In 1958, distinguished American broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow interviewed Maria Callas at her opulent suite at New York’s famous Waldorf-Astoria. “Much has been said and written about your temperament. What do you have to say? Are you really temperamental?” he asked the world’s most celebrated diva. “What do you mean by my temperament, Mr. Murrow?” she replied, surprised. “I don’t understand that…” “I suppose,” he replied, “tantrums, throwing things…” “Oh, dear,” she demurred. “I have never, at anyone, though sometimes you feel like it! No tantrums. It’s not true. It’s just, disturbing situations that turn up, you know anything about it, you just react as any normal human being.” The fact is, Maria Callas was not just any normal human being. That same year, 1958, she walked out of the Rome Opera, was barred from appearing at La Scala in Milan, left her husband for Greek tycoon and shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, and was fired from New York’s Metropolitan Opera by its legendary director, Rudolph Bing.

Surrounded by fans and draped in a glamorous tulle gown, Callas reaches out to grasp a supporter’s hand from onstage, circa 1965. As her fame erupted, Callas quickly became an icon in the opera world. Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy.

When interviewed he stated, “There came to a point where I had to decide was Madame Callas running the Met or was I running the Met, and at that time, I was running the Met—and said so—and cancelled her agreement.” The unprecedented incident caused an explosion heard far outside the opera community and in a world where few did not know the great Callas—so great, she was known as “La Divina.” Again, Maria Callas appeared on television with Murrow at the height of the fracas. The respected English conductor, Sir Thomas Beecham, was streamed in live, on television, from London. “Can I ask Madame Callas a most important question?” he asked. “One of the most startling rumors is that Madam Callas is supposed to have hit [a director] over the head with a bottle of brandy, and I want to know if that is true or not.”

Taken aback but nonetheless quietly grinning at the humor masked behind the question, Maria replied: “The newspapers have written so much, and so much, that God only knows. I would’ve by where readers would have believed half of the half because I don’t believe anything because when I read it, I have the shocks of my life,” the New York native replied in the quasi-accent, broken English she had acquired in her 25 years living as a European. “Could it have been a bottle of something else, madame?” Sir Thomas then asked, earnestly. Feigning indignation Maria replied, “I never threw anything at anyone, unfortunately, and if I did, it would be a shame for the bottle, you know!” Maria Callas, the diva, the greatest name in opera, lived a life constructed on drama as rich—and ultimately, as tragic—as any of the opera roles she had sung on stage. Born Maria Anna Cecilia Sofia Kalogeropoulos on Dec. 2, 1923, in New York City to Greek immigrant parents, she was 7 years old when her mother left her father and returned to Greece with Maria and Maria’s older sister, Yacinth.

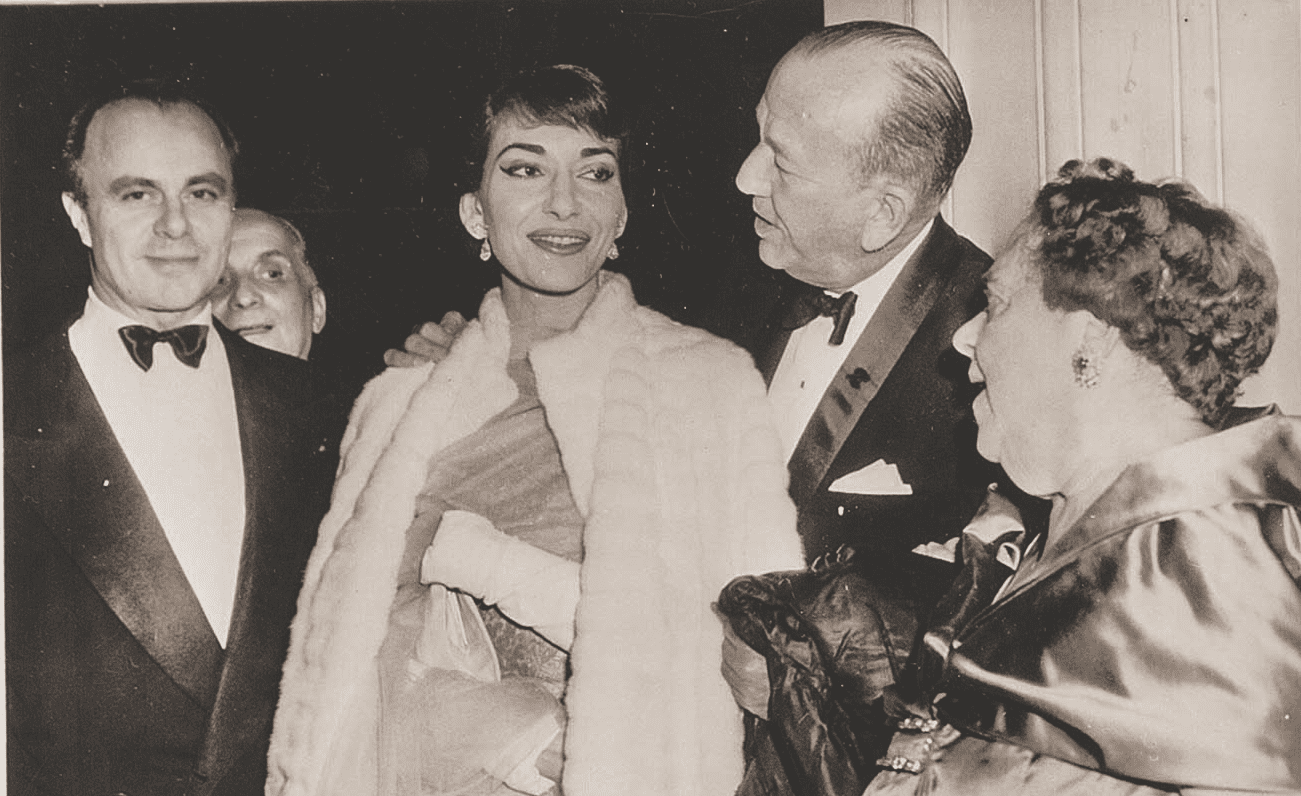

Callas smiles as playwright Noel Coward and famed party-giver Elsa Maxwell greet her at “Cuba Gala Night,” a benefit dinner dance intended to promote scholarships for Cuban fashion designers studying in the U.S. The event was held at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria by Earl Smith, U.S. Ambassador to Cuba. Photograph courtesy of Heritage Auctions / HA.com.

Their mother, Litsa Kalogeropoulos, had lost her firstborn child, a son, and was certain her third would be a boy. When a daughter was born instead, Litsa determined she would never show her any love, and she never did. In 1939, when Maria was 14 years old, she was accepted into the Conservatory to study music. Her overbearing, strong-willed mother lied about her daughter’s age, confident she would become the family breadwinner as a singer. The storm clouds of World War II had gathered, and soon the hardships of war set in. Maria’s mother forced her to sell herself to Nazi soldiers, so her family could buy food. Years later, as Callas rose to fame, her mother made extraordinary demands for money. Maria completely and forever distanced herself from mother and sister. “My mother used blackmail, unfortunately,” Maria reflected later in an interview. “They (her mother and sister) had a way of living that was not my way.”

The Making of Maria Callas

After the war, Maria Callas went to Italy to study with the great opera teacher Elvira De Hidalgo, who would be the closest thing Maria ever had to a mother. “She was the perfect student,” de Hidalgo said. “When she made a mistake while singing, I would tell her what was wrong. She’d answer, ‘Si, capito’—I understand—and never make the same mistake again.” Callas signed her first contract in 1942 at the Athens Opera House, where she sang Puccini’s Tosca, which became her hallmark role. She also sang Beethoven’s Fidelio and Wagner’s Parsifal. Callas then devoted her repertoire to the Bel Canto (“beautiful singing”) school of opera. Bel Canto not only suited Callas’ voice and performance style, but she dominated, and identified, that school of singing over any other opera singer to this day. Her career soared.

An enormous fresco of Callas on the side of a city building. IJL / Stockimo / Alamy.

She was taken under the wing of some of opera’s greatest conductors. Maestro Tullio Serafin worked with her to perfect the Bel Canto technique and repertoire. Serafin also taught her to forget about the notes she was singing and focus on the truth of interpretation. This would define her as a singer. When Maria Callas was under the guidance, and spell, of Luchino Visconti (“she was like a schoolgirl with a terrible crush,” one friend observed), Callas commented, “I was thoroughly spoiled by him because he was the Grand Seigneur treating the Prima Donna lavishly—and I enjoyed it thoroughly. He taught me the less I move without evident reason, the more it is my own personality.”

Subsequently, when she performed La Traviata, conducted by Carlo Maria Giuliani, at La Scala, she found a kindred spirit. Their approach to the relationship of the music with the drama on stage created such a chemistry that after four performances of La Traviata, 17 more were scheduled the following season. One of Callas’ most important professional relationships and friendships was with the great Italian director Franco Zeffirelli. He was one of the great influences on Callas’ life. When asked to describe her as a performer, Zeffirelli said, “If I had to pick one thing, it would be pathos. She could bring to the turmoil of Tosca a pathos.”

Maria Callas, 1950. Marka / Alamy.

Callas, the Prima Donna

After a performance, Maria, then 26, met Giovanni Battista Meneghini, an Italian industrialist 27 years her senior. Less than a year later, in 1949, they married—she for the life and security of his money and he for the glamorous life of the opera. But he also realized she was lonely and adrift personally, and he became fascinated by her. There was no romance, however. She sang under the name of Maria Meneghini Callas, and he would control her life and career until 1959, when Aristotle Onassis entered her life. In 1949, immediately after her wedding, Maria, the new bride, left for Argentina without her husband to perform Turandot, by Puccini, Verdi’s Aida, and Bellini’s Norma. From 1948 to 1952, she gave over 173 performances of 18 operas. From Mexico, she went to Naples, Buenos Aires, London, Venice, Sao Paulo and Rome, where she was acclaimed as the greatest Prima Donna of all. Yet Milan’s Teatro alla Scala, the temple of opera, still refused to make Maria its Prima Donna. As she perfected her voice and acting, the only challenge that remained to her was her body.

Being a perfectionist, she felt her interpretation of her Bel Canto heroines had to be as credible as possible—especially her Violetta in La Traviata, a young woman dying from consumption. Callas envisioned her as slim, almost skinny. Above all, Maria wanted to change her appearance and be recognized not only as a great singer but also as a glamorous woman. In 1953, she lost 80 pounds in 10 months and became one of the most glamorous women in the world, wearing extraordinary gowns, coiffeurs and jewels. She was unlike any diva the world had ever seen. In 1951, La Scala’s director, Antonio Ghiringhelli, finally surrendered to the public’s adoration of Maria, and she opened the season with I Vespri Siciliano. It was an absolute triumph, and Callas was reborn as “La Callas.” The same season at La Scala she sang Violetta in Verdi’s La Traviata and Bellini’s Norma, the two operas Callas would perform the most in her career. In striking ways, the theme in Tosca, a diva living and dying for love and her art, mirrored Callas’s life.

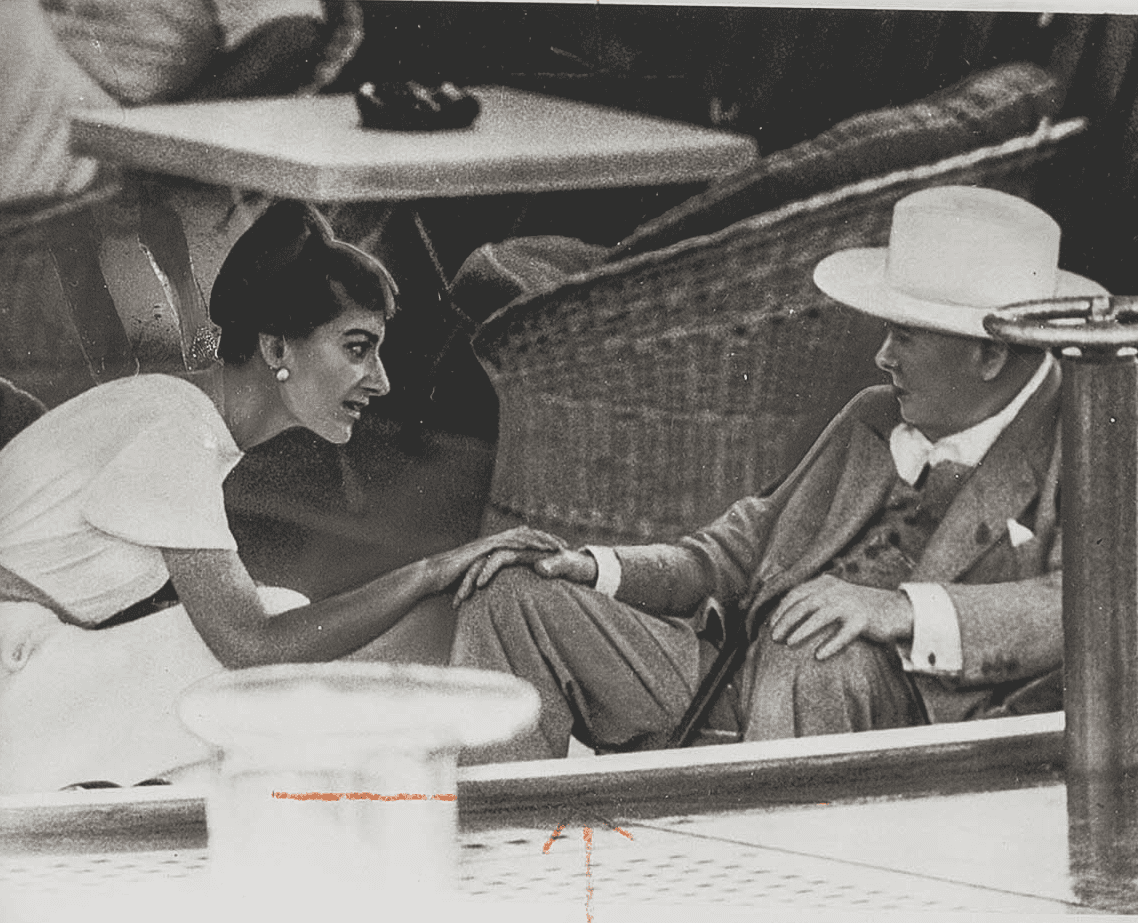

Callas chats with Winston Churchill aboard the yacht Christina after arriving in Monaco from a three-week Mediterranean cruise. On the voyage, Callas and Churchill were both guests of Aristotle Onassis. Photograph courtesy of Heritage Auctions / HA.com.

Tosca is a grand, intimate story adapted by Italian composer Giacomo Puccini from French playwright Victorien Sardou’s 1887 dramatic play of torture, murder and suicide, set in Rome in June 1800 as Napoleon Bonaparte is about to invade the Kingdom of Naples. Sardou, who wrote 70 plays, collaborated on several historical melodramas with the great French stage actress Sarah Bernhardt. La Tosca premiered in Paris on November 24, 1887, with Bernhardt as Tosca. Puccini’s opera Tosca premiered on January 14, 1900, in Rome. Callas sought to make the role her own. At the first rehearsal, she cleared the table of all music and papers and said she wanted to create the role from scratch. She brought to the role a femininity, beauty and freshness that had never been performed before.

Some critics claim her weight loss negatively affected her voice, but, in fact, it was more magnificent than ever. Maria Callas expanded her Bel Canto repertoire to include Cherubini’s Medea, Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, and Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma. In1955, her finest year, she returned to La Scala to perform La Vestale by Spontini, La Sonnambula by Bellini, and again, La Traviata, reuniting with Luchino Visconti. She was so spectacular that she was crowned Prima Donna Assoluta by La Scala—the absolute Prima Donna. American soprano Leontyne Price and English soprano Joan Sutherland were among the few to earn such a distinction. It was 1956 when Callas made her Metropolitan Opera debut in New York, performing Norma, Tosca and Lucia di Lammermoor.

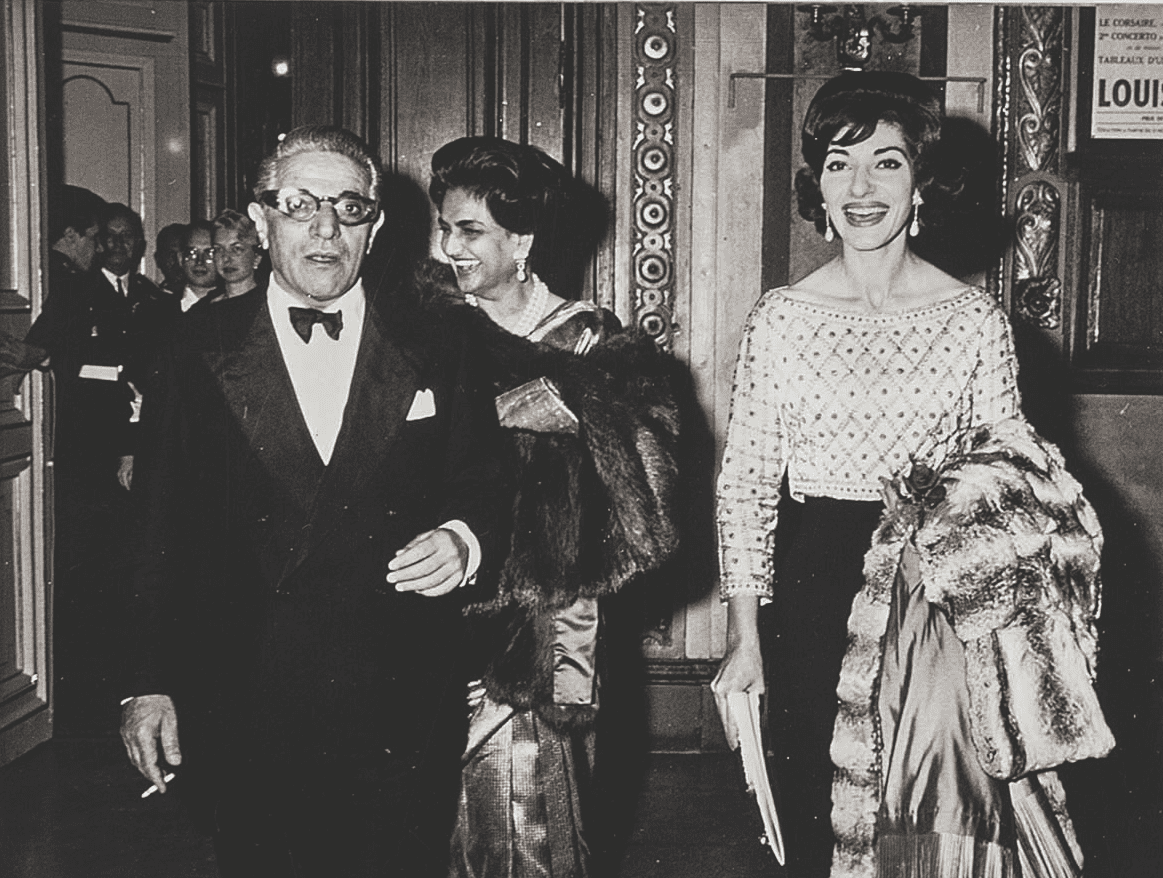

Greek shipowner Aristotle Socrates Onassis and Callas, followed by the Maharanee of Baroda, leave the Opera of Monte Carlo after attending the ballet “The Queen of Spades.” Photograph courtesy of Heritage Auctions / HA.com.

Onassis

In April 1956, Callas met Aristotle Onassis in Venice at a party given in her honor. Callas was performing Anna Bolena at La Scala. The critics called her interpretation “an unreal and superhuman performance,” and the opera world christened Callas La Divina “La donna la voce La Divina.” In 1958, Callas performed at the Opera Garnier in Paris for the first time. This was a particularly difficult time in her career. A huge scandal in Rome had just ensued when she became sick after the first act of Tosca and left a glittering audience of dignitaries, celebrities, heads of state and movie stars angry and disappointed. The incident and the defamation she suffered plagued her the rest of her life. In 1959, Maria Callas and Meneghini were invited on a summer-long Mediterranean ruise on the world’s grandest yacht, Christina, by its owner, Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis and his wife, Tina.

There was an instant dynamic between the two Greeks, Callas and Onassis, and in the course of the cruise, the two began their affair that would, in the end, destroy them both. For the first time in her life, Callas experienced a passionate sex life. “She did not have sex, perhaps once a year with her husband,” one friend commented. Onassis had an enormous impact on the emotional and physical life of a woman who had experienced years of no emotion, no sex, from a husband who increasingly was seen as an obstacle rather than asset in both her professional and private lives. Though Meneghini had showered Callas with his wealth and successfully managed her career, he was no longer of any use to her. When the yacht finally docked, the two left their spouses behind and went off together.

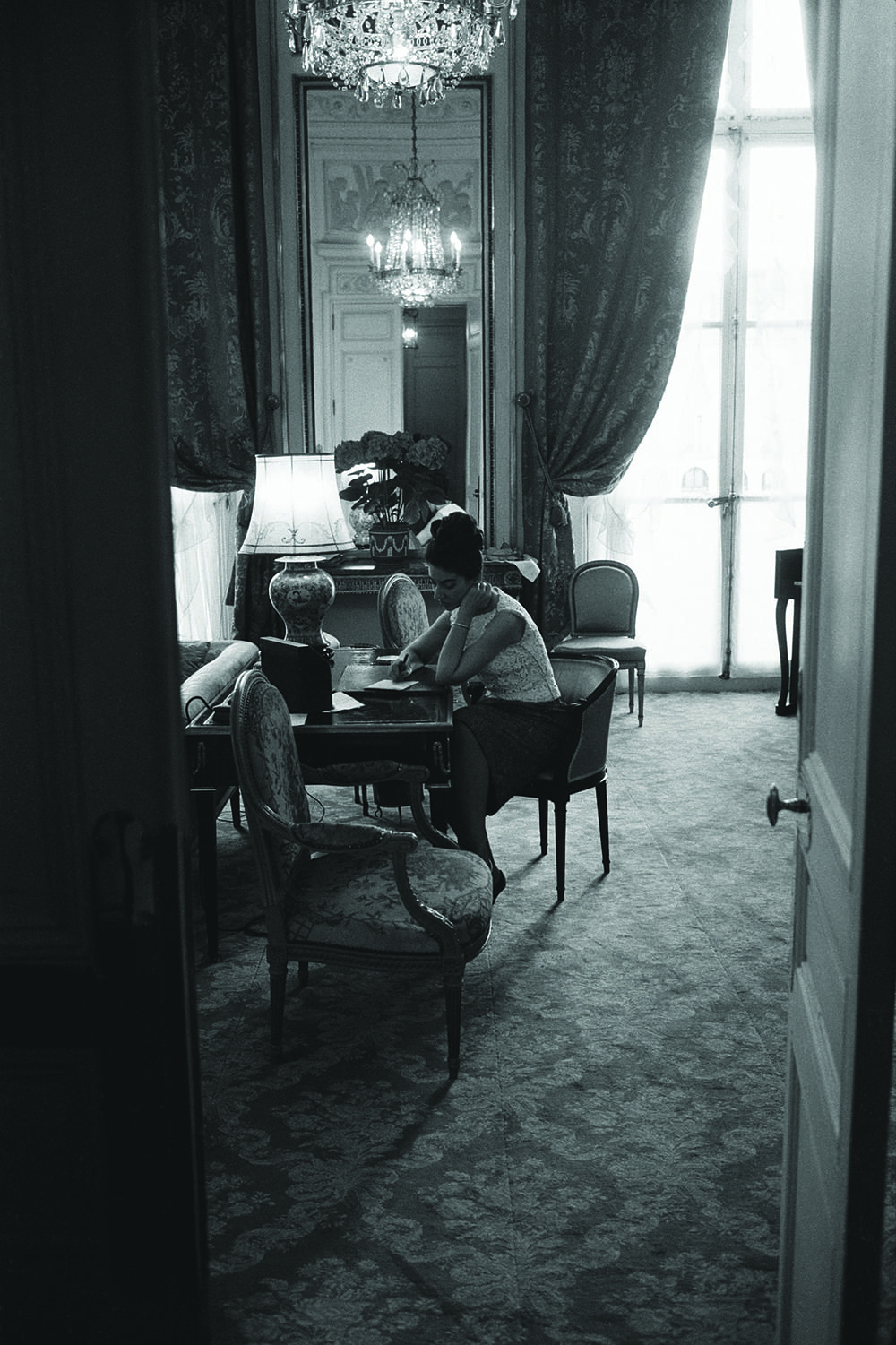

In preparation for her recital in honor of the Order of the Knights of Malta at the Champs-Elysées theater, Callas sits in her hotel room taking notes at her desk while the city of Paris peaks through her window. Photograph by Jack Garofalo / Paris Match via Getty Images.

Onassis started divorce proceedings against Tina, and Callas, claiming her husband had mismanaged her career, started proceedings against him. Reams have been written on the explosive, ill-fated relationship between Callas and Onassis. Maria Callas had found the love of her life in Onassis, but those who observed them from their social circle believed he never reciprocated with the same intensity. For eight years, her life was absorbed into his; she abandoned her career. All her life Callas wanted a family, and she would have happily forfeited her career and fortune to have children. She tried to get pregnant with Meneghini but could not conceive. With Onassis, she did. On March 30, 1960, Maria, age 37, delivered a baby boy. He lived that one day. A picture was taken of the innocent, which Maria kept—and had with her when she died.

The Attempted Comeback

Throughout her eight years with Onassis, Callas maintained she needed to detach from her career, living not as the great “La Callas” the soprano, but as Maria, the woman. “Years go by very quickly,” she said in an interview reflecting on those years away from the stage. “I wish I was what I was 20 years ago. The acrobats and top notes, they used to be, and you know, the fireworks that a young person has.” Nonetheless, she attempted a comeback. When she opened her tour in Hamburg, she received acclaim for the actress, the personality—but not the voice. “I don’t really read the critics,” she commented when told of the negative reviews. “During my full glory I have always had bad critics. The fact that I have made a career without public relations or bribe newspapers or build my image has made things difficult. To have a job you have to be nice to some person or another. Very few persons reach the peak with no help at all but your own talent.” Many people believed her career had peaked; some said it was over.

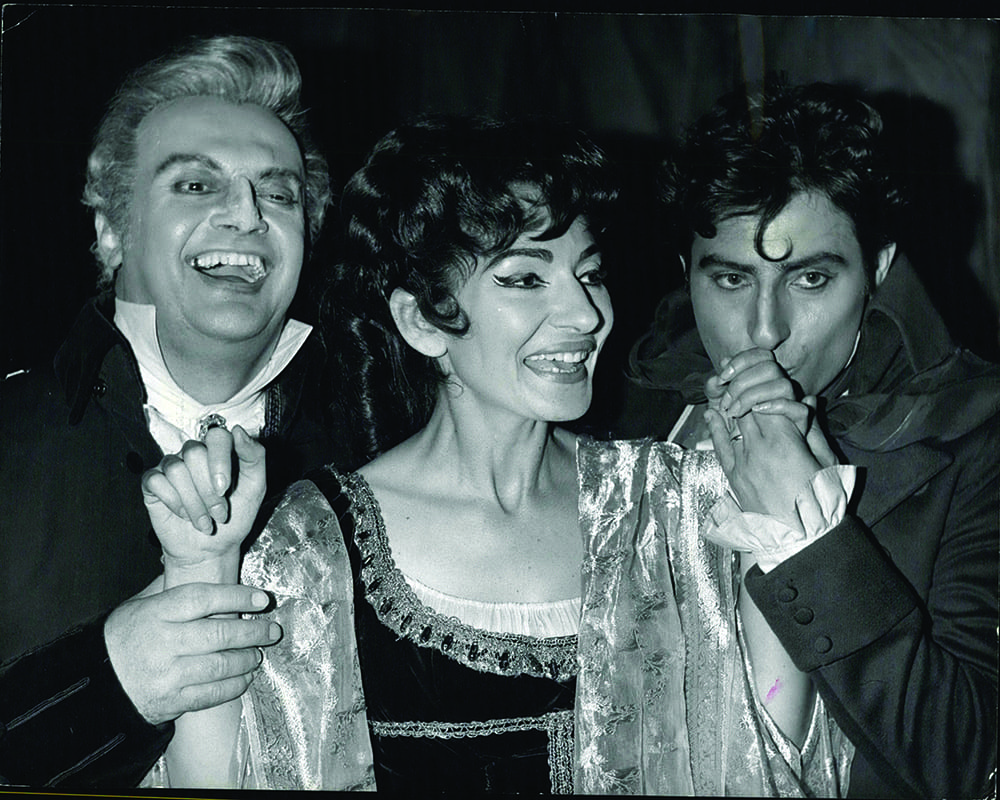

Always the center of attention, Callas is joined at Covent Garden by her two co-stars Tito Gobbi (left) and Renato Cioni (right) to take a curtaincall after her comeback performance in 1965. Photograph courtesy of Keystone Press / Alamy.

Contrary to the general belief that Onassis maintained a stranglehold on Maria, he actually urged her to perform, to train. But she began to smoke, went to bed late, was not practicing, and was so involved with her relationship with Onassis that she told him she didn’t want to sing anymore. It was then that the greatly respected administrator of Covent Garden, London, Sir David Webster, ganged up with Franco Zeffirelli for a new production of Tosca at the Royal Opera House as a ploy to get Callas on the stage. She could not ignore that bait and agreed when she was told that playing opposite her was her friend, the great Italian baritone Tito Gobi. On opening night, January 21, 1964, Callas, consumed with fear, was physically prevented by her dresser from leaving the theater. Zeffirelli and the stage director had to physically push her on stage for her entrance. On stage again after so many years, La Callas came alive and gave the performance of her life.

Zeffirelli could not have done more to support Callas’ return than pairing her with Gobi. Not only was he her friend, but they were simpatico, equals; he played off her, and equally she played off him. Maria Callas and Gobi would shift slightly every night they performed, creating a fresh moment as they interacted. Ultimately, they set the bar so high that no one has yet come close. Maria’s ability to define and refine Bel Canto phrasing was one of her greatest powers. She was determined her characters would not be one-dimensional. Great sopranos become the part they play, but Callas embodied the women she played as if by birth—Tosca, Violetta, Aida, Carmen, Medea, Manon, Elvira in Bellini’s I Puritani and Maddalena in Andrea Chenier. Tito Gobi understood this. In Tosca, he observed, Callas would “go to the absolute limit.” She kills Gobi’s Scarpia because she is afraid of becoming his victim. Both Gobi and Zeffirelli confided they saw Onassis in Scarpia. After her comeback, the question arose: Did Maria really want to escape café society after all? Clearly, she wanted to become Mrs. Onassis.

Callas takes an excursion in the fishing village of Portofino in Italy as she and a group of friends travel on Aristotle Onassis’ yacht. The group is comprised of Onassis’ first wife, Tina, daughter of Winston Churchill and actress, Sarah Churchill, and Umberto Agnelli’s wife, Antonella Agnelli. July 27, 1959. Photograph courtesy of Keystone Press / Alamy.

But did she genuinely want to abandon her career? On May 22, 1964, Callas walked onto the stage of the Paris Opera to perform Norma. In the last act, as she hit the last high note—considered the most spectacular note in opera, the high E-flat—for the first and only time in her career, she couldn’t sustain it. On March 19, 1965, she gave two performances in New York to herald her historic return to the Metropolitan Opera. She was met at John F. Kennedy International Airport by cheering crowds and hordes of press. At the Metropolitan Opera house, the line for standing-room-only tickets formed four days before the performance. The first performance was historic for another reason. Jackie Kennedy was in the house. There was a standing ovation when the young widow of John F. Kennedy entered the hall to take her seat. Then things quieted down… and there was the voice of Maria. At the first note, the audience again rose to their feet in a furious, wild, five-minute ovation before settling down for the performance. The applause for Jackie was polite, respectful and restrained. The applause for Maria was deafening, boundless, almost out of control.

Finale of La Divina

Over the next two months, Maria Callas performed a run of Normas—then fate struck. She collapsed as the curtain came down on the opera—and her career. Callas’ blood pressure was dangerously low. The turmoil in her life with Onassis, his affairs, her fear of losing him, the anxiety and exhaustion from performing, had taken its toll. Directly after this trauma at the Paris Opera, Callas was scheduled for four more performances at Covent Garden. She cancelled three and kept only one—the Royal Gala Performance, to be attended by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth and Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. “I can give one performance,” Callas announced. The British were unforgiving. When the curtain rose on the first act, there was a horrible silence. However, Callas’ witchcraft started to work.

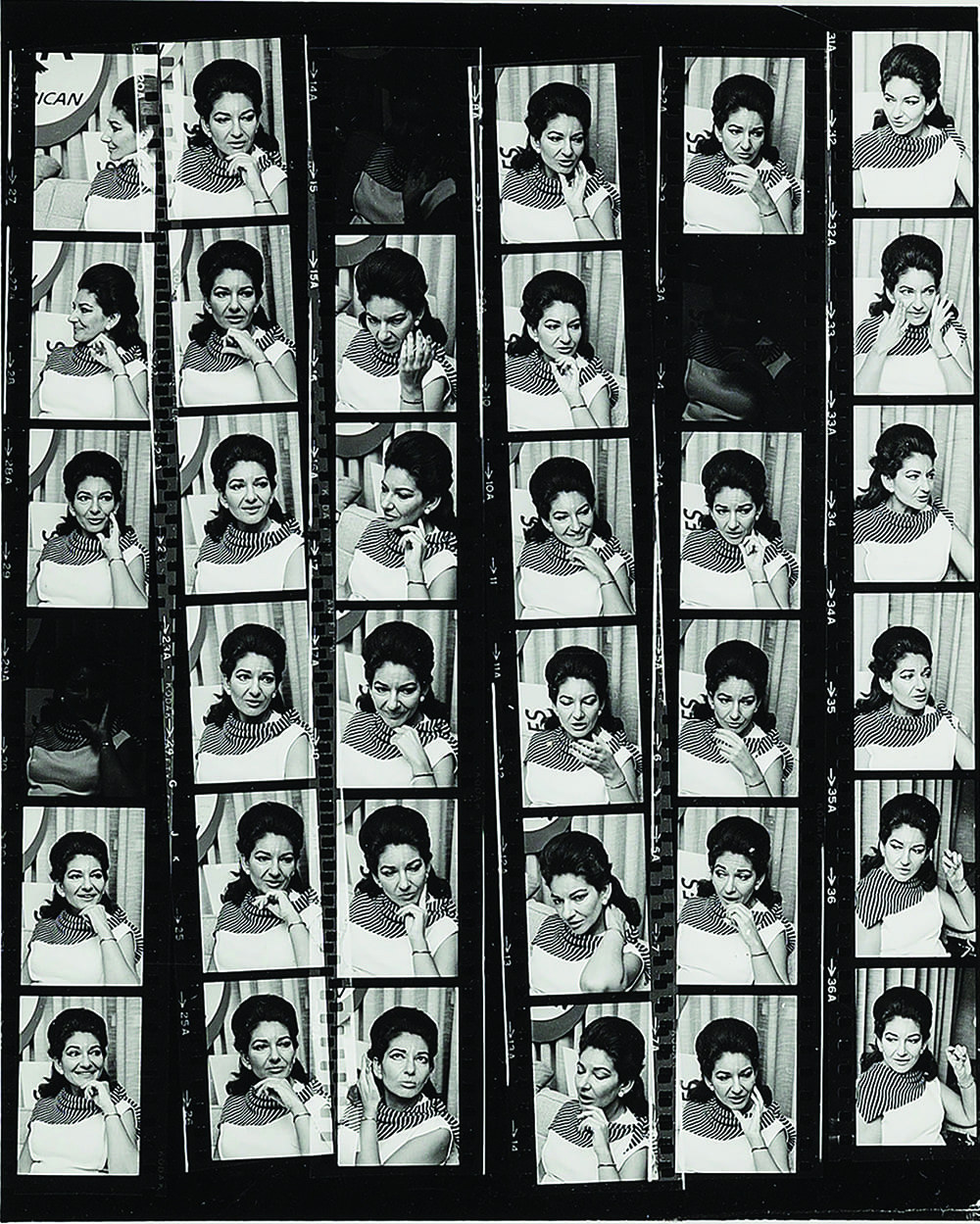

The diva’s range of emotion are captured throughout an interview. Callas became well-known for her temperament and was even nicknamed “the Tigress.” Photograph courtesy of Heritage Auctions / HA.com and the Ava Gardner Estate.

The audience warmed up after the second act. By the end of the opera, she owned the audience. Nonetheless, the horrible experiences of her career deeply hurt her. She lost confidence. It was the beginning of the end. The final note she sang as Norma at Covent Garden was the last note she would sing on the opera stage. As she prepared to leave her dressing room, she told a friend, “Callas is dead.” Old nightmares plagued her — her tormented relationship with a mother who never loved her, her failed marriage, and now, the loss of the only man she ever loved. Rather than leave opera totally, she taught at the famed Julliard School of Music in New York. She proved to be a great teacher, and from 1971 to 1972, Callas shared the wisdom and secrets of the most extraordinary career opera had ever known. She loved teaching, but everyone asked when The Divine One would sing again. She never answered the question. The voice remained silent.

Life Imitates Opera

Maria Callas was naïve to believe that Onassis would ever marry her. He began seeing Jackie Kennedy in 1965, making “friendly” visits to the United States. Perceived as a romantic relationship by the press, it was based on money, fame and notoriety. Maria went berserk. She took pills and was hospitalized. There were big scenes on the phone. Onassis wanted both women but felt he had to marry Jackie because conducting an affair with the former First Lady would have created a scandal—and besides, Jackie was encouraging him. A lavish spender whose finances were not unlimited, Jackie saw marrying Onassis as a business contract that could ensure her lifestyle, and on October 20, 1968, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy became Mrs. Aristotle Onassis. Though the marriage ended in divorce in March 1975, during their six years together the couple seldom spent time together and rarely on the same continent at the same time. Maria learned of the marriage in the newspapers—Onassis never had the decency to tell her. On his wedding night, he phoned Maria multiple times, penitent. She would not take his calls. Never once was she nasty about Jackie.

Callas is illuminated by the spotlight as she performs the role of Violette in the opera La Traviata alongside Ettore Bastianini. Photograph by Giuseppe Verdi, circa 1955. Photograph courtesy of Interfoto / Alamy.

When asked, Maria Callas said she didn’t know her, couldn’t blame her. She kept a poker face with the press: “Mr. Onassis and I—we had a wonderful life,” she said when interviewed. “I don’t regret any bit of it. I regret when I stopped singing. I worked less and less. He did not want to see me sing.” And, “In some ways, both of us are probably in love. Both of us understand each other as nobody else. At a certain stage, love becomes different. You see, if I was brought to the state that I left him, it meant that at the deep core I didn’t love him. There are not many men who would marry me. It’s a sort of a handicap to be famous.” None of this was true. In private, Maria was devastated, furious. “He deceived me,” she confided to friends. Just 10 days after his wedding to Jackie, Onassis flew to Paris, to Maria, who he now understood was the love of his life. The longer he was away from her, the more he regretted marrying Jackie. The marriage quickly deteriorated as Onassis’ urgency to go back to Maria consumed him. He hired lawyers and told them to find a reason for divorce. He could have filed for adultery, perhaps, had Maria taken him back, but she had built a wall after the cruel trick he played on her.

The real-life saga played out like a Greek tragedy. Onassis’ beloved only son, Alexander, died in a small plane crash on January 23, 1973. Seeking the consolation only Maria could give him, Onassis flew to Paris to seek comfort from her. “He’s gone, my son is gone,” he told Maria. Onassis was completely crushed. The once powerful, vibrant, electric man never recovered. Then, on October 10, 1974, Onassis’ first wife, Tina, committed suicide. On March 15, 1975, Aristotle Onassis died at the American Hospital of Paris at age 69 from respiratory failure, a complication of myasthenia gravis, which he suffered in the last years of his life. The divorce proceedings with Jackie had been hostile; nonetheless, as a public show, Jackie visited her estranged husband before leaving for New Hampshire on a ski holiday. She ordered nurses not to admit Maria should she turn up to visit Onassis. With the end looming, Onassis’ sister, Artemis, phoned Maria and begged her come quickly if she was to say goodbye to her great love.

The captivating Callas gazes on as she is photographed at Covent Garden in London, England. Covent Garden is home to the Royal Opera House where she would eventually carry out the performance of her lifetime. Photograph courtesy of PA Images / Alamy.

Maria by that time had become a recluse and had not left her apartment for months. Upon receiving the call, however, she left immediately and snuck in through the service entrance of the hospital and up the back elevator. Onassis was barely conscious. “It is me, Maria—your canary,” she whispered to him, and told him she loved him and always would. Maria’s life was very dark and unpleasant after Onassis died. She stayed home, went for walks and to restaurants alone wearing big sunglasses and scarves, and listened to her recordings over and over. Almost all her friends had abandoned her, and she grieved over what might have been. “How slow death comes to those who long for it,” she sang as Tosca. On September 16, 1977, 21 months after Onassis’ death, Maria Callas died in her apartment in Paris, at age 53, from, it was said, a heart attack. Those who knew her, who loved her, know better. Maria Callas died of a broken heart.

The Curtain Falls on the Final Act

The legacy of La Divina, La Callas, The Tiger, has inspired generations. She opened the door to the popularity of opera at a time when interest was waning. What remains—her recordings, interviews, and photographs—show a woman who touched people’s souls in a curious way. The movie version of Medea in 1974, one of the few times Maria was filmed, was not a success, and yet, in her screen performance, it was clear how she drew people to her. In 1961, when Maria Callas was losing her voice, she performed Medea at La Scala and was booed by the audience. During the aria, “Dei Tuoi Figli,” she raised her fist toward the audience and shouted, “Ho dato tutto a te!”—I gave everything to you! By the end of the aria, not only had the boos ceased, but the audience was on their feet shouting cries of adoration. Ho dato tutto a te. Maria Callas indeed gave everything to us.

Written by Laurie Bogart Wiles

Author’s Note: Every quotation is verbatim from recorded, televised, or written interviews by Miss Callas or about Miss Callas by others.