Trude Schonthal Heller

Holocaust Survivor & Philanthropist

1922-2021

“My favorite word is ‘love.’ My least favorite word is ‘hate.’”

—TRUDE

Read publisher, Karen Floyd’s interview with Trude Heller from 2016

Trude Schonthal Heller, 98, died on May 11, 2021. A survivor of the Holocaust, the woman who gave inspirational speeches to thousands of men, women, and children preferred to refer to herself as a “Holocaust educator.” Born in Vienna, Austria shortly after World War I, the former First Lady of Greenville, South Carolina, could not have become the philanthropist and community leader she was had she not lived through one of the darkest periods in history—the genocide of more than six million European Jews by Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany in World War II.

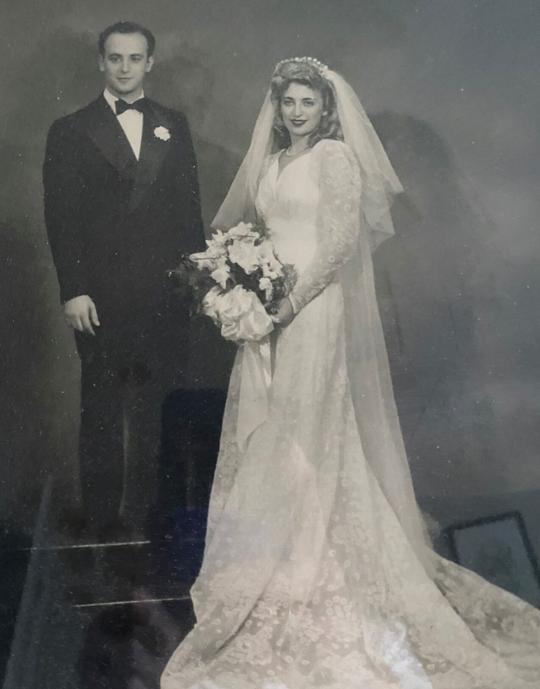

Trude and her parents emigrated to America in 1940, a year before the United States entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. She and her husband, Max, married in Greenville in 1941 and raised their two daughters, Francie and Susan, and son Steven, nurtured ten grandchildren, and welcomed 19 great-grandchildren. Her large family was her greatest source of pride and, she often said, “my answer to Hitler.”

“My children are in New York, Ohio, and California, but we are a very close family and get together as often as we can.” Trude met Max when she was 14 and he was 17 at a resort outside of Vienna, where both families spent summers. She didn’t love him when they first met, but the first time they met, at a dance, he told her, “I am going to marry you.” By the time of his death in 2011, the couple had been married 69 years.

The only daughter of Austrian-Jewish merchants Simon and Rose Schonthal, Trude was born June 19, 1922, in Vienna. “My parents they called me sitzen,” she laughed in an interview five years ago with Karen Floyd, founder and publisher of Elysian. “Sitzen means, ‘sit still’ in German, and I did! I did everything my parents told me to do, I was such a good girl. Wherever they sat me, that’s where I sat. I didn’t know any better. I had no brothers or sisters.

“My father owned two stores in Vienna that catered to tailors. There was no such thing in Europe in those days as ready-made suits. Most tailors in this country come from Europe even today. All the tailors in Vienna shopped at my parents’ stores. There are 36 things used to make suits. My mother loved to work, and she helped my father at the stores, but she was also the best cook and baker in the world. She could take a little piece of dough and roll it out over a table that seats 12 and never would the pastry tear.” However, it was her maternal grandmother, who died when Trude was 12, she credits as her greatest influence. “She was wonderful. She loved life. On her tombstone is chiseled, Unser Alles—our everything. She is always with me.”

“It was the night they broke a lot of glass to get the people and kill them,” she recalled. “There was a young man in France whose parents were killed, and he killed a German attaché, and Hitler gave the people 36 hours to do as they wanted with the Jews, especially the men. Thousands disappeared.”

The pretext for the pogroms (massacre) was the assassination of German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in Paris on November 7, 1938, by Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jewish student. When news of Rath’s death reached Adolf Hitler in Munich, Germany two days later, he ordered reprisals to be conducted by German storm troopers throughout Germany, which at that time included Austria.

“In shortest order, actions against Jews and especially their synagogues will take place in all of Germany,” Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller ordered by telegram to all police units, “These are not to be interfered with.”

In the two days and nights of Kristallnacht, as the “night of broken glass” was called, more than 1,000 synagogues were razed, 7,500 Jewish-owned businesses were looted and the premises destroyed, Jewish hospitals, homes, schools, and cemeteries were vandalized. Over 30,000 Jewish men between the ages of 16 to 60 were arrested, taken to Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen, never to be seen by their loved ones again. “The swine won’t commit another murder,” Nazi Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring remarked.

Trude had been on her way to the gym. The flags of Christian Democrats, Social Democrats, and others declared the people’s allegiance to their party. When she came out of the gym, the entire city was covered in swastikas and all the police had a swastika band on their arm. “They marched into Vienna,” Mrs. Heller recalled. “Father wanted to leave, mother did not.” From that day forward until the end of World War II, the Nazi regime made Jewish survival in Germany impossible and Trude’s carefree and privileged life was over.

“We lost our home and had to move to a fourth-floor walkup in an old house but we were happy to have it. One day, my father went out to get some items from the store he thought he could sell. He returned right away. ‘A man is waiting to arrest me is downstairs,” he said. He has allowed me a few minutes to say goodbye before they take me away.’ Immediately my mother went to a neighbor, a Jewish woman, who had a son who wasn’t right. ‘Would you hide my husband?’ she asked, and the neighbor said yes and hid him in a closet.

“After the Nazi soldiers left, we put my father on the floor of a cab and the driver, who did not give my father away, took him to the train station. He got on the train and called a waiter over to him. ‘I have money if you hide me under the table.”

Her father made his way to Belgium and safety. It was many months before Trude and her mother, after their long arduous, and dangerous escape to Belgium were reunited as a family.

“An act of kindness—yes,” Mrs. Heller said in her interview. But there were not so many acts of kindness—not enough—during that time. There could have been more. During those five years, there were people helping us. But couldn’t understand how there could be so many who did not. I made up my mind then that I wanted to be better than them. That’s why I have made it my purpose ever since to help people as much as I can.” Despite the early, dark chapter in their lives of the Holocaust, Max and Trude enjoyed a wonderful life. Having known too well how fleeting life can be, theirs was a 69-year-long partnership and love affair. “Sunday morning, they would dance to music in the house,” their daughter, Francie, reminisced. “I grew up with two parents who really went through a lot and were refugees who came to America and to Greenville with nothing. But they always taught us that there was good in people. My father used to say, ‘I believe in miracles. I just don’t rely on them.’

“They tell stories about people that come from other countries and are never happy, they talk about what they lost. We never did that. We were so grateful for everything. My parents came, by another miracle, Max’s parents came by a miracle. So, we are very lucky.

“I cannot figure out man’s inhumanity to humanity,” Trude puzzled throughout her life. “Love, don’t hate. I taught my children what I call the ‘echo effect.’ Five years found people helping us and couldn’t understand how can there be so many who don’t I made up my mind then that I wanted to be better than them.

“Man’s inhumanity to man, it starts in school with bullying. Unfortunately, there are countries that have so many people. Who are the people who can do these things? Where does ISIS come from? What kind of human beings are these?

“Talk sweet and all of a sudden people talk sweet to me. It works. Not always, of course, but more than not.

“We decided when we started that our children would have a lot of hope and you know, it works when you set your mind to something. We had nothing. We were refugees, but we were happy. We were thankful for things rather than bemoan what we didn’t have.”

Trude believed in strength in marriage. “We discussed most everything. We argued sometimes and very often I would have to say, ‘you are right’ or he would say, ‘you are right.’ We did everything together. We learned together when we came to this country—we didn’t speak English—and we were lucky. Not many marriages are like that.”

“I love my country. When I can back to fly to Austria, they look at my passport and see that I was born in Vienna. “Oh, you came home,” the Customs Officers say. “No, sir,” I reply. “I’m going home.”

As Trude neared the end of her life, she pondered “whether to believe there is something after life or not. But I believe my husband was right when, just two weeks before he died he told me, ‘I need you with me.’

“I did a lot in my life. I am really very lucky. I have no regrets. It’s all come out good.”

A fitting tribute by those who knew and loved Trude Heller would be precisely the words marking her beloved grandmother’s grave:

UNSER ALLES. OUR EVERTHING

MARRIAGE & MIRACLES

Despite the early, dark chapter in their lives during the Holocaust, Max and Trude enjoyed a wonderful life together. Having known too well how fleeting life can be, theirs was a devoted 69-year-long partnership and love affair. They believed in strength in marriage.

“We discussed most everything. We argued sometimes and very often I would have to say, ‘you are right’ or he would say, ‘you are right.’ We did everything together. We learned together when we came to this country—we didn’t speak English—and we were lucky. Not many marriages are like that.”

“Sunday morning, they would dance to music in the house,” their daughter, Francie, reminisced. “I grew up with two parents who really went through a lot and were refugees who came to America and to Greenville with nothing. But they always taught us that there was good in people. My father used to say, ‘I believe in miracles. I just don’t rely on them.’”

Mrs. Heller would likewise observe, “They tell stories about people that come from other countries and are never happy, they talk about what they lost. We never did that. We were so grateful for everything. My parents came, by another miracle, Max’s parents came by a miracle. So, we are very lucky.

Helping others

“I cannot figure out man’s inhumanity to humanity. Love don’t hate. I taught my children what I call the ‘echo effect. Talk sweet and all of a sudden people talk sweet to me. It works. Not always, of course, but more than not.

“Man’s inhumanity to man, it starts in school with bullying. Unfortunately, there are countries that have so many people who do harm. Who are the people who can do these things? Where does ISIS come from? What kind of human beings are these?

About hope

“We decided when we started that our children would have a lot of hope and you know, it works when you set your mind to something. We had nothing. We were refugees, but we were happy. We were thankful for things rather than bemoan what we didn’t have.”

Love for her adopted country

“I love my country. When I can back to fly to Austria, they look at my passport and see that I was born in Vienna. “Oh, you came home,” the Customs Officers say. “No, sir,” I reply. “I’m going home.”

The life after death

As Trude neared the end of her life, she pondered “whether to believe there is something after life or not. But I believe my husband was right when, just two weeks before he died he told me, ‘I need you with me.’

“I did a lot in my life. I am really very lucky. I have no regrets. It’s all come out good.”

A fitting tribute by those who knew and loved Trude Heller would be precisely the words marking her beloved grandmother’s grave: UNSER ALLES. OUR EVERYTHING