Jiha Moon always knew she was going to be an artist. She also knew there was a bigger world for her to discover outside of South Korea. At twenty-five, she became the only family member to travel to the United States, where she earned her second M.F.A. in studio art. Green cards were halted following 9/11, leaving Jiha without the ability to work. She poured herself into her studio, painting and experimenting constantly—a catalyst for a pivotal evolution in her work. Taking cues from East and West, Jiha Moon teases the viewer with cultural iconography traversing past and present day. She is a recipient of the prestigious Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors Grant and her work resides in major collections throughout the country.

Jiha, thank you for being with us today. What are your earliest childhood memories in South Korea?

My earliest recollection as a child was growing up in a happy family. My dad and mom were both big supporters of the Arts, and they were unconditionally and always supportive of our unique interests. I was unaware of my aptitude in art until I received an award in elementary school. The teacher asked my parents to attend the award ceremony, and it was from that one event that I learned I had talent. I also enjoyed receiving compliments, and this is how my love of art began. Soon afterwards, I started drawing and painting. I realized my brother was book smart and good at math. My sister was a dancer, cute and always entertaining my parents. I thought maybe I should be an artist; it came naturally and made other people happy. It was something I loved to do.

What is your first memory, or self-awareness, as an artist?

When I received the award in elementary school. I still cannot remember what I drew or painted. Ever since that time, I have made a concerted effort to pay attention to what I do. At the time, I really remember more “the feeling” of how I make art. Art brings me pleasure.

Yellowave, 2019, ink, acrylic, nail decals on Hanji, 36” x 41.5”. Currently on display at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, AR.

What did your father do?

He was a dentist.

And your mother?

My mom was a high school music teacher but did not work too long after marriage.

You are the middle child of three children. Are your brothers and sisters in the United States, or did they remain in South Korea?

Everybody is in South Korea except me. I’m the only one living in the States.

Tell me about your education.

I earned a degree from Korea University in South Korea, in studio art and art education. My mom encouraged me to protect myself financially which was the impetus to have an art education degree and a teacher certificate from Korea University. After that, I went to Ewha Women’s University. I wanted to pursue art a little bit deeper and received my first MFA degree at Ewha Women’s University in Korea. I was only 25 or 26, and I felt that there was a bigger world. I had to convince my parents to allow me to study abroad before I married or committed to something serious. They gave me a hard time to be honest, but eventually they supported me and honored my decision. I applied to graduate school in the United States and attended one semester in Baltimore, at the Maryland Institute College of Art, for a post-bachelor program. I wanted to go to a different school, one that offered more scholarship opportunities. So, I reapplied to graduate school, and I decided to attend the University of Iowa.

You are married and have a son?

Yes, I am married, and my son is 11 years old.

What is your husband’s profession?

He is a textile designer and an artist himself.

And where did you meet?

We met while attending the University of Iowa.

Were you homesick in the United States?

I was homesick when I was in Baltimore. After I moved to Iowa, I was in a group of 20 graduate students at the university, and they were strong artists, many of whom are still active artists and teachers. The group supported one another, and to this day, I really love the school because of that small community.

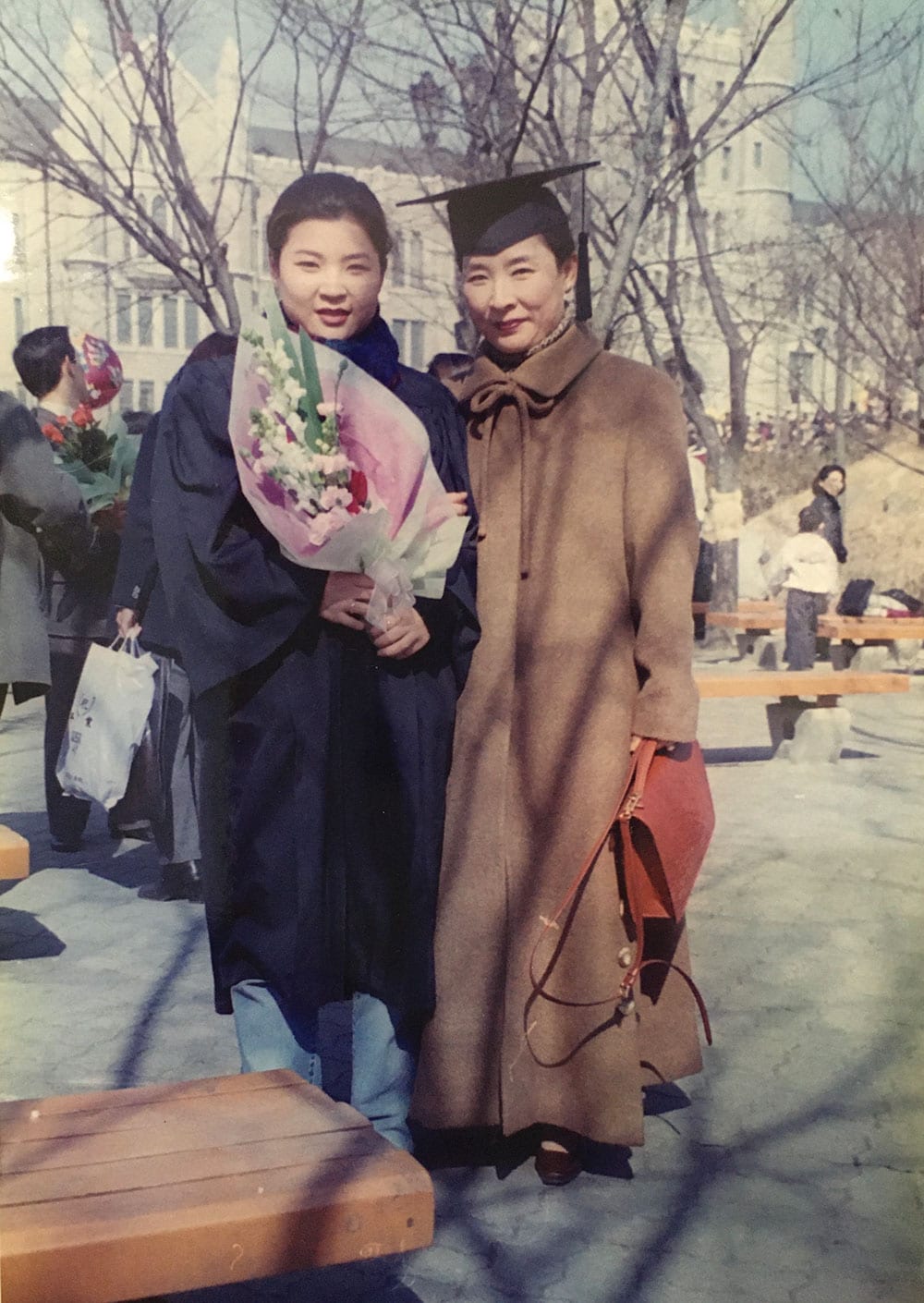

Jiha with her mother during her graduation from Korea University in 1996. Seoul, Korea.

You received two Masters of Fine Arts, including the one in Iowa. What was your focus?

My MFA degrees were in the same space; painting and drawing. Iowa supports building a community of students who want to teach in the future. Many students enter the teaching profession after their graduation. I was married during my junior year. But right after we were married, my husband received a job offer in Washington DC. He was a senior, and I was a year behind. Because I had one year left at school, he left for the job, and I stayed in Iowa to focus on my thesis and my studio classes. When September 11th happened, all immigration processes were halted, and I was unable to apply for a green card. I joined my husband in the Washington DC area after I graduated from the University of Iowa and finished my thesis. It was a difficult time for me because I could not work and did not have my green card or work permit. During this time, I painted constantly and switched my medium from oil on canvas to acrylic, watercolor and water-based medium. Work just was not feasible. I did not have a studio or window because we lived with roommates. The situation was hard, but it was the catalyst for exploration. I switched my medium, and I also started working with paper which has become my main medium now. Within this difficult period, I found my true medium, and I developed my work. Much of the work today stems from that difficult time. I found my identity, and the experience gave me a strong backbone. I really appreciate what happened at that time. It forced me to support myself and produce a large amount of artwork.

Does difficulty cause greatness?

Sometimes. I wish life was not so hard, and that it was just smooth sailing. Being an artist is not an easy task. Navigating choppy waters is critically important because no one knows when or how many times difficulty is going to come; or even where it is going to come.

How many years were “dark years” for you?

Two, maybe three years.

Did you feel that darkness?

Yes and no because it was my personal decision to take the path I chose. I had parents who provided an almost perfect opportunity, a different and easier path. But I chose my path, and I decided to move forward. I have a responsibility for my own decision making, so I cannot run to my mom and my dad and cry about what decision I made and ask them for help. Ultimately, it was my decision. Granted, they were always there to help me, listen to me and support me. But I knew that once I graduated, especially as an artist living in a different country, it came down to me.

How many hours a day did you work on your art during those dark times?

I worked all the time because that was also my escape. We lived with roommates, so I had to clean the house to do my share. Because I could not work, I applied to lots of group shows and attended art opportunities that were free for everyone. The rest of the time, I just made art.

Your earthenware and ceramic work have achieved acclaim in the recent years. What is the difference between these terms?

Ceramic work is a genre. Ceramic is also my medium. Earthenware is a type of clay body. Porcelain is white and a fine surface. Earthenware is a tough clay, not super fine as porcelain. I use different clay bodies because earthenware can be brown and can be a little bit beige color.

How did your ceramic work evolve?

Around 2012, I received an award from The Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia (MOCA GA). I wanted to invest in other fields, but I did not have financial support until I won this award. I went to a local clay studio and paid the one-year membership like you would for the gym with my grant money. I wanted to explore this new opportunity. I learned a lot going to that community studio. Painting is a very solitary experience. You make your work by yourself. You just talk to yourself and then engage with the work. But going to a ceramic studio, you interface with a lot of people, many of which are not fine artists. It was, for me, a social experience. I met all types of people, and it put me in a setting to interact with other people. It was an eye-opening experience. I learned my way and experienced a lot of things that I did not expect.

How do you juggle motherhood?

When I received the Artadia Award, I built an art studio in my home basement. Now, I am better able to focus my time. Going back and forth in Atlanta consumes many hours. My son is 11 years old now, but when he was much younger, I had to go pick him up, drop him off and then do my work. I was constantly fighting time. I wanted to prove I could do both. My goal has always been to have a happy family. It may not sound attractive to some people because in the art world there is prejudice about artists. To be successful, an artist has to be a certain way, devoted singularly to art for herself or himself. I had heard so many stories like these, and I wanted to go in an opposite direction. Anything in life is possible. Who says mothers as artists are not attractive and amazing? I wanted to do it my way. That was my biggest goal; to be an artist and a mother at the same time and balance both. To that end, my studio is set up in my home, which works perfectly because I also teach at Georgia State University. Being an educator and an artist are a big part of who I am. With COVID-19, I am teaching online courses from my bedroom where I have a computer. My husband and I were looking for a house that has that function. I will be 47 this June, and it has taken us this long to find a lifestyle that works for all of us.

Onceuponatime, 2019, earthenware, underglaze, glaze, 15” x 9.5” x 7.5”.

I want to talk about your art. Almost every art critic calls your work “mischievous.” Tell me about that.

I love a playful and mischievous quality in art. I grew up listening to parents say, “Don’t do this and don’t do that.” My son hears that from me as well, and he is one of the most mischievous people I have ever met on earth. He is very challenging. I want my artwork to be that way because it leaves you with a question. Probing someone to think about the other person’s perspective is a helpful quality in life. The biggest part of art is not the obvious but what is underlying that forces you to think.

What makes your work so nontraditional?

When people first meet, they have preconceived ideas about the other person based mostly on appearances. We all read people inaccurately based on appearance. Consequently, people are misunderstood. If I get to know you, who you really are, and know your whole history, then your truth reveals itself. I want my work to do that. I use a mix of cultural references, mixed-match color techniques to create confusion. Once someone engages with the art and tries to analyze the work, an understanding slowly occurs, like the process of getting to know somebody. My art is complex and confusing because misunderstanding is one step towards understanding. If you are misunderstood, somebody is interested enough to misunderstand, which is the first step towards understanding. I want my painting and my ceramic work to create interest, so it is revisited until it is understood. That is what I try to do.

You had an installation replicating a tea party, where you made use of your grandmother’s velvet, hand sewn pillows. Tell me about that.

I wanted to create an installation using all my ceramic pieces. The focus was not on the individual pieces so much, but to create an experience where the visitors would feel like they wanted to sit down and have tea. My pieces of art were commensurate with the theme; tea pots, dishes, little pieces or broken pots. I wanted to celebrate the tea party and created an Asian version of Alice in Wonderland. I wanted to have pillows because people use pillows in Asian culture instead of chairs. I used low tables instead of pedestal or western tables. The pillows were placed directly on the ground. I asked my grandmother if she could help, we have collaborated several times previously. My grandmother has piles of fabrics and scraps that she has collected for many years. My mother had nagged her for years to throw them away, but my grandmother loves fabric and thought someday it might go to good use. She was really happy to help me and also in use the old fabric she had saved all those years. She made all the pillows and sent them to me. I used the pillows, actually the pillowcases, in two different installations. My grandmother is 92 years old and is a big inspiration for me.

What is the story behind using Chinese fortune cookies as body parts?

The Chinese fortune cookie is an American invention. In Mainland China, nobody knows what a fortune cookie is. Asian Americans invented the fortune cookie, I think in San Francisco or on the West coast, and they became quite popular. For me, the Chinese fortune cookie is an American portrait because America is a big melting pot. All types of people come from all over the place to live in this country. There are so many rules we must follow to achieve our freedom. For me, that is a utopian view. The fortune cookie represents the American portrait because people constantly characterize it as a Chinese thing or Asian thing when in fact it represents America. I use the cookie in my ceramic work, sometimes as an eye or even an ear. It becomes part of the work and can be heavily camouflaged, decorated or extracted. People do not see it immediately unless they pay attention. When they recognize it is a fortune cookie, they re-engage, go back and look at it again. I use fortune cookies that way in my 3D work. I have used this iconography in my 2D work that I made into 3D work. The fortune cookie goes between genres, from my painting to my ceramics to my other mixed-media work. It has become my iconography.

ELYSIAN Publisher, Karen Floyd, with Jiha at MINT Gallery in Atlanta, GA, where they recorded Jiha’s Inspiring Woman interview. Both kept an appropriate distance from one another as recommended by COVID-19 safety guidelines.

Why is this paradox so integral to your art?

At first, I was upset when people saw me and assumed I was Chinese or Japanese. I wanted them to recognize me as a Korean. I realized that was not possible, and it was okay. Deep down, we are all human beings. The same is true for my husband when he visits my family in Korea with me. People have no idea if he is European, American or Canadian. To them, he is a foreigner in Korea, and I am a foreigner here. It is a narrow perspective, and for me, individualism is important. Everybody is their own, and they have their own universe. I wish we could stop categorizing.

How has COVID 19 impacted your community of artists?

It is a very difficult time because of our collective isolation, being trapped inside for everyone is hard. I think it is important to remember we are in this together and it will take I think a long time to be back to normal. Many museums, galleries and shared studio for artists are closed now and majority of their program went online format. Many staff got laid off from museums and artists are struggling. As part of the art community, I ask you to find a way to support them. Be a member of your local museums, and support artists and galleries if you can.

How long do you think?

Until the vaccine comes out hopefully within a year or two. No matter how long it takes, it is still a very long time. We’re already talking about what the options are at our school. By way of example, all my Fall classes might also go online. We are really living in a time of unprecedented uncertainty. I think this life style might be the new normal. It is sad to think about it, but we need to prepare for it. More importantly, we should not be afraid of it, but be cautious, so we can educate our younger generation in a positive way.

Can the uncertainty be a trigger for creativity or inspiration for artists?

While art can help as a therapeutic tool for many people, artists are struggling in this pandemic time. Many artists have lost their jobs and it is not a great market for selling art right now. It really is a mess. I keep wondering, how do we help each other? How do we support each other? I think that is very, very important for our future.

Where do you see yourself 10 years from now?

That’s a hard question. 10 years from now, I hope to be doing what I am doing right now as a mother, an educator and an artist. Those three roles are important, and they have to balance with each other for me to be a good human being.

Most everyone’s mad here, 2015, ink and acrylic on Hanji mounted on canvas, 28” x 44”. Jiha is represented by Mindy Solomon Gallery, Miami, FL, and Curator’s Office in Washington, D.C.

How difficult is that balance?

It is exceedingly difficult, but it is possible. I am not the only one doing it. There are so many strong women artists and educators who also have kids. I only have one child, but I know many women artists, I admire, who have more than one child.

What is the lesson to make that work?

Choose a good husband who will support your dream.

What piece of advice would you give the next generation of women?

I think I did okay because I was brave. I did not know too much and just jumped in. As I get older, I feel like I am getting a bit timid. I have lost an edge, and I miss that fearlessness. I was furious, and I was mad sometimes, but I was also brave. I did not hesitate. I saw the goal, and I felt like I had to have it. I worked my butt off, and I don’t regret what I’ve done. Also, I don’t regret all the bad experiences I had. Like I said, those experiences provided me a basis for who I am now. And one more thing . . . just enjoy your life. Do not be afraid.

You talk about bravery and fear. The older you get, the more fear you have?

Yes. I have to admit that, because with age, you know a little too much. I shake myself up. I am at a stage in my life that I should be braver and try to do new things, yet I have knowledge now that I did not have before. It is an internal conflict.

Pretend that I am one of your art students now. Give me a piece of advice as it relates to the world of art.

Do not be afraid. Just jump in. I see some students that have great ambition in the beginning of a semester, yet as time goes by, that ambition and drive lessen, and eventually, they give up. When you have a plan or ambition, when you have that energy level, just jump in, and get started. Do not overthink it. Sometimes, thinking too much ruins things.

Have you ever failed at anything?

Oh yes, many times. Hundreds of times. I still get rejections all the time, and it is a part of what I do.

And what is your piece of advice to a young artist that has experienced rejection?

Get used to it, and enjoy. You will move on to the next level soon. Do not be disappointed. This is what makes you better.