“Any Girl Can Look Glamorous… Just Stand there and Look Stupid”

Doris Day

Doris Day poses in the front seat of her new Oldsmobile convertible in this 1949 snap.

IN THE CONSTELLATION OF STARS that illuminated Hollywood’s silver screen after World War II, none sparkled quite like Doris Day’s. Her comparatively short film career spanned only two decades, but she made 39 major motion pictures and played opposite some of Hollywood’s greatest leading men—Clark Gable, James Stewart, Frank Sinatra, James Cagney, and many others. But her favorite co-star and one of her closest friends was Rock Hudson, who, like Doris, warily guarded his private life. He starred with her in three movies, and they remained devoted to one another until Hudson’s death in 1985 from AIDS at age 59.

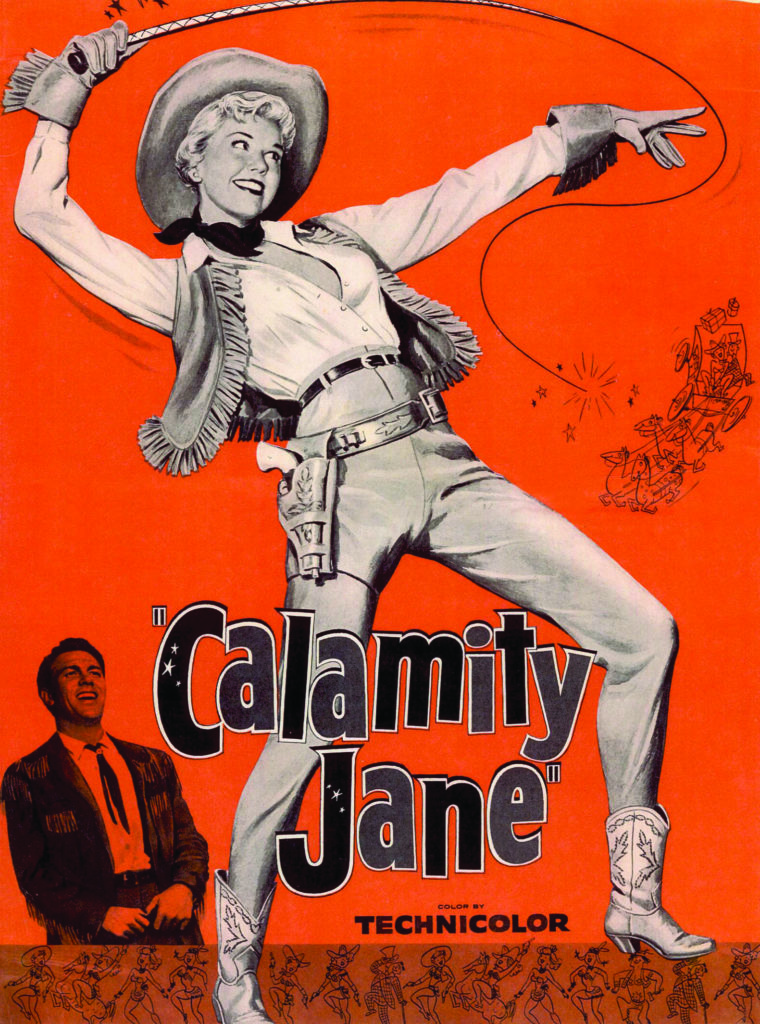

Doris Day’s film career began when she was 25 (though she professed, and appeared, to be two years younger.) She had been touring with the Les Brown Band when songwriter Jule Styne and his partner, Sammy Cahn, heard her rendition of the Gershwin classic, “Embraceable You.” They were so impressed that they recommended her for a role in the musical film, “Romance on the High Seas” (1948). Like a comet, she shot to stardom in a rapid succession of box office hits, making at least two major motion pictures a year—in 1961, five—including “Calamity Jane” (1953), “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1956), “Teacher’s Pet” (1958), “Pillow Talk” (1959), “Please Don’t Eat the Daisies” (1960), and “With Six You Get Eggroll” (1968).

Acting came naturally to Doris. Hungarian-born American director Michael Curtiz (“Casablanca,” “Mildred Pierce,” “White Christmas”), who directed Doris in the musical “I’ll See You in My Dreams” (1952), told her never to take acting lessons, so pure was the innate gift, raw honesty and unpretentious charm she brought to the screen. She was best known for her comedies yet was equally admired for her dramatic roles. Her films were among the Top 25 box office hits 19 times and No. 1 four times, in 1960, 1962, 1963, and 1964—more than any actress in Hollywood history. She sang “Que Sera, Sera” in Alfred Hitchcock’s suspense thriller, “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” winning the 1956 Academy Award for Best Original Song and a Columbia Gold Disc for over a million record sales. Translated “What will be, will be,” it became Doris’s theme song in her television series, but more than that, it defined her attitude in life.

In 2004, she was bestowed the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush, and in 2011, approaching the age of 90, she released her 29th and final album, “My Heart,” one of the best-selling albums of 2011 and ranked ninth in Great Britain among the Top 40.

And yet, unlike the Doris Day the world knew onscreen, Doris Day’s personal life was besieged with disappointment, tragedy, and unremitting sadness.

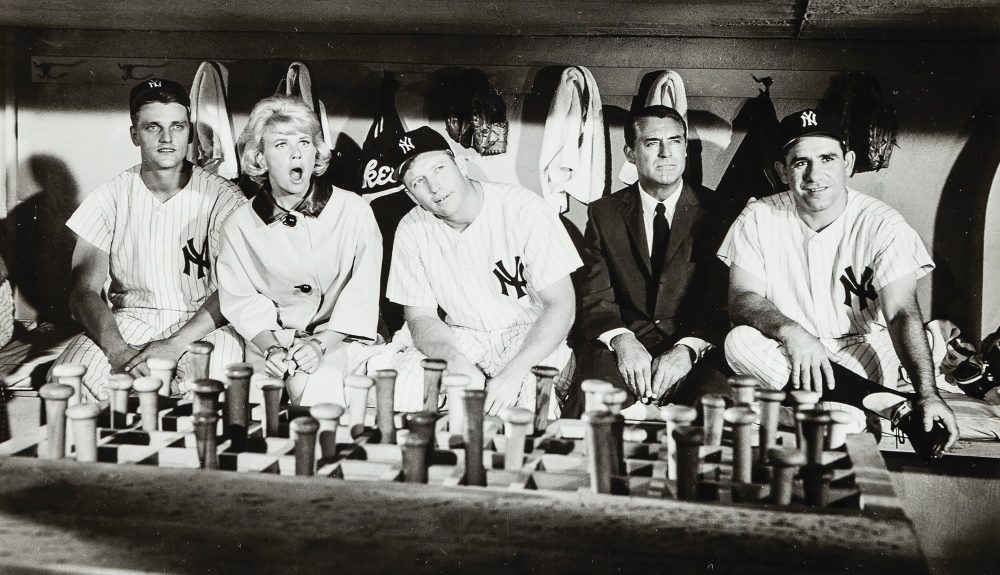

Doris Day stared with Cary Grant in ‘A Touch of Mink’. They are in the dugout with Yankee players, Roger Maris, Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra.

America’s Sweetheart

Sing, dance, act in comedy or drama, on the radio, in the recording studio, in films or on television, Doris Day could do it all. She was “America’s sweetheart,” “the girl next door,” as wholesome as home-baked bread, as chipper as a lark, with a dazzling smile that could dissipate a storm cloud.

Doris Day in ‘Calamity Jane ‘ in1953

Nonetheless, she would confess in her 1976 memoir, “Doris Day: Her Own Story,” “I’m tired of being thought of as Miss Goody Two-Shoes. I’m not the All-American Virgin Queen, and I’d like to deal with the true, honest story of who I really am.” She never would realize her greatest dream, and is quoted in “American Legends: The Life of Doris Day” by Charles River Editors: “All I ever wanted to do was get married, have a nice husband, have two or three children, and have a nice house and cook.”

She found her real happiness in her only child, son Terry Melcher, a successful record producer, singer, and songwriter who predeceased his mother by 15 years when he died in 2004 at the age of 62 from melanoma. “Not only was Terry my son, but he was also my buddy for all of his life,” Doris mourned.— “American Legends: The Life of Doris Day” by Charles River Editors.

“That kind of saddens me a little bit about her life, that she couldn’t really be herself publicly because she had a lot of sadness behind the scenes,” observed Australian country singer and songwriter Melinda Schneider, who performed her one-woman tribute concert, “Doris Day: So Much More Than the Girl Next Door,” to sell-out audiences at the Sydney Opera House and recorded a No. 1 best-selling album, “Melinda Does Doris.” “She had four tumultuous marriages and a lot of tragedy in her life. But no one ever knew about it. That was always the secret.”

Indeed, it was her inherent perseverance and positive attitude that kept Doris from succumbing to the crushing lows and blows that would have destroyed most people. She put it like this in her memoir: “No matter what happens, if I get pushed down, I’m going to come right back up. I’ve been through everything. I always said I was like those round-bottomed circus dolls—you know, those dolls you could push down and they’d come back up? I’ve always been like that. I’ve always said, ‘No matter what happens, if I get pushed down, I’m going to come right back up.’”

Childhood

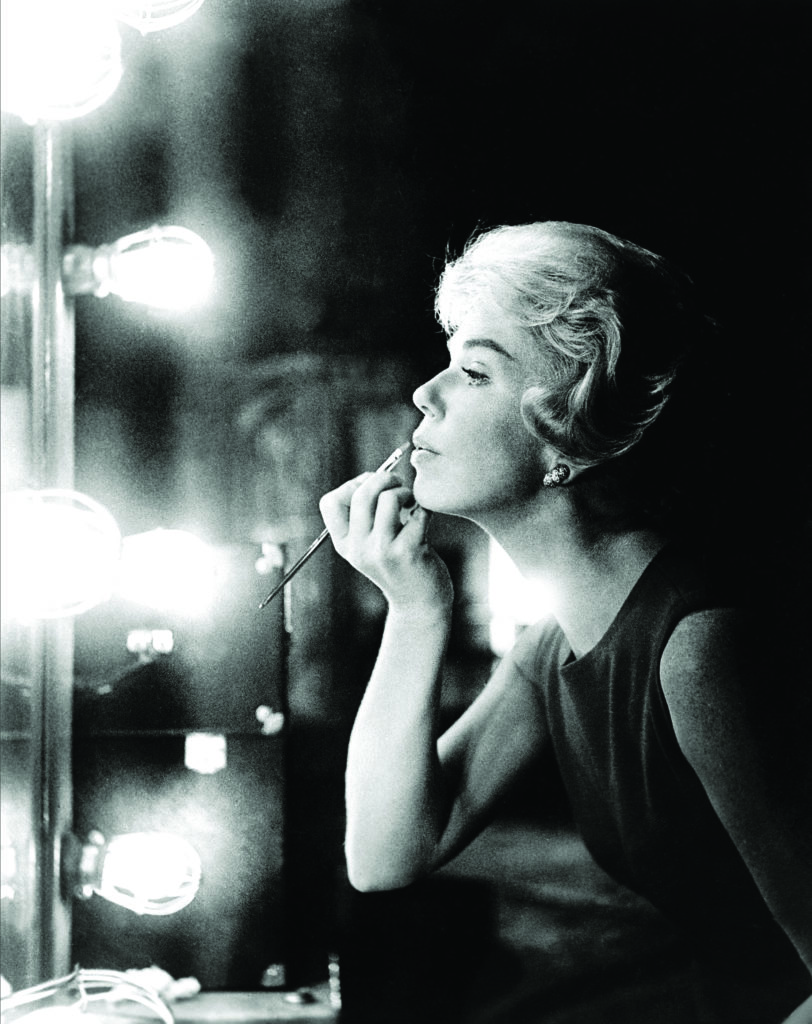

Doris Day recording studio about 1960

Doris Mary Anne Kappelhoff was born April 3, 1922, the youngest of three children of first-generation German-Americans Alma Sophia Welz (1895-1976) and William Joseph Kappelhoff (1892-1967), whose respective parents emigrated to America around 1875 and settled in the densely populated German quarter of Cincinnati. She was named after her mother’s favorite actress, silent movie star Doris Kenyon, Rudolf Valentino’s on-screen paramour.

The Kappelhoffs lived in a red duplex on the corner of Jonathan Street and Greenlawn. Doris had two older brothers: Richard, who died in childhood before Doris was born, and Paul, who was three years her senior. The Kappelhoff and Welz families were neighbors and friends, and the marriage between Alma and William was likely arranged, as was common among old European families in those days. Doris’s father, William Joseph Kappelhoff (1892-1967), was a classical music professor and the church organist and choirmaster at St. Mark’s Catholic Church, where the family faithfully attended Mass. William was an introvert who immersed himself in Mozart and Beethoven. His wife, on the other hand, was a vivacious extrovert who loved jazz, swing, and especially the “new sound” Jimmie Rogers brought to country music. Alma loved dancing, parties, and hanging out at the local beer garden to eat, drink, and dance with friends to the lively live music while her husband remained home with the children and played Bach on his gramophone. Husband and wife could not have been more different.

Doris was a sensitive and high-strung child who must have sensed the disparity between her parents. Creative and imaginative like her father, she was happiest in her own company and spent much of her time playing alone. But those carefree childhood days were cut short when Alma, obsessed with Hollywood, determined to make Doris a star. Doris loved to dance, and when she was 5 years old, Alma enrolled her in dance school. Doris was the youngest girl in her class and was shy and nervous at the beginning. When she went on stage to perform in her first dance recital, she became so anxious that she wet her pants. As she twirled around, the audience tried to suppress their laughter at the large wet spot on the back of her red satin skirt. Undaunted, Doris persevered, finishing her routine with a ladylike curtsey before running offstage weeping into her mother’s arms. But something inside of her must have been sparked by the audience’s thundering applause. She was never shy and nervous in front of an audience again.

Alma enrolled her daughter in more classes—tap and ballet, piano lessons, and acrobatics, in which she excelled. She took speech lessons. She entered contests, always winning, spurring her mother to keep pushing. Alma took in sewing jobs at night to pay for lessons that cost more than her husband’s meager income could provide. Doris was now the main focus of her mother’s life—to the exclusion of her husband. William became more distant and absent.

When Doris was 8, she overheard her parents violently arguing. William was caught having an affair, but the blow struck even harder when it was revealed that “the other woman” was Alma’s best friend. The scandal became public, and William was fired from his teaching position and kicked out of the church. He packed his bags and said goodbye to his son, Paul, but not to Doris, which troubled her the rest of her life. The divorce became final in 1936.

To his credit, William did not disappear entirely from his children’s lives. Every Wednesday, he would bring Paul and Doris to his sister’s house for a large family dinner. “I had a wonderful family, including aunts, uncles and cousins,” Doris would reminisce in her autobiography, looking at the bright side—as always.

Doris Day with good friend, Rock Hudson. The pair made many movies together.

Now a single mother, Alma moved her children to a small apartment and got a job at a bakery, and the children went to school. One of Doris’s classmates was a boy named Jerry Doherty, who also was 12 years old and loved to dance. The youngsters formed a dance duo, began performing and became a local sensation. In 1937, when they were both freshmen at Our Lady of Angels High School, they entered a dance contest sponsored by a department store. For weeks they rehearsed, and Doris and Jerry beat more than 500 other teams to take the first prize of $500—almost $10,000 in today’s money. That spring, Alma and Jerry’s parents set out for Hollywood with their children to pursue their careers.

As soon as they arrived, Alma arranged for Doris to take lessons from the famous American dancer and choreographer Louis DaPron, who coached, among many Hollywood musical stars, Donald Connor (“Singing in the Rain”) and later became head choreographer at Universal Studios. A Paramount Studios talent scout noticed Doris and wanted to arrange a screen test for her, but Doris was committed to Jerry and refused. Her steadfast loyalty would define her friendships throughout her life.

That October, the families decided to move permanently to Los Angeles to pursue their children’s promising careers. They returned to Cincinnati to sell out and pack up for good. The night before returning to L.A., mutual friends from nearby Hamilton threw them a farewell party. Doris would drive out with Jerry’s brother, Larry, and another couple their age. It was raining hard, and fog began to settle. By the time they came upon a railroad crossing, the fog was so thick that the driver saw the lights of a fast-approaching train too late. The train crashed into the car, catapulting the driver and the front-seat passenger, Marion, through the windshield and Larry from the back seat. Remarkably, no one was seriously injured but Doris, who was trapped in the wreck and sustained two compound fractures in her right leg that would require steel rods to be inserted from her thigh to her toes. The doctors hoped she would walk again. Doris knew she would dance. However, dreams of Hollywood were crushed . . . for now.

The families reestablished their lives in Cincinnati. Jerry returned to high school and Doris recovered at home. Four months stretched to 14 when, toward the end of her recovery, she caught her toe on the living room carpet, fell, and refractured her leg. Bedridden, she sang along to the big band sounds of Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller, and Tommy Dorsey on the radio. But the voice she loved listening to best was Ella Fitzgerald’s. Ella had a clean, clear, crisp voice like no other singer.

Alma decided her daughter needed to take singing lessons. Through a friend in the music business named Danny Engel, an audition was arranged with professional vocal coach Grace Raine. After hearing Doris sing, Raine told Alma that Doris lacked sufficient talent. But Alma persevered, and Raine agreed to give Doris a chance. The teenager’s desire to learn and dedication to her training enabled Raine to transform her young student, and Doris rapidly became her best pupil. Aware that Alma was sewing at night to pay for Doris’s lessons, Raine charged her for only one lesson out of every three. Years later, Doris would credit Raine for cultivating the voice that would thrill untold millions.

Doris Day makes a phone call in the garden at her home in Toluca Lake, Los Angeles, California, circa 1955. (Photo by Phil Burchman/Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

The Road to Fame and Fortune

“I’m still Doris Mary Anne Kappelhoff from Cincinnati. All I ever wanted to do was get married, have a nice husband, have two or three children, and have a nice house and cook. I ended up in Hollywood. If I could do it, you could do it. Anyone can do it.”

When she was 14, Doris and her mother moved into an apartment over her Uncle Charlie’s bar, Welz’s Tavern, at 3113 Warsaw Ave., Cincinnati. The personable teenager sang along with the jukebox, entertaining the customers as she served her aunt’s famous 15-cent barbeque sandwiches. At age 15, she landed a gig singing at Charlie Yee’s Shanghai Inn, a popular local restaurant, where she earned $5 a night. When she was 16, she landed her first professional job performing as a vocalist on the popular WLW radio show, “Carlin’s Carnival.” That’s how bandleader Barney Rapp, who was looking for a female vocalist, discovered her. He sought her out and asked her to audition, but she was up against 200 other singers. She won the audition and began traveling all over the country as the lead singer of Barney Rapp and the New Englanders. Early on, Rapp told Doris that Kappelhoff was too long a name for a billboard or marquee. Loving how she sang the popular song, “Day After Day,” he suggested she change her surname to Day—and Doris Day was born.

The band’s trombonist, Al Jordan, courted her, and Doris fell in love. They married, left the band, and moved to New York City to broaden Al’s prospects, and there Doris gave birth to Terrance P. Jordan (who later would be adopted by Doris’s third husband, film producer Martin Melcher, and would take his stepfather’s last name.) The marriage was short-lived. Al Jordan had a terrible temper and was abusive. Doris, an 18-year-old divorced single mother, would then return home to Cincinnati and move back in with her mother. Alma took care of the baby while Doris got work, but the occasional gig was not enough. Doris moved, alone, to Chicago to pursue her career.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

“I like joy; I want to be joyous; I want to have fun on the set; I want to wear beautiful clothes and look pretty. I want to smile, and I want to make people laugh. And that’s all I want. I like it. I like being happy. I want to make others happy.”

Television

Though Doris was first seen on television at the 21st Annual Academy Awards telecast in 1949, and afterward, in various shorts, and with Bing Crosby on “The Bob Hope Show” in 1950, her first standalone television appearance was in 1954, when she was the mystery guest on the popular show, “What’s My Line.” It was on that show that she was presented with a gold record for selling one million recordings of “Secret Love,” first sung by Doris in “Calamity Jane” (1953), and which won an Oscar for Best Original Song that year—one of three Academy Award nominations for songs she introduced in films.

However, Doris never had any desire to act on television. In fact, she loathed the idea. She was a film star, and that was the environment that suited her best. What’s more, she had created her own brand of romantic comedy. After she made her last major motion picture, she decided to leave Hollywood and dedicate the rest of her life to animal welfare. She moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea, only to discover a detour along her chosen path.

Her third husband, Martin Melcher, died in April 1968 at age 53. He had managed Doris’s career since their marriage in 1951, and she, happily, left all the business dealings to him. However, he was not forthright with her on how he was handling her substantial wealth. It was, therefore, a terrible shock after his death to discover the true state of her affairs. Without her knowledge, Melcher had signed Doris to star in her own television series, “The Doris Day Show.” She was incredulous, angered, but true to form, knew she had no choice but to honor the commitment. She only learned of this when her son, Terry, stepped in to take care of Doris’s financial matters. Not only was Doris bankrupt, but she also was half-million dollars in debt.

After the shock subsided she looked her misfortune squarely in the face. “Gratitude is riches,” she said. “Complaint is poverty.”—“American Legends: The Life of Doris Day” by Charles River Editors. From the first moment she walked on the set, Doris gave it her all; as always, she was a true professional. She even did the set design for the series’ home interiors.“The Doris Day Show” became an instant hit. One of the most popular shows on television, it aired on CBS for five seasons, from September 1968 to March 1973, with 128 episodes. After the series ended, Doris quit acting for good. She would appear infrequently on television and occasionally for interviews on “The Merv Griffin Show,” “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson,” and “The Mike Douglas Show,” where she would promote her dog charity.

A Mother’s Instinct

It was during this time that Doris faced one of the most terrifying incidents of her life. Mike Love, who co-founded the Beach Boys with Dennis Wilson, wrote about the attempted murder of Terry Melcher in his New York Times best-selling autobiography, “Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy.” (Blue Rider Press, 2016.) In 1968, Terry Wilson had introduced Melcher to cult leader Charles Manson, who had visions of becoming a rock star. Terry, now an established record producer, was shaping West Coast music with hits such as The Byrds’ “Mister Tambourine Man” and “Turn, Turn, Turn.” But Melcher didn’t think Manson had any future in rock—news Manson did not take well. In his book, Love wrote, “Terry had told his mother, Doris Day, about Manson—and about some of his scary antics, his brandishing of knives, his zombie followers, and that Manson had been to the house on 1050 Cielo Drive (that Terry had been sharing with his then-girlfriend, actress Candace Bergen) and Doris insisted he move out.” They did, and the owner leased the Cielo Drive house to director Roman Polanski and his eight-month-pregnant wife, actress Sharon Tate. What happened soon after, on August 9, 1969, is one of the most savage criminal acts in modern history: Tate and four other people were murdered in the Cielo Drive house.

Doris admitted she had had a dreadful foreboding that led her to plead with Terry and Candace to move out of the ill-fated house. Love called it “a mother’s intuition.”

There were several suppositions: the mass-murder was targeted as revenge against Terry Melcher and that Manson was unaware that he and Bergen had moved out. Susan Atkins, a member of the Manson family, admitted her part in the slaughter and stated to the police and before a grand jury that the house was chosen to instill fear in Melcher.

After the tragedy, Melcher moved in with his mother. He later served as the executive producer of her television series, “The Doris Day Show,” co-produced “Doris Day’s Best Friends,” which spotlighted pets and their owners, served as vice-president of the Doris Day Animal Foundation, and co-owned the Cypress Inn in Carmel, California.

Tragically, Terry’s life ended after a long battle with melanoma. He was 62 when he died at home on November 19, 2004, with his son, wife, and mother by his bedside. Only once, after her son’s death, did she allude to her loneliness. “If so many people love me, how come I’m alone?”—“American Legends: The Life of Doris Day” by Charles River Editors.

Home at last

In the early 1980s, Doris sold her contemporary-style home in Beverly Hills and left Hollywood for good. “I really loved being there, but then I started to notice that it was changing,” Day would later reveal in an interview. “It really started to change, and, oh, people were moving away because strangers from foreign countries were all over on the street and tearing the beautiful houses down and putting up boxes. I really wasn’t happy about that at all. Wasn’t the town I knew.”

She made her home a sunny, yellow-and-white, country-style house perched high above the Quail Lodge Golf Course in Carmel-by-the-Sea. The décor was charming, the overstuffed sofas and chairs were arranged around a huge fireplace, and there was a lot of wicker—she loved wicker—with a few poppy-red accent pieces strategically placed to break up the whiteness—most prominently, the red-painted piano her son, Terry, had given to her as a gift. Schumann Bavarian china, Wallace sterling silver flatware (a gift from her mother), and Waterford crystal were set on her Louis XV style dining room table whenever she entertained, which was often. The house was clean and uncluttered.

It was here, surrounded by a few close friends and her 14 dogs, that Doris Day succumbed to pneumonia on May 13, 2019. Her final wish was to have no funeral, no memorial service, and no grave marker. And perhaps that was unnecessary. After all, she left her true mark in the happiness her films and music have given countless millions and will continue to provide. Almost a year later, on April 4, 2020, the contents of the house, including her four Golden Globe awards, went under the hammer of Julien Auctions. The property was sold. Estimated at $200 million, all the proceeds went to Doris’s beloved animal foundations.

In 1974, Doris joined Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, Kirk Douglas, Ronald Reagan (then governor of California) and a host of other celebrities in presenting the AFI Life Achievement Award to the late, great actor James Cagney, with whom she appeared in “Love Me or Leave Me.” Doris said, “You’re more than just an actor. You don’t play the character; you live the character. You breathe life into your own performance and make the rest of us really look good. That’s because you’re there. And tonight, you make the whole world feel good just because you’re here.”

We could say the same about you, Doris, because through good times and bad, you made the whole world feel good—just because you were here. “I love to laugh, The Life of Doris Day” would quote her saying. “It’s the only way to live. Enjoy each day—it’s not coming back again.” ■