A person or personified force who is the source of inspiration for a creative artist.

She encourages, inspires, engages, influences, or otherwise enthralls, captivates, and captures an artist on an intellectual, emotional, sensual, and almost always, sexual level, transcending her admirer onto a higher plane than he otherwise may ever have experienced. The word is derived from the Greek noun, mousa, which literally means “art” or “poetry” or “to excel in the arts” and to comprehend the power of a muse, we must hearken back to Greek mythology, for there you will find the “original inspiring women”—the Nine Muses, the nine lovely, alluring daughters of Mnemosyne and the great Zeus, each gifted with a unique artistic talent, conceived when their parents lay together in connubial bliss for nine consecutive nights. For this reason, a muse can be nothing more or less than a goddess to the artist she inspires.

Venus de Milo

Perhaps the earliest example of the muse in iconic art was created by Ancient Greek sculptor Alexandros of Antioch. His Venus (sometimes known as the Ancient Roman counterpart, Aphrodite de Milos), was sculpted from Parian marble sometime between 150 and 125 B.C., during the Hellenistic period. Who his model was we do not know but her perfection deems her a goddess, and even without her arms, she is stunningly, realistically exquisite—the perfect interpretation by Alexandros of pure beauty. She was lost for centuries until a peasant named Yorgos Kentrotas unearthed her in 1820, on the island of Milos, and she became the most iconic of muses.

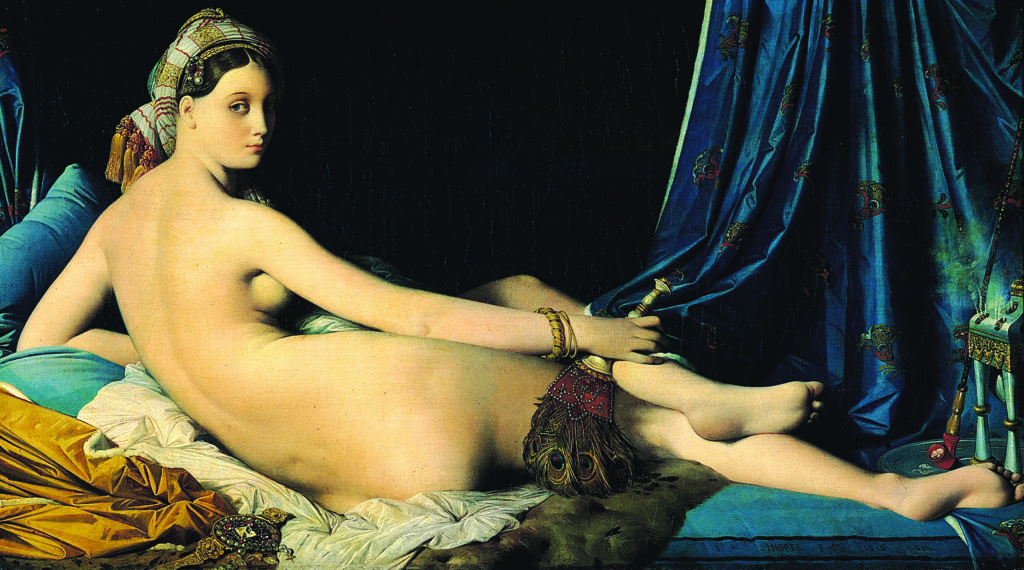

Grande Odalisque

One of the most noted muses in the history of art is the Grande Odalisque (concubine) by French artist J.A.D. Ingres. A great admirer of the 16th century Italian High Renaissance painters Raphael and Titian, and the Baroque classicist Nicholas Poussin, Ingres, in essence, exploits beauty. From an academic standpoint, his explicit nude reclining in an Orientalist setting was a giant leap by the artist from the Neoclassic style of the day to the burgeoning Romantic period. The thing is, such a woman could never exist.

Odalisque is a fantasy woman. Her pronounced curvature of the spine, distorted pelvis, five extra lumbar vertebra, and a significantly shorter left arm than her right does not indicate that Ingres, one of the greatest drafters in the history of art and a master of anatomy, was ignorant of the proper proportions of the female figure. It is quite the contrary. He purposefully painted the concubine suggestively lying on a divan for stylistic effect, her long, sinuous lines and skin bathed in diffused light is his depiction of a ‘reclining Venus,’ as is The Sleeping Venus (1518) by Giorgione, The Venus of Urbino (1538) by Titian, Madonna of the Long Neck (1535) by Parmigianino, and another reclining woman who looks over her shoulder at the viewer, Portrait of Madame Récamier (1800), by Ingres’s contemporary, Jacques-Louis David. But it is her gaze, her invitation to a sultan to take part in carnal pleasure with her, that conveys, through her alluring albeit distorted beauty, one of art’s greatest works.

The Birth of Venus

Early Italian Renaissance painter, Sandro Botticelli, was inspired by the 15-book continuous mythological narrative, Metamorphoses, by ancient Roman poet, Ovid (43 B.C. to 18 A.D.), to create his Neoplatonic-themed masterpiece, The Birth of Venus. The shy nude covers her private parts as a symbol of the birth of love and the driving force of beauty in spiritual life. Commissioned by the wealthy Florentine Medici family, the model is believed to be Simonetta Cattaneo de Vespucci, a great beauty and favorite of the Medici court. Apart from being Botticelli’s muse, it is believed she was also his lover.

The Madonna of Macerata

Carlo Crivelli’s muse for the tempera and gold Madonna of Macedrata is not known. On display at the Macerata Musei in Minzoni, Italy, it measures a mere 24- by 16-inches, and yet the power of sideways, pensive glance speaks volumes. Commissioned by the Franciscans and Dominicans of Ascoli, his work was so realistic at the time as to be considered disturbing.

Mona Lisa

She is the most famous woman in all the world of art—La Gioconda, wife of Francesco del Giocondo, better known as Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa . Her faint enigmatic expression and haunting eyes make her thoughts impossible to read. The great master’s use of chiaroscuro and his signature sfumato technique of soft, heavily shaded modeling add to her mystery, and the blurred, imaginary landscape of rocks and water that stretch to the horizon adds even more mystique to Mona Lisa’s graceful figure. So captivating is the portrait, which has hung in the Louvre since 1815, that Mona Lisa has, ever since, received love letters and flowers from her admirers. She even has her own mailbox. The Mona Lisa is an exception rather than the rule. It is doubtful that La Gioconda was Da Vinci’s muse and assuredly not his lover. “He had an almost clinical perception of heterosexual intercourse,” according to historian Elizabeth Abbott. Da Vinci himself wrote, “ . . . the sexual act of coitus and the body parts employed for it are so repulsive, that were it not for the beauty of the faces and the adornment of the actors and the pent-up impulse, nature would lose the human species.”

Girl with a Pearl Earring

She was a milkmaid swathed in an exotic turban and remains one of the most iconic beauties in art to this day. Her identity remains unknown though some believe Johannes Vermeer’s muse was Mary Beghtol, the daughter of Dutch painter Pieter de Hooch. Others believe she was Maria Thinshull, the wife of a merchant, and others say she may have been Vermeer’s daughter. Using a technique similar to Da Vinci and other Northern Renaissance painters, this candid, introspective, emotionless portrait has become known as “The Mona Lisa of the North.”

Ophelia

Portrayed as the drowning Ophelia in Shakespeare’s tragedy, Hamlet, the muse of John Everett Millais is Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862), herself an influential artist, poet, renowned beauty. Among others she was muse of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which included painters William Holm Hunt, Walter Deverell, and her husband, Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Tragically, she suffered from tuberculosis and died from an overdose of laudanum, at the age of 33. “She suffered much from neuralgia, and the laudanum taken to relieve the pain had grown into a necessity,” wrote American philosopher and writer Elbert Hubbard. Though ruled accidental, it is believed “Lizzie,” as she was called—like Ophelia—took her own life.

Madame X

John Singer Sargent caused a scandal when his portrait of the young socialite, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, known as Madame X, was first exhibited at the 1884 Paris Salon. In countless ways, this painting over all Sargent’s others represents beauty in art in the eyes of the artist more poignantly than any he executed. As Sargent was one of the most sought-after and prolific artists of his day, (he painted 900 portraits in oil and 2,000 watercolors) he was commissioned to paint the portraits of some of the most illustrious men and women of the time, including U.S. presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, writer Robert Louis Stevenson, and a bevy of British aristocrats, such as Lady Agnew of Lochnaw. Madame X was the one exception. Sargent chose to paint Virginie, to satisfy his own artistic appetite for beauty. The life-size portrait, which measures 82 by 43.25-inches, consumed two years to complete.

“I have a great desire to paint her portrait and have reason to think she would allow it and is waiting for someone to propose this homage to her beauty . . . you might tell her that I am a man of prodigious talent,” he wrote her family when he determined she would be his muse.

French poet and historical novelist Judith Gautier chronicled the reaction of those who attended the Salon at its opening. “Is it a woman? A chimera, the figure of a unicorn rearing as on a heraldic coat of arms or perhaps the work of some oriental decorative artist to whom the human form is forbidden and who, wishing to be reminded of woman, has drawn the delicious arabesque? No, it is none of these things, but rather the precise image of a modern woman scrupulously drawn by a painter who is a master of his art.”

Perhaps that defines a muse. Is she a unicorn? Forbidden fruit? An ornament? Then again, perhaps it is something much deeper . . . for a muse has an exceptional, spiritual power that can illuminate an artist’s soul—and arouse him to produce his greatest work.

Seated Woman (Dora)

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) was an art movement unto himself and one of the most recognized artists in history. He learned about women at an early age when his father took him to brothels as a means of giving him a solid sex education. In consequence, he was never without a woman, and each was his muse and lover. There were six, all-in-all, who were the most influential: green-eyed, auburn-haired, curvaceous Fernande Oliver, his first great love and muse, who enjoyed making love with him, smoking Opium with him, and being unfaithful to him. His second great muse was Olga Stepanova Khoklholva, a Ukrainian-Russian Ballets Russes dancer whom he married and who bore him his son, Paulo. When she refused to model for him when his work emerged into the Cubist style (she felt it was unflattering to her), he started seeing 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter who got pregnant by Picasso, then 45. The birth of their daughter, Maya, led to his separation from Olga. Picasso and Olga never divorced but after her death, in 1955, Picasso proposed to Marie—and she declined, perhaps because she could not tolerate his frequent philandering. She seemingly couldn’t live without him because four years after his death, she hung herself.

Dora Maar was a tall beauty who became Picasso’s ultimate muse. Very much involved in Left-Wing politics, she herself was a talented painter, poet, and photographer who, it is believed, assisted Picasso in painting his masterwork, Guernica. After Picasso left her, she suffered a mental breakdown and was forced to undergo psychiatric treatment until her death in 1997, of natural causes. However, Françoise Gilot was Picasso’s most famous muse, and lover from 1944 until 1953. but Picasso’s habitual unfaithfulness ended that relationship, even though they had two children together, Claude and Paloma. Jacqueline Roque was working at Madoura Pottery in France, where Picasso created his ceramics, when they met. She was his lover, muse, loyal assistant, and, in a secret wedding ceremony in 1961, his wife. They remained together until his death. Distraught, she slept outside in the snow, lying on his grave, the night he was buried. She committed suicide by shooting herself in 1986—proving that art—and being an artist’s muse—comes at a price.

The Portrait of Wally Neuzil

Wally Neuzil was born in 1894 into a lower-middle class family. She was a paid model to numerous artists, including Gustav Klimt, but when she began modeling for Schiele, Egon fell under her spell, and they became lovers. “She’s not just a model,” observed Diethard Leopold, a major collector of fin de siècle paintings. “She motivated his self-reflection and was a catalyst for his work.” Whatever time they spent together was cut short. Wally died of scarlet fever in 1917, age 23, and Egon failed to reach his full promise as an important artist when he succumbed to the Spanish Flu the following year, age 28.

By Verity Galsworthy