After Auschwitz was written, directed, and produced in 2018 by Jon Kean in association with Bala Cynwyd Productions and the Holocaust Museum of Los Angeles. In this powerful, vivid documentary film, available for streaming, six female Jewish Holocaust survivors of Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau recount their suffering and losses. The six courageous women who triumphed over death are Eva Beckmann, Rena Drexler, Renee Firestone, Erika Jacoby, Lili Majzner, and Linda Sherman. Know their names. They lived to tell their story, and that of the 1.3 million who perished at Auschwitz, the largest death camp of Hitler’s “final solution to the Jewish question.” We know too well the stories of acute suffering human atrocities, but After Auschwitz captures “what it means to move from tragedy and trauma towards life.”

Several immersive experiences are also available. In April 2022, Rider University in New Jersey created a virtual reality experience called “Holocaust Studies Immersive Experience,” allowing those with an Oculus virtual reality headset to experience Anne Frank’s house. Even those without the VR equipment can watch short videos that also feel quite immersive. Visitors at the Illinois Holocaust Museum can slip on a virtual reality headset and experience the moment a terrified teenager stepped off a boxcar at Auschwitz in 1944 in “A Promise Kept.” Witness: Auschwitz, another intense VR experience, was created by Italian games development studio 101% to give an authentic “day in the life” in Auschwitz and, despite the new immersive technology some consider to be triggering, is officially supported by the Union of Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI).

The Shoah Foundation, housed at the University of Southern California tells and preserves the stories of Holocaust victims through multimedia, ongoing research, and education “to develop empathy, understanding, and respect through testimony.” The foundation houses 55,000 first-hand testimonies and was founded by Steven Spielberg in 1994. Most likely, that was not a film that I myself would have gone to see at the movie theater had my old friend, Otto Ninow, not telephoned.

“I haven’t been to a movie theater in 40 years, but I want you to take me to see a movie,” Otto said in his thick German accent. “It is called Schindler’s List.” I knew my friend’s story. “Are you certain, Otto?” I asked.

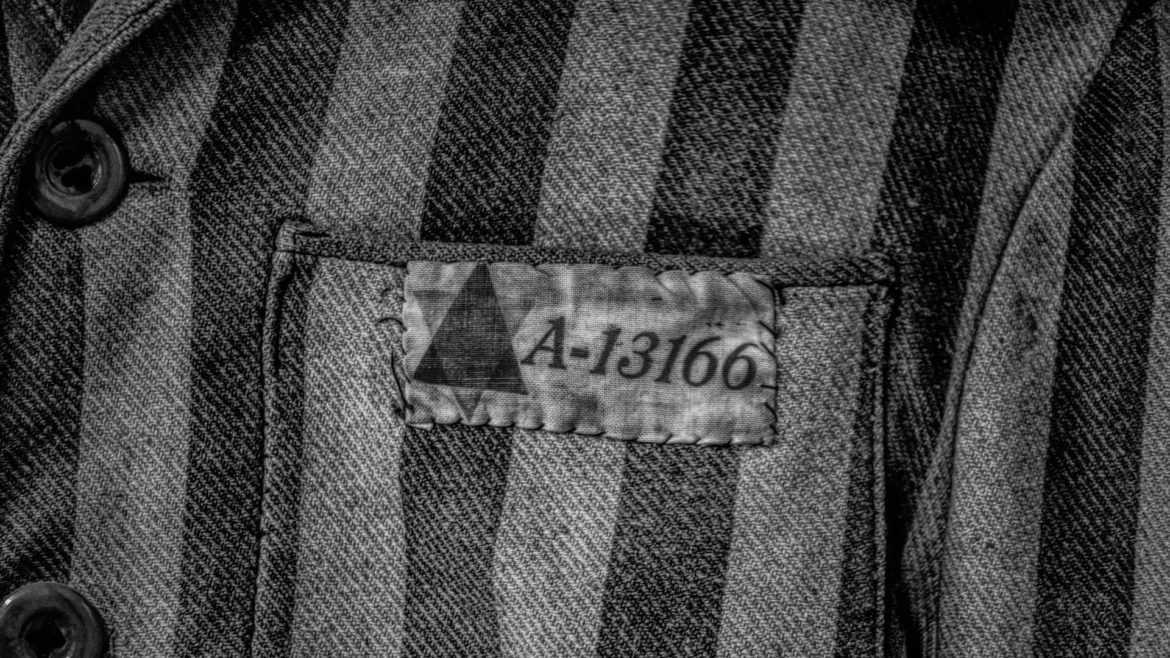

Born in 1910 in Bremen, Germany, Otto was 16 when he was conscripted into the Hitler Youth, before being interred at Dachau Concentration Camp as he was a mischling (half-Jew) in 1940. He escaped death by firing squad three times from Nazi camps, and after the last time, he walked barefoot and alone through the winter snow to return home to his mother in Dresden. When he arrived, he learned his mother was dead. Unable to carry the unbearable grief of losing all 21 members of her family to the death camps, and believing her only child, Otto, was dead too, she died by suicide the day before.

Miraculously though, Otto was eventually reunited with his young wife, Lisa, a German Jew who survived Auschwitz, and after the war, composer Irving Berlin heard Otto, a professional clarinetist before the war, at the American Club in Berlin and invited him to come to America. In their travels throughout America, he and Lisa discovered North Conway, New Hampshire, which reminded them of home. He taught music lessons, and he founded a music shop and the Mount Washington Band, among many other achievements.

When we watched Schindler’s List, the theater was packed. Otto sat between me and his nurse, Nancy, who had cared for Lisa until her death four years before. From time to time I looked at Otto; beads of perspiration ran down his gray face. As he held my hand so tightly sometimes it hurt, I could not flinch. When the movie ended, people left the theater, of course, but Otto did not move. He stared straight ahead. We were alone for some time when finally, in a choked voice said, “I lived this. This was my story.”

Otto died in 1996 at the age of 86, shortly after suffering a stroke. Thousands lined the streets of North Conway as the Mount Washington Band led the funeral procession in honor of the great man. The stroke he’d suffered took away those terrible memories, and he only spoke of his beloved Lisa, his German Shepard, Heidi, and happy times. I like to think that was God’s way of blessing Otto, as if to say, “Well done, good and noble son.”