The Integrity of the Intimate

By C.S. Burke

Where are 49 worn wooden stairs that lead up from the gray metal door on Leonard Street in Lower Manhattan to Joanne Greenbaum’s third story loft, and she has climbed them multiple times a day, nearly every day, for the past 27 years. “Especially with the dog,” she says, nodding at Tino, her grizzled black-and-white Chihuahua, held fondly in the crook of her arm. The staircase runs diagonally the length and height of the building, with a landing at each of the four floors. A path of slow, steady, direct ascension, it ends at a rear window, high in the upper back corner, that provides the only light.

Joanne Greenbaum is no stranger to slow, steady ascents. She graduated from Bard College in 1975 and worked a nine-to-five career for decades in order to support herself as an artist. Even after she earned representation with the Rachel Uffner Gallery in New York and other galleries elsewhere, it was years before she finally decided to devote herself to painting, sculpting and drawing full-time. And it was still a move that carried some risk. The risk paid off, and Greenbaum can now set the terms of her work.

The years she spent developing her style outside the pressures of the limelight means she feels no pressure to change now that the limelight has come to her. She maintains a distance from the mainstream that enables her interactions with various mediums to remain intimate and her work to grow organically…

“I always wanted to do better earlier but that just never happened,” she says. “You want all these things to happen right away in your career, but it doesn’t always go that way. I’m one of these artists that was more of a slow burn. I never had a lot of attention, or money, at an early age. And maybe now I’m glad I didn’t.”

Inside, her studio is a dream of old New York: high, tin ceilings; nooked, hand-built bookshelves; a long communal table where she draws, sculpts, eats and hosts; three massive floor-to-ceiling windows, facing south. Paint-flecked ladders lean against a wall. Finished work is stored wherever it can fit, and fresh work—some complete, some unfinished—hangs on the walls. As we sit down to talk, she fiddles with a new sculpture before putting it aside. It’s made through a new process she’s experimenting with: molded wax, which is then cast in glass; the wax melts out during casting, leaving the glass form.

At the far end of the table are finished ceramic sculptures. Some are jagged and angular, almost architectural; others are flowing and feminine, suggesting a floral element. She pushes a book of drawings, done in pencil, across the table to me and demonstrates her technique: arm and wrist rigid, vibrating at the elbow, she lays down a series of forceful shadings on an imaginary piece of paper.

“I paint, I do sculpture, I draw constantly, so my activity is switching gears, all the time,” Joanne Greenbaum says. “I’ve maneuvered my life so that I don’t really have anything else to do. That’s the reward for years and years of having jobs and worrying.

“Now,” she says, gesturing to a large painting behind her, “each element of a painting, each color, is weeks apart. I like the fluidity of that type of working, figuring out what best suits my energy at any given moment. Each artwork is a world unto its own.”

Greenbaum is not a production-line type of artist. She uses no fabricationists. She loves to be in her studio, trying new materials, new paints and new approaches. She could be described as a loner but not an outsider. She maintains her relationship with the art world as she sees fit.

For instance, though her work was featured at Art Basel Miami 2018, she chose not to attend. “It’s not selfish,” she is quick to point out. “People who don’t understand think, ‘So everything is just about you.’ But that’s my dream. There is that thing of ‘fear of missing out,’ but there is also that new thing of ‘joy of missing out’–that’s more where I am. I don’t want to go the Miami art fair. I didn’t need to do that.”

I ask Joanne Greenbaum if she believes that artists—setting aside the commercial art world—are in it together, working toward a common goal of creating cultural expression. She quickly replies to the contrary. Her philosophy is that artists are independent, responsible for their individual choices alone.

In the largest sense, whether practical or philosophical, it seems many of the patterns of her life were set already when she was a child. “I was a quiet loner kid, and I liked to draw and paint. It was a place to retreat to. My mother never let me put artwork or school drawings on the walls—it didn’t occur to me until much later that that was kind of weird and mean, and I’m being kind. I think sometime in that room I decided to become an artist.”

Every decision she has made since has affirmed her commitment to making art. Over the years of what she refers to as her “doublelife,” there were several crossroads, including temptations to stick with the sure paycheck, the steady job or a personal relationship. In 2001, she earned a Guggenheim Fellowship, setting up her “nowor-never” moment. It led to what she calls “a juggling act”—years of making artwork, selling at a slow-but-steady rate and taking visiting artist or teaching jobs to supplement her income.

Her first gallery in New York was D’Amelio Terras, where she met Rachel Uffner. Uffner now shows Greenbaum’s work exclusively and will present a solo show in November 2019. Over time, Greenbaum’s pieces have risen in price, though there’s room for growth in terms of sales volume. “The art world seems to like old ladies,” she whispers, smiling coyly. “They like you when you’re really young or when you’re really old. That middle point is the hardest. There’s sexism there. There’s ageism there. When you’re [a woman] in your 40s, you’re anonymous; you’re invisible.”

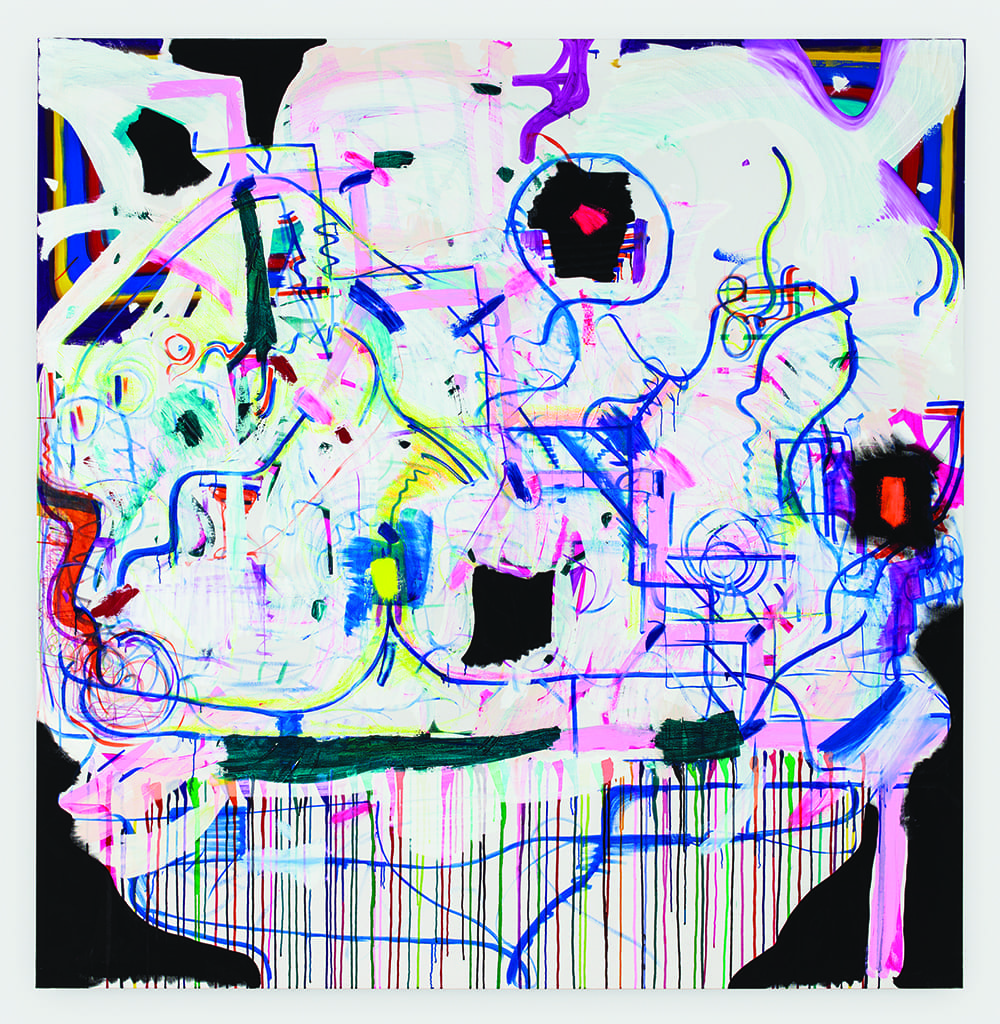

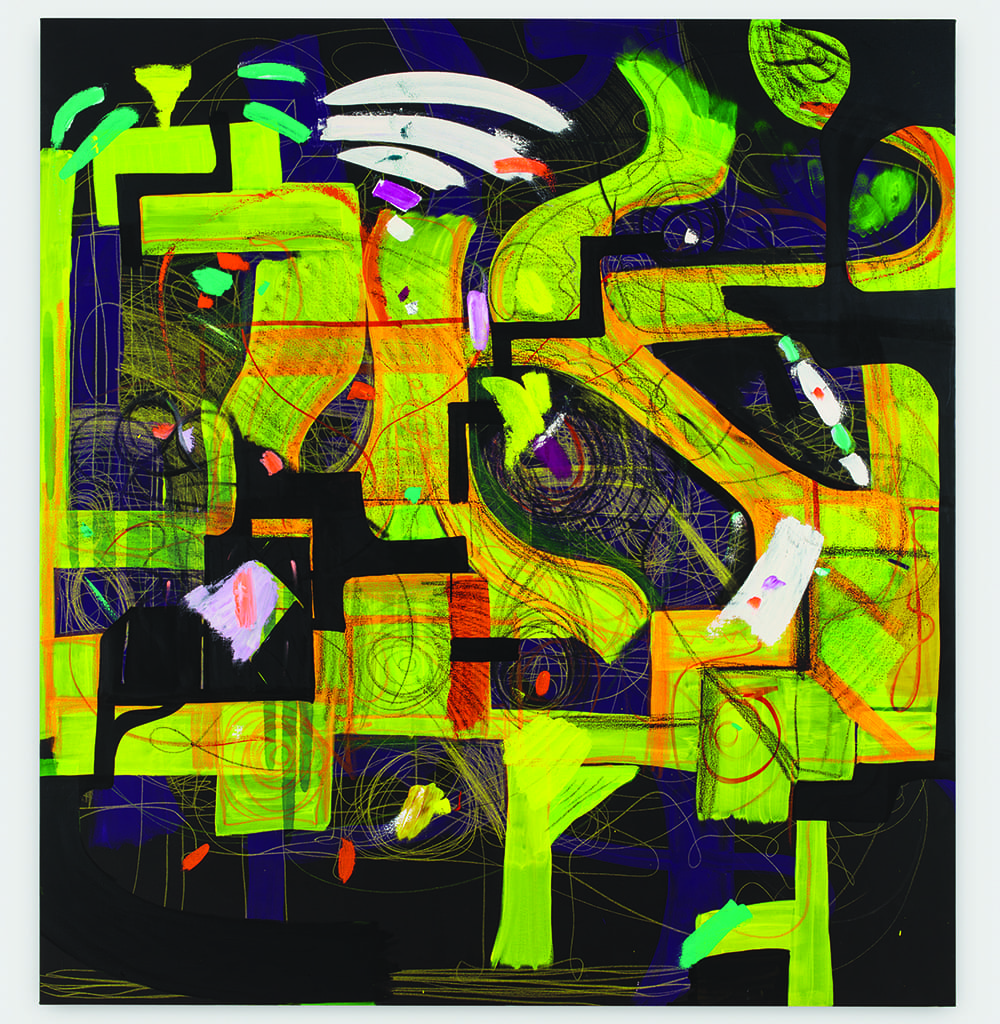

But, she is quick to add, invisibility has its benefits for an artist. If no one is watching, an artist can develop her work independently, away from trends and expectations. In Greenbaum’s case, the artwork reflects all of that: nothing looks like it was created with social media in mind, or evokes any specific engagement with specific trends, contemporary or passé. Nor does it project the naivety of the (often faux) outsider art aesthetic. It is not cynical, and it is not metaphorical. It is colorful and experimental but also, to some degree, almost classic. It could fit into a retrospective of twentieth century art as easily as it could twenty-first, which makes sense, because Joanne Greenbaum has bridged both worlds.

When I ask her if she thought the neglect of middle-aged artists who are women was the result of entrenched power structures (read: the maledominated art world) that fear the loss of economic control, or instead the result of bald misogyny, she is quick to respond: “Bald misogyny.”

Joanne Greenbaum believes that much of the contemporary artwork created by women is as good or better than what is being produced by their male counterparts. Of the work she sees in galleries, she said the pieces that speak to her most forcefully almost inevitably turn out to have been made by women. They remain undervalued not because of economics but exclusivity. “The men want to keep you out,” she says. “Men sell better because most collectors are male, and they are going to buy men. It’s changing a little bit, but it’s very slow. I’m at the point where people are buying my work but not that fast.”

She gestures again at the two huge finished paintings behind her, both Untitled, 2018.(Joanne Greenbaum does not title individual paintings. She says people read too much into titles, which, in any case, usually feel phony and forced.) “So I’ll just tell you,” she said. “This painting is $50,000, okay? A male friend of mine, a work of his the same size, is $250,000 dollars, you know? The market undervalues women. Women get paid less to the dollar across the board.”

Despite any frustrations she may feel with the art world, and the reception of her work, Greenbaum is positive, cognizant and thankful. “A lot of people don’t understand this—to be grateful for anything you get. I realize how rare it is in this world to be able to get up in the morning and do what I want to do. I’m angry all the time about the state of the world, but I don’t let it interfere with my work.”