Nothing strikes fear into the heart of an art collector or museum like the possibility that a prized work of art might be a worthless forgery. And yet, despite the best efforts of experts to safeguard against them, fake works masquerading as priceless originals continue to plague the market and have been eroding buyers’ trust in the art industry for decades. And while many believe this to be a fringe occurrence of only a few instances, new analyses and extrapolations paint a much darker picture of the problem.

According to a report by the AFP, Geneva-based Fine Arts Expert Institute (FAEI) chief Yann Walther estimates that 50% of art circulating on the market has been forged or misattributed, and these numbers are likely on the conservative end of the spectrum. Some sources estimate the number to be as high as 70%. The sheer ubiquity of shams is often linked to the continuously increasing demand in the billion-dollar art industry, which far exceeds the limited supply, particularly in the case of highly sought-after blue-chip art as well as the lack of transparency and regulations.

And although history is rife with high-profile art scams, the surge in the last 20 years has reached epic proportions, blindsiding some of the most trusted art institutions and museums and toppling over the reputational pillars of a multi-billion dollar industry.

The ingenuity of these forgers has not only baffled the public, continued to fool art experts and evade authorities alike sometimes for decades, it has also evolved with technology. According to experts, the problem has only grown since the advent of the internet. A recent New York Times article details how there has been a significant increase in the production of fake prints sold online targeting unsuspecting buyers. Forgers have been able to take advantage of advancements in photomechanical reproduction with modern technology to create counterfeit artworks, including works by renowned artists such as Warhol and Lichtenstein.

One of the most high-profile cases in Europe, Wolfgang Beltracchi caused one of the greatest art scandals in history and shook the art world to the core, and his ability to deceive even the most seasoned professionals in esteemed auction houses and museums raised perplexing questions of authenticity and the inherent superiority of original art. With the widow of Max Ernst supposedly calling one of his forgeries of her husband, The Forest (2), “the most beautiful picture Max Ernsthad ever painted,” and Beltracchi openly boasted that he could mimic and even improve upon the style of any original artist who ever lived. He also claimed that he could never expose all of his works currently exhibited in museums worldwide without causing complete chaos. So how was it possible for one man to forge works at this scale and only get caught years into this scam due to his use of a certain white paint that had a chemical in it that did not fit the alleged time period?

His methodology involved meticulously scouring historical records for pieces that were attributed but never described or pictured anywhere. His guiding principle was to stay reasonable in never forging pieces over a six-figure value from artists like Max Ernst, Georges Braque and Fernand Léger. Utilizing old paintings from flea markets dating back to the appropriate era of his intended forgery, he would painstakingly strip away layers of paint and repurpose the cavasses and the aged dust preserved within. To get his desired finish, he confessed to baking his paintings in a standard oven until they looked aged. He then fabricated a provenance – a term used to refer to the ownership background of every artwork – and went ahead to forge papers and gallery labels to go with this story, even going as far as dressing up his life partner as the supposed grandmother they inherited the pieces from and faking an old picture of her sitting next to the artwork in question. He knew of not only the importance of creating a seamless proof of ownership, but also the need to use paint with a certain chemical composition to fool testing. (The one that got him caught did not show the “smoking gun” chemical in the description.) He knew the penchant of experts to look for tell-tale labels on the back of the frame by known dealers and the need for authentic “dirt” stuck at the back of the painting. This calculated approach allowed him to offer convincing pieces with an astonishing level of background information and chemical authenticity, claiming to have found a long-lost treasure at their grandmother’s attic.

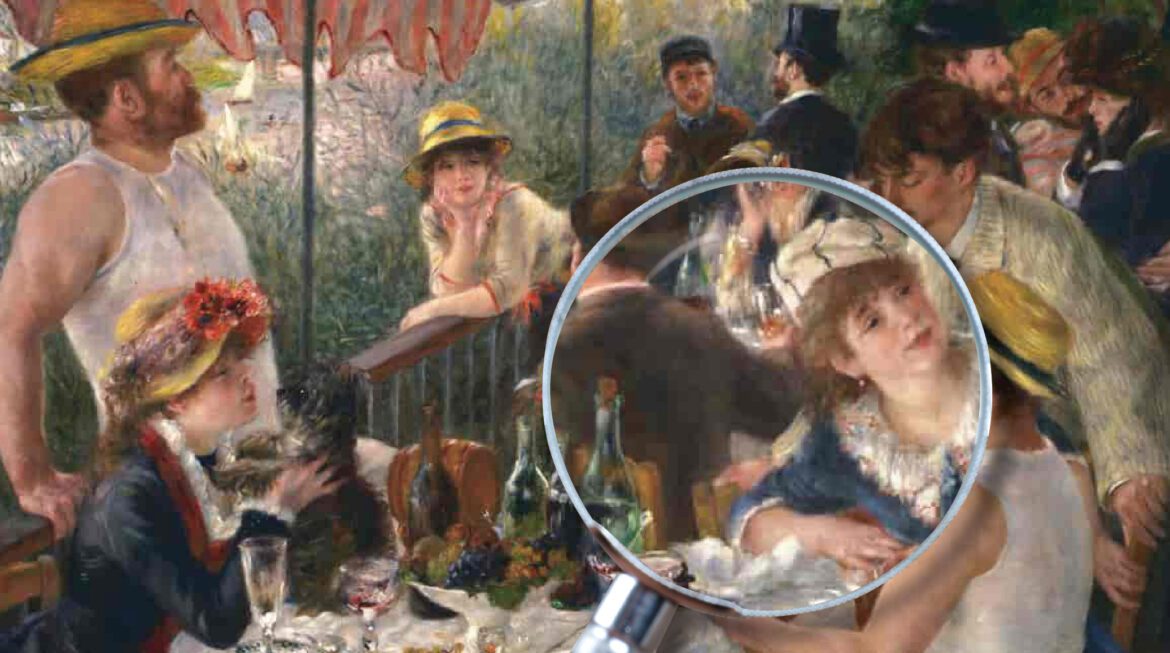

This principle of matching “lost pieces” with an existing provenance proved very lucrative for famous French art forger Guy Ribes and his accomplices. Considered to be one of France’s most famous art forgers, he started creating counterfeit paintings in the mid-1970s by simulating the styles of great masters such as Matisse, Renoir, Modigliani and Chagall, and also using materials and paints from the period in which the original pieces would have been created. The trick in this case was that the papers (certificates by major authenticating authorities, old invoices and estate photographs) were real but the piece matching the papers had been switched.

The unsettling reality of these prominent cases is not only that counterfeiters can sometimes produce better replicas than the original, making quality and style unreliable indicators of authenticity, but also the fact that the use of aged materials can confound chemical analyses, and even the provenance of artworks can be forged, with counterfeit pieces specifically created to align with stolen or falsified paperwork.

So, how can novice art buyers protect their investments and exercise caution when purchasing artwork?

A first step is to avoid “private sales” and backyard markets with low or limited attention from authorities, and instead opt for vetted art fairs where every piece of art entered undergoes extensive screening by experts. Another way of securing your purchase is to buy from secondary market dealers who employ a team of researchers carefully checking the background and publication records and guaranteeing the authenticity at their own risk as a legal entity, a guarantee which most auction houses sidestep in their fine print. When buying from an auction house, it is prudent to request a condition report, a chemical analysis (if available) and to ask for any sort of documentation or paperwork accompanying the piece (usually provided upon sale), along with the return policy and conditions should the piece turn out to be fake. Any provenance provided by dealers or auction houses should be supported by thorough documentation (“found in grandma’s attic” does not suffice), including paperwork and, ideally, a respected publication – exhibition catalogs, published sales records, and verified photographs of the estate are commendable. It is important to note that the existence or lack of documentation is very common and does not mean the art is necessarily fake; however, lack of authenticity, publication and previous ownership records have a significant impact on the resale value and usually lead to unpleasant surprises upon reentering the piece into the market.

Additionally, it is always wise to conduct a search online, cross-checking all provided information against available databases (i.e. ArtNet.com, ArtPrice.com, ArtLoss.com) to see if the artwork has previously been offered at a public auction and been brought in or withdrawn, as this could signify potential issues. Researching these databases for similar artworks and comparing pricing is a helpful tool, since suspiciously low prices are often designed to attract undiscriminating novice buyers.