JOHANNA MANSFIELD SULLIVAN was born to Irish immigrant parents in Agawam, Massachusetts on April 14, 1866, a year to the day after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the end of the Civil War. When she was five years old, she contracted trachoma, a painful bacterial infection that attacks the cornea of the eye and if untreated, led to blindness—as it almost always did in those days before antibiotics. Johanna was eight years old when her mother died. Her alcoholic father abandoned the girl and her two siblings, a younger sister, Mary, and their little brother Jimmie. Four months later, Jimmie died of consumption. Mary was sent to live with an aunt and no more was heard of her.

With no one and nowhere to go, Johanna was sent to an almshouse (poorhouse), where she was subjected to deprivation and cruelty beyond measure. In 1877, at the age of 11, she underwent a third eye operation, at a charity hospital in Lowell, Massachusetts called Soeurs de la Charite. As with the previous two, it was unsuccessful in restoring her sight or easing the pain. Johanna remained at the almshouse until 1880 when she had a chance encounter with Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, State Inspector of Charities, who subsequently would gain recognition as a social reformer, teacher, and founder of the American Social Science Association. Annie fell upon his sympathy and begged him to remove her from the evil place, where reports of sexually perverted practices and cannibalism ran rampant. Sanborn took pity on the child and arranged for her to be sent to learn and live at the Perkins School for the Blind. She matriculated on October 7, 1880.

🙦

THE PERKINS SCHOOL FOR THE BLIND was founded in 1829 in Watertown, Massachusetts by Samuel Gridley Howe, a specialist in blindness who had studied extensively in Europe. The school quickly garnered worldwide recognition for its groundbreaking work on educating the blind; indeed, when English writer Charles Dickens came to America in 1842 on a lecture tour, he asked to visit the Perkins School, which he documented in his book, American Notes. (NOTE: The Perkins School is the oldest school for the blind and its mighty work continues to this day, partnering with schools, universities, government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and parent networks in 67 countries to empower the blind and visually impaired to surmount their disability and embrace their strengths.)

Johanna was a rough child, unkempt and ignorant of social skills having grown up in the School of Hard Knocks at the poorhouse. When she arrived at the Perkins School, her uncivilized ways set her apart from the other students, who had come from refined families, and her coarse behavior subjected her to humiliation and bullying by her peers. Seeing this, some few kind teachers took the deprived and secretly terrified girl under their care. They saw something shining in her. Johanna soon rewarded their kindness by working hard to improve herself. An attentive and willing student, she was hungry for knowledge. While at Perkins, she endured more surgery, and though she would never regain her sight completely, this time the operation worked. She earned the respect of teachers, students, and administrators alike, and in June 1886, at the age of 20, Johanna graduated valedictorian of her class.

Johanna was a rough child, unkempt and ignorant of social skills having grown up in the School of Hard Knocks at the poorhouse. When she arrived at the Perkins School, her uncivilized ways set her apart from the other students, who had come from refined families, and her coarse behavior subjected her to humiliation and bullying by her peers. Seeing this, some few kind teachers took the deprived and secretly terrified girl under their care. They saw something shining in her. Johanna soon rewarded their kindness by working hard to improve herself. An attentive and willing student, she was hungry for knowledge. While at Perkins, she endured more surgery, and though she would never regain her sight completely, this time the operation worked. She earned the respect of teachers, students, and administrators alike, and in June 1886, at the age of 20, Johanna graduated valedictorian of her class.

“Fellow-graduates,” she addressed the gathering. “Duty bids us go forth into active life. Let us go cheerfully, hopefully, and earnestly, and set ourselves to find our especial part. When we have found it, willingly and faithfully perform it; for every obstacle we overcome, every success we achieve tends to bring man closer to God and make life more as He would have it.”

After graduation, Johanna became a tutor at the Perkins School, unaware that her life would soon change. The following summer, the school’s director, Dr. Michael Anagnos, received a letter from a gentleman in Tuscumbia, Alabama who had been referred to him by a mutual friend, Dr. Alexander Graham Bell. The writer was a former captain in the Confederate Army whose plantation, incredibly, survived the destruction of the War. He and his wife had a seven-year-old daughter who, when she was 19-months-old, contracted an undiagnosed disease that left her totally deaf and blind.

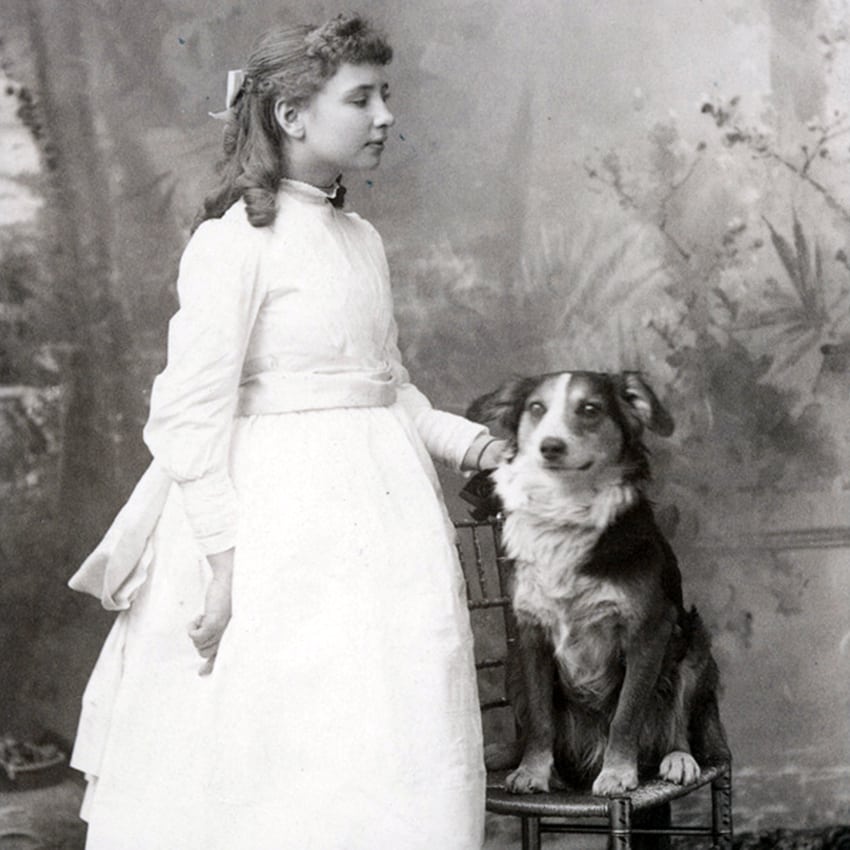

Young Helen

In his letter, the captain explained his daughter had no way to communicate and despite their efforts, behaved like a rabid wild animal—destructive, angry, shoveling food into her mouth with her hands. He wanted to institutionalize the youngster but his gentle wife, Mary, couldn’t bear the thought of separation. Things clearly could not continue after the youngster got into a jealous rage and toppled over her baby sister’s crib. Miraculously, the infant, though frightened, was unscathed—but that was the final straw.

Dr. Anagnos summoned Johanna and with her consent, replied to the captain immediately. On March 3, 1887, “Annie,” as she was called, arrived at the home of Captain and Mrs. Arthur Keller to assume the position of teacher to their unfortunate daughter, Helen.

Dr. Anagnos summoned Johanna and with her consent, replied to the captain immediately. On March 3, 1887, “Annie,” as she was called, arrived at the home of Captain and Mrs. Arthur Keller to assume the position of teacher to their unfortunate daughter, Helen.

Annie soon saw a pattern to Helen’s behavior and realized she would have to remove her student from her familiar environment and start with a clean slate. Despite Mary’s protestations, Annie and Helen moved into a cottage on the Keller’s Alabama plantation, a short distance from the big house. They were driven by horse-drawn carriage by a long and circuitous route to give Helen the impression that were traveling far from home. When they finally arrived at the cottage, Helen was confused by the unfamiliar place and suffered anxiety at being separated from her mother. Annie, who was of slight build, had to physically struggle to control Helen from angrily throwing objects and running away.

Immediately Annie began teaching Helen the Perkins School techniques developed by Samuel Gridley Howe, but these did not work. In light of such a challenge, Annie devised her own approach. She would spell words in her student’s palm and with the other hand, touch familiar objects—a flower, a kitten, water. Water, always water… Helen settled down and accepted her new circumstances somewhat. She was astute and could precisely mimic the words Annie spelled—but clearly, she made no connection. Try as she would, Annie, who also had a short temper, became exasperated. On April 5, 1887, she again spelled w-a-t-e-r into her young pupil’s hand but this time, she dragged Helen to the pump house and held the struggling child’s hand under the stream of water until both were thoroughly drenched. Over and over again, w-a-t-e-r , Annie spelled in Helen’s palm and continued pump and splash her with water. Exhausted and dripping wet, Annie finally gave up and sat on the ground. Then, as if a lightbulb suddenly had gone off in Helen’s head, Helen frantically felt for the handle of the pump, grabbed Annie’s hand and put it in the stream of water, and in her palm spelled w-a-t-e-r. And in that moment, Helen Keller’s world unfolded around her. In her autobiography, Helen wrote:

“As the cool stream gushed over one hand, Teacher spelled into the other the word “water,” first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten–-a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that ‘w-a-t-e-r’ meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away.”

Sullivan herself described the event in a letter to the matron of the Perkins School: “The word coming so close upon the sensation of cold water rushing over her hand seemed to startle her. She dropped the mug and stood as one transfixed. A new light came into her face.”

This was the defining moment in Helen’s life. Like Annie, her thirst to learn was insatiable. She would feel for an object and Annie would grab her hand and spell the word into Helen’s palm. Within six months, the exceedingly bright child who had been so starved to communicate had learned 575 words, multiplication, and the Braille system. “Teacher,” as she called Annie, and Helen were inseparable the next 50 years.

In 1888, with Captain and Mrs. Keller’s blessing, Annie brought Helen to the Perkins School and remained with her as her private tutor and governess. In 1890, Annie accompanied Helen to Radcliffe College for Women, from which Helen would graduate with honors. She became a prolific writer and public speaker, and as her story spread and her fame grew, she took on causes, campaigning for the rights of the disabled, supporting the women’s suffrage movement, and assuming strong and often controversial political and social positions. She met numerous personages, such as Charlie Chaplain and Mark Twain, 13 U.S. presidents, from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon Johnson, and traveled the world—with Annie, as ever, by her side.

On May 3, 1905, Annie married Harvard professor and literary critic John Albert Macy. The marriage was short-lived, and they separated but remained legally married until Macy’s death in 1932. Annie never remarried.

🙦

ANNIE’S EYES CONTINUED TO DETERIORATE as the years progressed and by 1935 she was completely blind. On October 15, 1936, she suffered a coronary thrombosis and lapsed into a coma. Helen never left Annie’s bedside and was holding her hand when, five days later, on October 20 Annie Sullivan Macy went to meet her Lord. She was seventy years old.

Annie’s ashes are interred in a memorial at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., the first teacher so honored. Helen died in 1968. Her ashes were interred alongside those of her beloved “Teacher”—the extraordinary woman known to the world, and across the years, as the “Miracle Worker.”