By Jean Li Spencer

“If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” So said Shirley Chisholm, the famed women’s rights activist, who wore blazing white in honor of the suffragists on the day she became the first black women elected to Congress in 1968. It’s a bit of advice that still holds much weight today, when the right to vote is at stake as we decide how Constitutional voting will take place in the age of COVID-19.

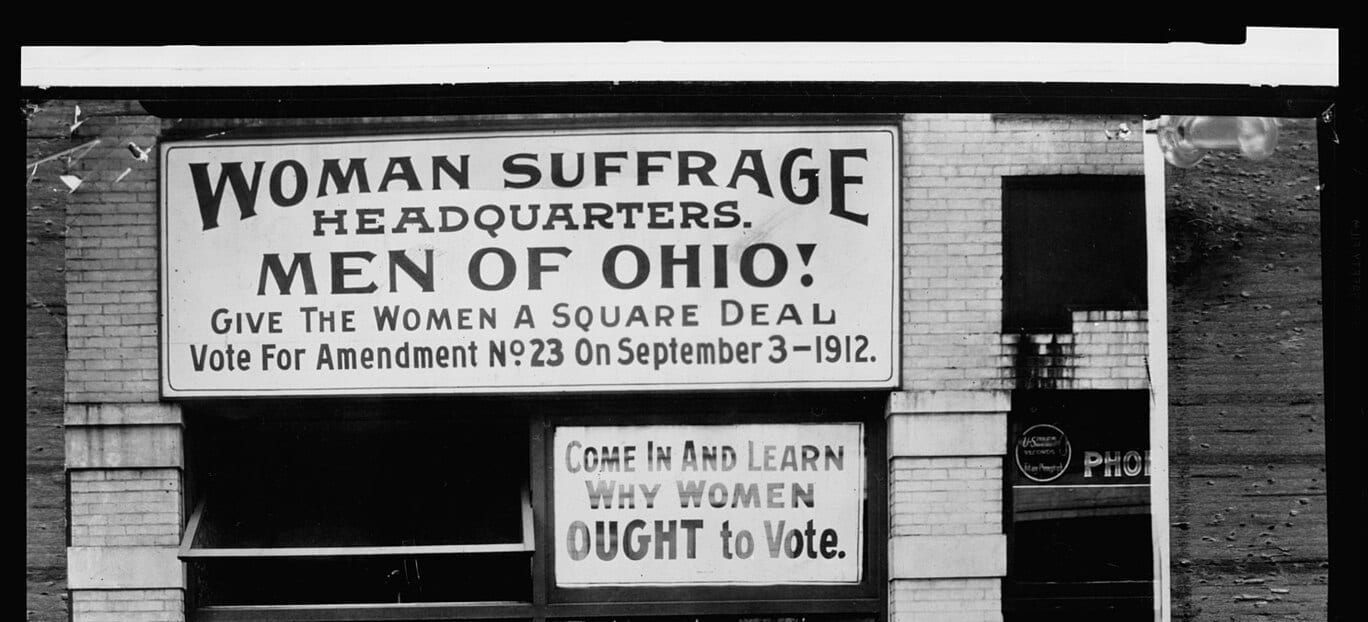

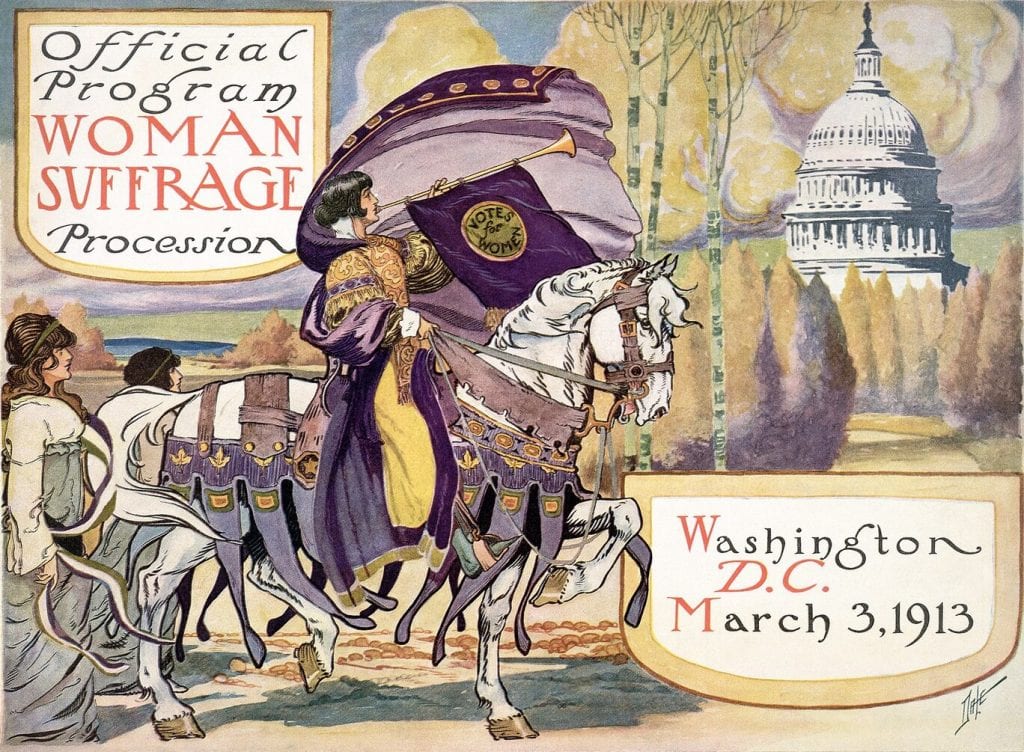

Ratified on August 18th, 1920, the 19th Amendment granted American women the right to vote. A terrific milestone in a much larger endeavor to employ women in public life, the 19th Amendment was one of the first steps in women’s liberation that would equalize the opportunities promised in the Declaration of Independence to both sexes– early white feminists actually drafted their own Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention, but the original manuscript is, sadly, lost. This declaration wrote women explicitly into the nation’s interests: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.”

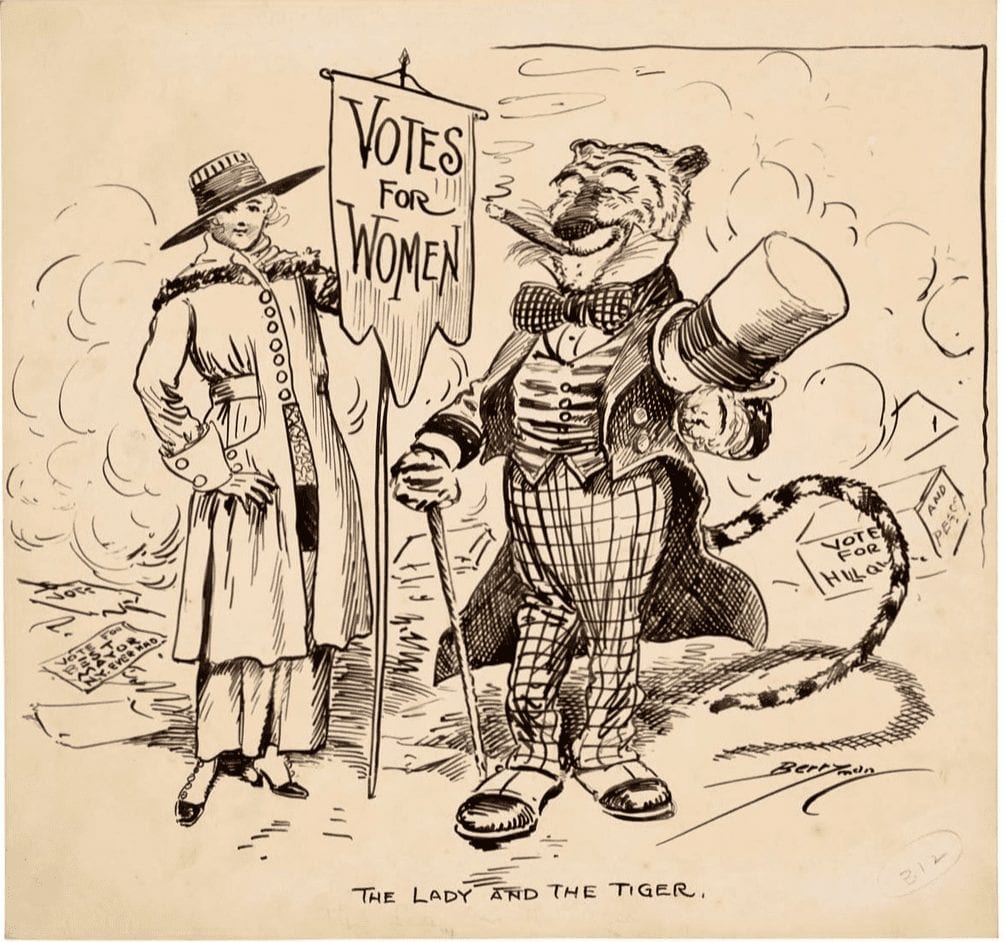

The suffrage movement of the nineteenth century converged interests that were inclusive towards women of color, such as the Antislavery Convention of American Women of 1837, which was attended by white, Black, and Native women. But the need for inclusiveness led to an irrevocable split between two dominant groups within early suffrage; a schism in opinion that fractured the fight advantageously towards white women over other oppressed groups, including Black men. (Perhaps if the 15th Amendment, which would have given African American men the right to vote in advance of women, had gotten greater push from white suffrage leaders, it might have been ratified earlier than the 19th Amendment.) The suffrage movement was born from a desire to grant all women the right to vote, and yet it took many more years after the 19th Amendment was passed to fully attain the truth of that law. White women were granted the ballot in 1920, but Asian American women had to wait until 1946 until their vote was granted, while Native American women were prohibited until 1962, Black women until 1965, and Latino American women until 1975.

Society tends to teach the history of the suffrage movement as though it were a monolithic phenomenon, when in reality it took not a village, but a cacophony of voices across the nation, to turn suffrage into a revolution: African-American women like Juno Frankie Pierce and Ida B. Wells-Barnett; Native American women such as Zitkala-Sa and Debra Lekanoff; Latina and Asian women like Jovita Idár and Patsy Mink– these trailblazing women led thousands of Americans to campaign for equal rights and still remain largely unrecognized.

While women have had the right to vote for a solid century now, let’s not forget that it took many resilient women (and their male allies) almost that long to get the law passed. These days, the term “suffrage” seems antiquated, if not entirely archaic, like the petticoats worn by the first feminists. Our general idea of what it means to be “woman” has grown into itself in many necessary ways– such as the recognition of transgender women as “women”– but it has also collapsed into alarming, regressive definitions that harm us as a whole. Women’s rights have invariably been a political issue, yes, but in this fraught environment where even identifying as a woman feels like a political statement, perhaps the most pressing reminder that is needed in the world is the reminder that women’s lives and bodies are more than divisive political tools. Carrie Chapman Catt, founder of the League of Women Voters, voiced a very succinct defense for why the right to vote is important for women: “That vote has been costly. Prize it! The vote is a power, a weapon of offense and defense, a prayer. Understand what it means and what it can do for your country. Use it intelligently, conscientiously, prayerfully.”

In 1920, approximately 10 million women cast a ballot, with a turnout rate of 36% in comparison to 68% for white men. Since then women voter turnout rates have increased and exceeded male turnout rates since 1980, when 61.9% of women voted compared to 61.5% of men; and in 2016, the difference between women and men was a stark 4%– with women casting almost ten million more votes than men in recent elections– according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. That means that women are representing the heart, soul, and mind of the nation. It also means, that in an era when women continue to be undermined, it is important that we all exercise our right to vote.