“I am a woman above everything else.”

SHE WAS ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS women of the 20th century, arguably the most fashionable outside of Hollywood. A woman of supreme style, grace, calmness, and composure, she was America’s original princess. And yet, she wore a mask, always struggling to shield herself from a peering world, wrapping herself in privacy like a cloak on a frigid winter’s day, and endure the relentless limelight that shone upon her throughout her entire life. Her premature death at the age of 64 elevated her to the status of legend. Reams have been written about her. Countless photographs have been taken and miles of film. But the one thing she coveted more than anything was privacy—and it was the one thing that Jackie, who had all the money in the world, could not buy.

THE EVENTS OF HER LIFE are well-chronicled. Jacqueline Lee Bouvier was born in Southampton, New York, the summer playground of “old money” families, on July 28, three months before the Stock Market Crash of 1929. Her father was a handsome, debonair Wall Street stockbroker named John “Black Jack” Vernou Bouvier III, and her mother was American socialite and amateur equestrian champion Janet Norton Lee Auchincloss. Janet came from a life of privilege. Her father was the enormously wealthy lawyer, real estate broker and banker, James Thomas Aloysius Lee, himself the son of a successful attorney.

Jack and Janet’s marriage was volatile from the start. Jack Bouvier was a notorious womanizer with a deep affection for the bottle, and Janet, despite one failed attempt at reconciliation, had zero tolerance for her philandering husband. From the moment of Jackie’s birth, she was caught in a relentless tug-of-war between her parents for their child’s affections. Jackie adored her father. Her father adored Jackie. Daughter favored father with the same wide-set eyes, straight nose and full lips. Her little sister and only sibling, Caroline Lee (“Lee”) Bouvier (1933-2019), favored her mother. Jack did not feel the same sort of love for his younger daughter as he did his elder.

Upon the engagement announcement to Senator John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Bouvier would quickly go from the girl behind the lens to the center of media attention. MEDIAPUNCH INC / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Jackie was 11, and Lee was seven when their parents divorced, and they left with their mother. Two years later, Janet married the second of her three husbands, Hugh Dudley Auchincloss, Jr., a stupendously successful stockbroker, lawyer and Standard Oil heir who came from a storied family of merchants, financiers and Republican politicians. They summered in Newport, Rhode Island, and spent the rest of the year at the Auchincloss estate, Merrywood, in McLean, Virginia. Jackie proved a hardworking and conscientious student at boarding school, followed by two years of college at Vassar, a Smith College program in her junior year at the Sorbonne in Paris and, lastly, at George Washington University. She entered Vogue magazine’s “Prix de Paris” essay competition and out of 1,279 entries, won. The grand prize was a job at Condé Nast, Vogue’s New York headquarters, and a six-month fashion apprenticeship in Paris, but she determined after only one day on the job that sitting behind a desk was not for her. So, she forfeited the prize and embarked upon a grand tour of Europe with her sister, Lee, instead.

Whether she ever made her own bed, went shopping for a gallon of milk or hemmed her own skirt, we’ll never know—but if she did, she didn’t have to. But I needed to find the one constant in the life of this incredible woman that made her life so incredible. That’s what I wanted to know, but before I could find out, I had to look deeper than I ever had before into the life of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis.

I FOUND THAT THREAD early on in my research. When Jackie was 22, she moved back home to Merrywood to live with her stepfather and mother after getting a part-time job at the Washington Times-Herald as a receptionist. Finding herself again behind a desk, she lobbied for something more exciting and a week later became the newspaper’s “Inquiring Camera Girl,” with the assignment of photographing random pictures of “the man on the street” and writing witty captions to go with them.

She loved to write, she loved to read and she loved books. That was the thread.

During this time, she became engaged to a stockbroker named John Husted, Jr. He was her very “first love,” but after three months, she found him to be “immature and boring” and broke off the engagement. Curiously, it was during her engagement that she met the young, magnetic junior U.S. representative from Massachusetts, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, nicknamed “Jack,” at a dinner party. She found him charming; he found her fascinating. He was chatty and witty; she knew how to listen, flatter a man and laugh. He came from a wealthy, “new money” family; she came from a wealthy, “old money” one. They both were Catholic and of Irish descent. He was a Democrat, and she was a Republican, but that didn’t matter. What mattered was they had everything going for them and made an absolutely stunning couple.

Seven months later, Jackie was in London covering the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II for the paper when Jack phoned and asked her to marry him. She accepted.

She harbored concerns over the behavior her new fiancé had in common with her philanderer father. Jack’s insatiable sexual appetites, according to all accounts, never abated, and throughout his engagement and marriage, countless women were lured into his bed, the most famous being Marilyn Monroe. In her tapes, Jackie said, “I thought I could conquer him.” She thought wrong.

Nonetheless, their engagement was announced June 25, 1953. They married at St. Mary’s Catholic Church on Spring Street in Newport, Rhode Island, on September 12. Seven hundred squeezed into the church, and the reception for 1,200 was held at the Auchincloss family’s summer home in Newport, Hammersmith Farm, where Jackie was in charge of taking care of the chickens when she was growing up. After Kennedy took office as president, Hammersmith Farm would be known as “the Summer White House.”

The new bride was completely in love. “I remember thinking, ‘I won’t have to be afraid when I go to bed or wake up,’” she said years later in her taped interviews when she recalled the early days of her marriage. That level of love came to Jack gradually and over time. He was a complex person, and the marriage was as much a clever and calculated plan orchestrated by his father, Joe Kennedy, as by his own desires. Joe had groomed Jack, his second son, from the moment his eldest, Joe, Jr., was killed in World War II. It has been said that, as far as Joe Kennedy, Sr. was concerned, Jackie had everything he could wish for in a political helpmate for his son.

John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Lee Bouvier were married on September 12, 1953. The wedding dress was created by designer Ann Lowe. Opposite: Jackie throwing the bouquet. PHOTOGRAPHS BY TONI FRISSELL / COURTESY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LOC.GO

SHORTLY AFTER THEIR MARRIAGE, Jack was diagnosed with Addison’s disease, a chronic and debilitating adrenal deficiency. He underwent spinal surgery meant to relieve the horrible pain from the back injury he sustained in World War II, but the operation nearly killed him, and in one of three times in his life, he was given last rites. Jack was bedridden for a half a year, and Jackie tended to him every waking minute. Within their first three years of marriage, Jackie suffered a miscarriage and, on August 23, 1956, delivered a stillborn daughter. On August 3, 1957, Jack Bouvier died from liver cancer. On November 27, 1957, Jackie finally gave birth to a healthy daughter filled with the promise of a wonderful life.

Throughout, the one constant in their lives was politics. “I was always a liability to him,” Jackie reminisced in her tape recordings, “and I told him, ‘I’m so sorry for you that I am such a dud.’” But America and the world proved her wrong. Over the next five years, the Kennedys traveled together as much as possible on his campaign trips, and soon JFK’s campaign manager realized the crowds were twice as big whenever Jackie was with him. In November 1958, JFK was elected to a second term in Congress, and he realized the success of his re-election campaign could largely be attributed to his wife. Jackie was, he said, “simply invaluable”— and not just in public. At home, she supervised his wardrobe, his meals, his leisure time and their social agenda, and he came to depend upon her for—as Arthur M. Schlesinger would write in 1959, after first meeting Jackie at the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port—her “tremendous awareness, an all-seeing eye and a ruthless judgment.”

On January 3, 1960, everything played out the way things had been carefully planned, and Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts formally announced his candidacy for President of the United States of America.

NOW JACKIE WAS PREGNANT once again, and rather than run the risk of losing another baby, she remained home in Georgetown and supported her husband in other ways, most notably a syndicated newspaper column she wrote called “Campaign Wife.” Admired from the moment she was presented in 1947, at the age of 17, as Debutante of the Year for her tremendous style (“Always dress like a marble column,” she was later quoted as saying), people were captivated by her poise, warmth and breathy voice. As a speaker, she was naturally composed and compelling, yet she spoke with that aristocratic “twang” that had her pronounce her o’s like aw and single syllable words, like year, stretched to two, as in ye-ah. People loved that about America’s princess; it made her sound so regal.

There were, however, concerns from JFK’s primary campaign headquarters. He was heading to campaign in West Virginia, one of the poorest states in the nation, when Jack’s advisors warned him that Jackie’s superior ways would harm his chances in a state he was already predicted to lose. Instead, crowds lined the streets ten deep in an attempt to capture even a glimpse of this lovely young woman. Her warm smile, her affected but charming accent and her sense of calm and composure captured the hearts of West Virginia, and Jack took the state handily. Now the challenge was whether he could win the election. The nation was in the throes of reinventing itself after four decades of world wars bridged by the Great Depression and now, at the height of the Cold War with Russia. Once again, Jackie was the answer.

On November 8, 1960, by one of the narrowest margins of any presidential election, JFK defeated Richard Nixon to become the 35th president of the United States, the country’s first Catholic president and the youngest president in American history. Two weeks later, on November 25, Jackie gave birth to their first son, John F. Kennedy, Jr., and in the ensuing two weeks of her hospital recovery, reports were issued daily to assure a delighted nation that all was well with mother and child. On January 20, 1961, with eight inches of snow having fallen the night before, JFK was sworn into office on the steps of the Capitol Building. Jackie, incredibly slim after the recent birth, was dressed in an impeccably tailored inauguration ensemble designed by her friend, Oleg Cassini, wearing for the first time the “pillbox hat” that would become one of her most recognized fashion statements. Looking at the film footage, Jackie seems forgotten as seven or eight people separate her from her husband after the inauguration ceremony, as the guests filed out. But when she eventually caught up with him for a seemingly private moment, their feelings were captured in a photograph that would become one of her favorites. There were, she said in her tapes, tears in his eyes.

President and Jacqueline Kennedy sailing with her parents, Janet and Hugh Auchincloss. Jackie Kennedy is smoking and reading with the President. The group is aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Yacht Manitou, in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. Sept. 14, 1962. EVERETT COLLECTION HISTORICAL / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AS THE WIFE OF THE PRESIDENT of the United States, Jackie not only had become a cultural symbol but a symbol of the ideal woman. With her refined looks and trim figure, she idealized the best in American womanhood, and though she looked like no one else, every woman wanted to look just like her. She favored Chanel, Balenciaga and Givenchy. Her husband’s salary as president was $100,000 a year. She spent $150,000 that first year in the White House on her clothing alone. After all, she had an image to keep up.

The world was fascinated with Jackie. Aware she was public property, she discreetly and skillfully kept the press at arm’s length while wearing kid gloves. She hired her own press secretary, the first to do so, as a cushion between herself and the media. Her name was Pamela Turnure, a young and attractive woman whose father was a New York banker, and whose stepfather was the editor of Harper’s Bazaar. She was, by all accounts, yet another one of JFK’s conquests. Nonetheless, she and Jackie remained friends.

In an interview, Jackie was asked what her role was as the wife of the president. “I think the major role of the first lady is to take care of the president so that he can best serve the people. And not to fail her family, her husband and children,” she replied. This wonderful woman, who had written in her high school yearbook that her ambition was to not become a housewife, managed seamlessly with the help of a large staff, leaving her time not only to fulfill her obligations as first lady, but to devote herself to her lifelong obsession with the fine and performing arts. To this end, she established the National Endowment for the Arts and laid the foundation for the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Perhaps Jackie’s greatest accomplishment was the restoration of the sorely neglected White House, which had last been given any serious attention in 1809 by Dolly Madison, wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States. Jackie took great care in returning the mansion at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to its historical character, gathering a team of experts in their respective fields. Among them was Adrianna Scalamandre Bitter of Scalamandre Silks, who undertook the supervision and manufacture of the restoration textiles; American furniture expert Henry du Pont; Rachel Lambert Mellon, who redesigned the White House gardens; and key to them all, one of the great interior designers of her day, Sister Parish. Jackie set out to transform “the house of the American people” into a showplace. She solicited contributions from donors, initiated a treasure hunt for lost White House furnishings and advocated a Congressional bill that established all White House furnishings as the property of the Smithsonian, rather than the property of departing presidents and their wives. She founded the White House Historical Association, the Committee for the Preservation of the White House and for the first time in the stately home’s history established the permanent position of curator of the White House, the first of whom she herself personally interviewed and hired. For the perpetuity of the historic building, she established the White House Endowment Trust and the White House Acquisition Trust. On February 14, 1962, Jackie invited the nation on a televised tour of the completed public rooms in a CBS News special program, “A Tour of the White House.” More than 56 million tuned in to watch the special, which subsequently was televised in 106 countries. Jackie Kennedy was the only first lady to win an Emmy Award, in 1962, which was accepted on her behalf by Lady Bird Johnson.

Jackie’s itinerary of official state visits abroad once again raised fears that her regal appearance and soft-spoken voice would not appeal to Europeans. Yet again, all fears were quickly dismissed. Jackie spoke four languages fluently, and she charmed everyone she met, most notably the stern, formidable President Charles de Gaulle of France. He was immediately charmed by her flawless French and intelligent conversation, and although President Kennedy’s political mission failed, the success of the visit could not have been greater. As her husband announced upon their return home, “I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris—and I have enjoyed it.” Indeed, a dependency and love evolved between Jack and Jackie, and although his extramarital affairs continued, Jackie appeared to ignore them, which drew Jack even closer to her.

Jackie once again gave the nation something to look forward to celebrating with the announcement that she was again expecting a baby. However, on August 7, 1963, five weeks shy of her due date, she gave birth to Patrick Bouvier Kennedy by emergency Caesarean section. His little lungs were not fully developed, and two days later, the infant died. The loss of three of the five children Jackie had carried affected her terribly, and she sank into a deep state of depression. On the insistence of her sister and with the reluctant consent of Jack, Jackie accompanied Lee on Lee’s boyfriend’s yacht in the Mediterranean to recuperate far away from the public eye. When she finally returned, on October 17, 1963, she admitted that while she had been away too long, she needed to deal with the “melancholy after the death of my baby.” Little could she know that she only had five weeks left to spend with her husband.

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy (center) and her sister, Princess Lee Radziwill of Poland (right), visit with camel driver Bashir Ahmad (left) and his family at the residence of President Mohammad Ayub Khan in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. CECIL STOUGHTON. WHITE HOUSE PHOTOGRAPHS. JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM, BOSTON

THE REST, AS THEY SAY, IS HISTORY. I remember, and maybe you do too. It was November 22, 1963. I was 10 years old and in the fourth grade when the principal’s voice was unexpectedly heard on the school intercom. It was an hour before the end of the school day. His voice sounded strange. He said, “President Kennedy has been shot in Dallas, Texas. Go home. The buses are waiting. If you are a walker, go home immediately.” I went to the first-grade classroom to get my sister, Cindy, and we walked the three-quarters of a mile home, as we sometimes did, instead of taking the bus. We didn’t understand; we were too young. We just knew something bad had happened. But we knew about Mrs. Kennedy. Mom adored her, bought every magazine at the grocery store that had her picture on the cover, dressed like her, wore her hair like her, even bought a pillbox hat. “She was a lady,” Mom said. Mom was a lady. “And I’m raising you two to be ladies,” Mom often scolded.

We got home to find she had not returned from grocery shopping. Thanksgiving was the following Thursday, and she always prepared well in advance of things. In those days, Dad, a consulting HVAC engineer, had his office in an enclosed porch adjacent to the living room, and that’s where we found him, sitting in front of our 12-inch black and white television, his head buried in his hands, weeping uncontrollably along with the rest of the world.

“From Dallas, Texas,” Walter Cronkite had announced on the television, “the flash apparently official, President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time, 2 o’clock Eastern Time, some 38 minutes ago.” The brief pause as he put his glasses back on showed an expression on his face that everyone felt, like their heart had been torn out of their chest. Jackie would reflect on her own grief: “Do you think that God would separate me from my husband if I killed myself? I feel as though I am going out of my mind at times. Wouldn’t God understand that I just want to be with him?”

Jack and Jackie Kennedy had been married only 10 years, in which time they had five children, of whom only two survived. Together, they wove a mantel of calm and peace during a terrifying time in United States history that included the Cuban Missile Crisis.

President John F. Kennedy (right) and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy (holding bouquet of yellow roses) arrive at Houston International Airport in Houston, Texas; Air Force One is visible in the background. CECIL STOUGHTON. WHITE HOUSE PHOTOGRAPHS. JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM, BOSTON

The Kennedy years, like Camelot, disappeared into the mist of history, a time that had never been known before and most likely will never be seen again. Jackie said, “There will be great presidents again, but there will never be another Camelot.” The title song of the Lerner and Loewe Broadway musical, Camelot, was her and Jack’s favorite, and these words have forever been associated with the Kennedy administration:

Don’t let it be forgot

That once there was a spot

For one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot.

But for me, at least, the words that come in the stanza before are far more compelling:

Ask ev’ry person if he’s heard the story, And tell it strong and clear if he has not, That

once there was a fleeting wisp of glory Called Camelot.

Camelot! Camelot!

Now say it out with pride and joy!

Camelot took place during medieval times. Interestingly, Jackie once said, “Our culture will become like it was during the medieval times when there truly was a cultural elite. The rest of the people will just watch television, which will be their only frame of reference.” Sadly, she was ever so right.

“DURING THOSE FOUR ENDLESS DAYS in 1963, she held us together as a family and a country,” Jackie’s brother-in-law and Jack’s youngest brother, Senator Edward Kennedy, would later say in his eulogy at Jackie’s funeral on May 19, 1994. “In large part because of her, we could grieve and then go on.” Though no longer first lady, and despite her attempts to maintain a low profile and give her children as normal an upbringing as she could, Jackie appeared even more frequently in the tabloids. She raised her fatherless children in as normal an environment as she, a single mother, could give them. Shortly after her husband’s assassination, they moved to New York City and bought a 15-room apartment on Fifth Avenue, nor far from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Still, tragedy would not leave the family alone. Five years later, on June 5, 1968, her beloved brother-in-law, Bobby Kennedy, also died by an assassin’s bullet. The following October, she married her sister’s former boyfriend—the man whose yacht she had gone on to recuperate after the loss of her baby Patrick. His name was Aristotle Onassis, a Greek shipping magnate who was considered the wealthiest man in the world.

Now, she was “Jackie O.” Like a nomad, she would go from one of their six residences to another—her Fifth Avenue apartment; her horse farm in New Jersey; his Avenue Foch apartment in Paris and private island, Scorpios, off the coast of Greece; his mansion in Athens; and his yacht, Christina O. Increasingly, they were more apart than together, and their marriage showed signs of strain, playing out like acts in a Greek tragedy. There was Onassis’ spurned mistress, the great opera diva Maria Callas, who seemed to always be waiting in the wings and to whom Onassis remained devoted. There were rumors of constant rifts over Jackie’s excessive spending of her husband’s money—never of her own, which she squirreled safely away. Then, on January 23, 1973, Onassis’ only son, Alexander, died from injuries sustained in a plane crash the day before. He was only 24.

“My father loved names, and Jackie loved money,” Alexander had said of his father’s new wife, with whom both he and his sister had had a tense relationship. It was too much for Aristotle to bear. Alexander was handsome, bright, showed so much promise and was the heir apparent to his proud father’s empire; now he was gone. Less than two years later, consumed by a grief he never overcame, his health steadily and sharply declining, Aristotle Onassis died on March 15, 1975, from respiratory failure, a complication from myasthenia gravis, a debilitating neuromuscular disease. He was 69. Jackie was left with a fortune—reports vary from $10 million to $26 million, which, along with her Kennedy money, burgeoned to several hundred millions by the time of her death under the financial stewardship of her last companion, Maurice Tempelsman, a Belgium-American diamond merchant. Jackie lost her only surviving stepchild in November 1988, when Onassis’ only daughter, Christina, died of a heart attack. She was 37.

Still, the thread that tied her life together—reading, writing and books—remained taut, and in 1977, she took a job at Viking Press as an editor and then moved to Doubleday & Company as an associate editor. It is little known that Jackie edited more than 100 books during a career that spanned 20 years, longer than both her marriages combined. It was during this time that she also immersed herself in the rescue of Grand Central Terminal, one of the last great buildings in New York City, and its renovation, a serious addition to her already extensive legacy. In November 1993, the lifelong equestrian was thrown from her horse during a foxhunt in Middleburg, Virginia. She was taken to the hospital, and during the examination, a swollen lymph node in her groin was discovered. Believed to be an infection, she was misdiagnosed. Jackie was, in fact, in the early stages of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a painful form of cancer that attacks the autoimmune system. Two months later, she underwent chemotherapy, but by March, the cancer had metastasized to her spinal cord and brain, and by May, her liver. On May 18, she returned home from New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, and the following evening, May 19, 1994, she died peacefully in her Manhattan apartment, surrounded by her children and the people she held most dear. Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis was dead at age 64.

Her son, John, Jr., stood outside his mother’s Manhattan apartment building the following morning and said, “My mother was surrounded by her friends and her family and her books, and the people and the things that she loved. She did it in her very own way, and in her own terms, and we all feel lucky for that.” Four days later, on May 23, her funeral mass was conducted at the church she had attended since she was baptized in 1929 and later confirmed as a teenager, the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola.

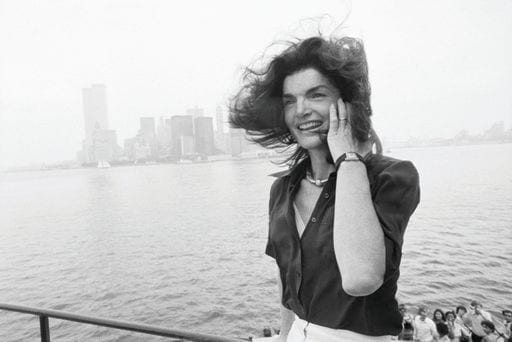

Her body was interred alongside her husband, John F. Kennedy, and their children, son Patrick and daughter Arabella, at Arlington National Cemetery. The familiar towers of lower Manhattan and the not-unknown physiognomy of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis can be made out in New York Harbor as she returns to the Big Apple from Staten Island, where she toured the Snug Harbor Cultural Center. Cemetery. She was survived by her daughter Caroline and her husband, Edwin Schlossberg, their three children; her sister, Lee Radziwill; and son John, Jr. Five years later, John, Jr. and his new wife, Carolyn, perished in an airplane crash over Nantucket. John had been piloting the small aircraft. The first child ever born to a president-elect was dead at 38, and with him, the last flicker of hope that was Camelot was extinguished forevermore.

The familiar towers of lower Manhattan and the not-unknown physiognomy of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis can be made out in New York Harbor as she returns to the Big Apple from Staten Island, where she toured the Snug Harbor Cultural Center. BETTMANN / CONTRIBUTOR / GETTYIMAGES.COM

In 1996, children Caroline and John auctioned many of their mother’s possessions at Sotheby’s auction house in New York. It was the auction of the century, and the demand just to preview the auction was so intense that people had to draw from a lottery to get admission. Sotheby’s projected the auction would realize $4.6 million. Instead, it went eight times over the estimate—almost $35 million. Silly of Sotheby’s — after all, how could you put a price on Camelot?

So, what lessons can you learn from Jackie? Grace under pressure. Dignity in adversity. Absolute devotion to family. Charm. Kindness. Dress for others but more importantly, for yourself. Pursue your interests. Grow yourself. Be the person you are meant to be. Let’s leave her with the final word:

“I have been through a lot and have suffered a great deal. But I have had lots of happy moments, as well. Every moment one lives is different from the other. The good, the bad, hardship, the joy, the tragedy, love, and happiness are all interwoven into one single, indescribable whole that is called life. You cannot separate the good from the bad. And perhaps there is no need to do so, either.”