Throughout art history, there have been female figures whose heroic imagery has echoed through time with unparalleled impact. Two of them, the Egyptian queen Berenice II and the fictional heroine Antigone, have inspired artists over the course of millennia and resonated within our culture to an extent that seemingly every art epoch had to have its own interpretation of these symbolic women. And since it has been postulated that it is hero figures that formulate our concept of exemplary leadership and ideal social conduct, the depiction of these heroines is more than a call to memory of a defining set of values; their particular interpretation also singles out the characteristics of each century (and the respective artist becomes the interpreter of their manifestations).

Berenice II became queen at an important juncture in Hellenistic history and was one of the defining figures of early Graeco-Egyptian queenship. She was trained in ancient weaponry and, at the tender age of 17, head of an insurrection in her home state Cyrene (modern Lybia). She ruled Egypt with her husband Ptolemy III (246-221 BCE) when the Ptolemaic kingdom was at the height of its power and took over the affairs of state when her husband left for war.

Berenice II is usually depicted as a heroic warrior queen in shining armor. But she was, at the same time, portrayed as a paragon of marital devotion, symbolized artistically by her Lock of Hair, which she once offered as a sacrifice and token for her husband’s safe return from war to her divine “mother,” Arsinoe-Aphrodite. Her offered lock of hair later became one of the canonical star constellations “Coma Berenices,” the only one named after a human being.

One of her earliest depictions is on a floor mosaic discovered in the eastern Nile Delta, where she is shown as the personification of Ptolemaic military and naval prowess with a tunic underneath a suit of armor, over which is a mantle fastened with a brooch over her right shoulder. She carries a shield on her back. Her face is full, her eyes bulging and wide- open, typical for the portraits of male rulers of her dynasty, like Alexander the Great. She is crowned with the prow of a ship, decorated with dolphins and marine serpents, herald’s staffs, and horns of plenty symbolizing the prosperity of her rule.

Mosaic with square emblem depicting Berenice II as personification of naval prowess (Thmouis, ca. 245-200 BCE; Greco-Roman Museum, Alexandria, inv. 21.739). Photograph by A. Pelle © Centre d’Études Alexandrines/CNRS, courtesy of Jean-Yves Empereur, Director.

Throughout the Renaissance she is also shown in keeping with her warrior queen assets and in the act of offering up her lock of hair, which stayed a beloved subject in visual arts as well as dramatic plays, and it remained so over centuries.

Antigone, the fictional heroine from the Athenian tragedy by Sophocles, is often portrayed in similar act of selfless dedication to family and cultural values – namely during her act of defiance in ritually burying her fallen brother against the orders of her king, claiming to rather uphold the values of an eternal and metaphysical plain than following worldly rules and damning her soul. She pays the ultimate price in the Greek tragedy and is interred alive. Forfeiting her life, she symbolizes the awe-inspiring tension of a doom willingly embraced and remains one of the pinnacles of heroic female imagery throughout the Renaissance and modernity. Until about a hundred years ago, both their depictions not only start to disappear, but there seems to be a shift when their imagery is evoked.

Antigone, the fictional heroine from the Athenian tragedy by Sophocles, is often portrayed in similar act of selfless dedication to family and cultural values – namely during her act of defiance in ritually burying her fallen brother against the orders of her king, claiming to rather uphold the values of an eternal and metaphysical plain than following worldly rules and damning her soul. She pays the ultimate price in the Greek tragedy and is interred alive. Forfeiting her life, she symbolizes the awe-inspiring tension of a doom willingly embraced and remains one of the pinnacles of heroic female imagery throughout the Renaissance and modernity. Until about a hundred years ago, both their depictions not only start to disappear, but there seems to be a shift when their imagery is evoked.

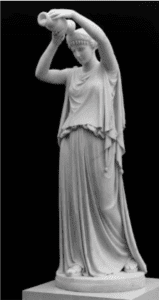

Antigone Pouring a Libation over the Corpse of Her Brother Polynices, Willian Henry Rinehart, 1870, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

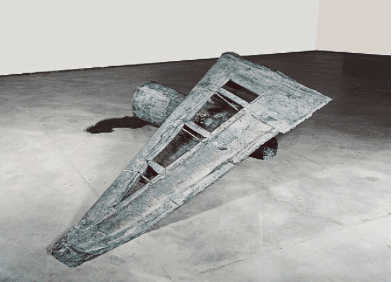

Not only are they strangely absent from our modern visual repertoire, but they seem to be reduced to an echo of their attributes. For example, in the latest work by Anselm Kiefer, done in 1989, Berenice has been replaced by an airplane wing and a lock of hair is the only remnant of a humane sacrifice amidst the horrors of war in this melancholy sculpture.

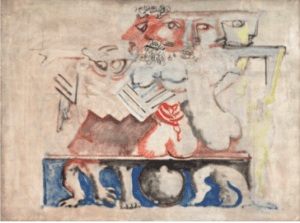

Mark Rothkos’ “Antigone” interpretation, done about 50 years prior as part of his surrealist-inspired myth paintings, renders the drama in the form of a multiple figure, at once Creon, Laios, and Oedipus – gazing into the past, the present, and the future – while Antigone is only evoked through the symbolism of the Sphinx, shown as the half-bird, half-hound creature slain by her father Oedipus. Again, our heroine is visually absent.

The heroism of these two women figures and their upholding of values and principles, their self-sacrifice in the name of family and in the face of tyranny has not only found resonance among artists from the Renaissance to modern art, but they also seem to be more than simple stand-ins for idolized femininity in the sense that they become a figuration of humanity in the face of despotism and cruelty, which makes the powerful rendering of their absence (as we see it in Anselm Kiefer’s work) all the more poignant by turning their lack of imagery into an appeal for their reemergence.

Mark Rothko “Antigone,” oil and charcoal on canvas, 34 x 45.75 in, National Gallery of Art

©Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.67477.html

If their vulnerability and femininity truly maps the extent of our humanity, then the absence thereof seems to be more emblematic than we would like to admit. Or as Mark Rothko put it:

“Those who think that the world of today is more gentle and graceful than the primeval and predatory passions from which … myths spring, are either not aware of reality or do not wish to see it in art.”

And although their imagery stems from a time when the arts had a religious and political significance they can no longer claim, we need contemporary artist to reimagine these heroines and introduce them into the visual repertoire of the 21st century.

© Anselm Kiefer

Anselm Kiefer, “Berenice” 1989, Lead, glass, photographs, and hair 3 feet 11 1/4 inches x 12 feet 9 9/16 inches x 10 feet 5 15/16 inches Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao