane to depart?

There are so many challenges, like not having clean drinking water or having girls confined—they can’t leave the camp because they will get raped—or having boys that are literally taken to be child soldiers. There was one story I was told where two brothers were abducted and taken to be child soldiers. Their mother was kidnapped, they put her on a tree, and they raped her in front of the boys. Then they gave each of the boys a gun and told them to shoot, and they had to keep shooting her until she died. It was their way of disconnecting these children emotionally from their family. When you hear those types of horrors, can you imagine all the trauma these kids have gone through? We would go to these camps, hear these stories and find out what had happened. Then you see these kids, and they have the happiest faces. They don’t know what they don’t have. When I boarded the plane to leave, there was such sadness because you wanted to help them. You realize your job is not done. You feel like there is more that could be done. And so, it is hard.

AMRITSAR, INDIA – NOVEMBER 15: South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley looks at a picture of the martyrs at Jallianwala Bagh on November 15, 2014 in Amritsar, India. Haley said she wanted to promote business ties between her state and Indian companies. “India is my second home. Attracting investments from overseas companies is my job, but building business ties with Indian companies is my personal desire”, she said. (Photo by Sameer Sehgal/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

How do you reconcile that? We are sitting here in one of the most privileged areas of the world, and we both acknowledge gratitude and blessings, but how do you reconcile the horrors of the world and what you’ve seen?

You never forget the faces. You never forget the voices. You never forget the stories. They haunt you always because there is more that has to be done.

How do you do more?

Tell their stories. When you are in government, you push policy, right? So, we pushed for better peacekeeping operations. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, we pushed for another election because the leader wasn’t leaving. We returned a couple of times to make that happen in South Sudan. We met with the president, and I showed him pictures of children. I said, “Look at these kids. You never leave this palace to see these kids, but they know you. And they’re looking to you to give them a better life.”

You have a gift of building teams, something noteworthy early in your career. How do you find philosophical alignment and then retain loyalty?

Part of it is gut. When I look at someone as a team member, I am looking at who would be a good partner on the team to make sure that we can all work together. You want knowledge, you want skill, but those are the easy things. The trust, the loyalty and your gut feeling are what matters at the end of the day. You also want team members you can grow because you want to grow as a team. You don’t want to have the perfect team but the ability to grow into a better team. Chemistry and making sure that the skills and experience complement each other are critical. I think having people who understand trust and loyalty and what it means to grow together and have each other’s back has always been very important to me. My team is everything. I am only as good as the team that I have around me, which means the team has to be able to tell me when I’m right and tell me when I’m wrong. They must also be able to understand that we have to be flexible as we move forward. I invest a lot in our team.

All leaders experience team members and partners that exit. How do you deal with that?

Well, it does happen. You have people that for some reason or another move on or part ways. It always is painful because my team is my family. I very much look at them like family. I love them. I care about them in good times and bad times. So anytime you have that it is painful, but then we also keep track of everyone. Team Haley has grown from this tiny little group to a much bigger group. Those that were in my first governor’s race know if they ever need anything, they can look to the team at the UN and any cross alignment. They all know to help each other. It’s like our own little network of helping each other. That Is what I want for them.

How big is your Team Haley today, and where do they reside?

15 people and they are all over the country.

Is this a result of the new norm due to Covid-19?

We had an office in New York where we were all congregating. During Covid-19, everybody worked from home, so they dispersed from New York. Some went to Florida, DC, Maryland and South Carolina. We all just work by Zoom, but we also meet once a month. Now, we have moved the offices to DC where a lot are congregated. Covid-19 changed the way we do business

You wrote, “I never understood the fear that many diplomats have about being isolated. My view was, and still is, if your position is right, you should not be ashamed of it. You should be proud to stand alone within it if you must.” You’ve taken many “alone” steps in your life. Where does that come from?

Usually fighting for other people. The times I stand alone are when people are depending on me. It is what gives me the strength to do it. I know there is a greater good and a bigger story. It is not that you seek these moments out, but when they present themselves, you have to fight for others. You have to push the ball forward.

Do you have fear and, if so, around what?

I do have fear. Everybody has the fear of failure, the fear of letting people down, the fear of not being able to accomplish what needs to be accomplished. But the one thing I learned early on, the lesson I tell every young person I see, is to learn how to push through the fear. If I didn’t push through the fear, I never would have run for office, in a primary for the state house, against a 30-year incumbent. If I didn’t push through the fear, I wouldn’t have become governor. If I didn’t push through the fear, I wouldn’t have taken the job as UN ambassador. You have to be willing to push through the fear because when you do that, you learn what it’s like to live life. If you don’t push through the fear, you never know what could have been.

You have witnessed tremendous atrocities, abject poverty, forgiveness and opulence. How do you calibrate and remain balanced?

You count your blessings. I wake up every morning and thank God for life. I go to bed every night, thanking God for the smallest, to the biggest things of that day. The only way you get through it is by counting your blessings and being as humble as you possibly can. To know that your job is to make other people’s lives better in whatever way you can, you must do that.

Is it a conscious practice of humility or is it a part of who you are naturally?

I think I’ve always been like that. My full name is Nimrata Nikki Randhawa. Nikki, my middle name, means “humble little one.” My parents taught me that humility. I had everything I needed in life, but I felt life around me. I think when you come from tough circumstances, the challenges are always hard. When you feel that, it makes you humble because you never forget what that five-year-old girl felt like. It also reminds you that you never want anyone else to feel that feeling. I ended up fighting for people who I think can’t fight for themselves. I end up trying to keep people from having pain because I know what that pain felt like. I think that is the reason that I am humble. I always remind myself to stay humble.

How do you clear your head amidst the chatter?

Sitting outside makes life feel not so hard. If I listen to music, it takes me away.

You wrote, “At every point in my life, I’ve noticed that if you speak your mind and you’re strong about it, a small percentage of people will resent you. The way they deal with their resentment is to throw charges at your lives to see what sticks. And they do this to diminish you. Women especially have been dealing with this for a long time.” Why is that?

I don’t know why it is. I stopped trying to figure out the why and just have accepted that it will happen and that it does happen. I think it’s easier if you don’t complain about it, and you just expect it, and you fight through it.

What’s the antidote?

To keep working. You are never going to please people all the time, or you are not moving the ball. There will always be a percentage of people that don’t like me and don’t like what I stand for. They don’t like how I do things or find me to be a threat in some way, shape or form. I can’t worry about that. I just keep my head down and keep working.

AMRITSAR, INDIA – NOVEMBER 15: South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley along with her husband Michael Haley paying obeisance at Golden Temple on November 15, 2014 in Amritsar, India. (Photo by Sameer Sehgal/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

You’ve been described as both a disruptor and now as a change agent. Is that the same thing?

I think a disruptor is one that when you see something wrong, you say it and you blow it up. I think I have always been that. Change agent is the other side of the disruptor; you first blow it up, and then you change it and fix it, and you make it better. I believe they go hand in hand.

Politics aside, what is your legacy?

I hope that people look at whatever I touched or whatever I did, and know I did the best job that I could do, and that people were better for it. I hope that people can feel like my being there made a better place for them. Whether that’s a better country, a better world, just a better state . . . that people felt that everything I touched made a difference.

If you had a choice of being in corporate America, on the world stage, in a secondary/supportive role or philanthropy, what would you choose?

I want to lift people up. That is where I get my motivation. Anything that I can do that can lift people up and make a difference, to me, is moving the ball. Moving the ball doesn’t mean winning either. Moving the ball happens when other people benefit because you were there.

What is your avatar, your life focus here forward?

People. If I am around children with our education foundation, then I’m focused on those kids. If I am in South Sudan and I see those mothers, then I’m focused on those moms. I focus on whatever is in front of me. I soak it in. I love to see how small businesses make things work. I love to see what people care about. I feel the pain of other people deeply, and I want to stop their pain. If there is something I can fix, I want to do it. I have very little patience for things that can be changed to better others and are not.

Give your younger self a word of wisdom or a piece of advice that might have helped you in some way.

I think I would have just said, “It’s going to be okay.” It was always hard, and it was always scary, but that piece of advice would be the one thing that would have helped me, just to know it was going to be okay.

If you could ask God a question, what would that one question be?

That’s a tough one, but what is my purpose?

Nimrata Nikki Randhawa “humble little one” and Nikki Haley “loyal, strong and warrior-like,” I believe you know that purpose.