Marion Mahony Griffin

The Matriarch of American Architecture Who Invented Organization

“It’s difficult to separate the architect and artist from either of her work husbands: Mahony Griffin’s metaphorical one (Wright) and her literal one (Walter Burley Griffin). In fact, attempting to do so creates a Marion Mahony Griffin that didn’t exist. While Mahony Griffin nursed a grudge against Wright for a large part of her life, their contributions to the Prairie School are intertwined—they each helped make the other’s career. Meanwhile, Mahony Griffin was such a fierce cheerleader of her husband, the Prairie architect Walter Burley Griffin, that she happily painted herself in his background.”

—CLAIRE ZULKEY,

Frank Lloyd Wright’s best frenemy, 2017

The Prairie Movement, or School, is America’s first indigenous form of architecture. It was inspired by the wide, flat treeless expanses of America’s native prairie landscape and derives from, and is in harmony with, the Arts and Crafts Movement launched in the United Kingdom by William Morris and his associates, becoming an international trend in the decorative and fine arts and spawning the Modern Style, later known as Art Nouveau.

Okay. Here’s what you need to know. Not until the early 1900s—and even then, only among forward-thinking, like-minded people—did the concept of, “A place for everything, and everything in its place”, become important. In short, it was the birth of organization. Throughout Victorian and Edwardian times, every square inch of space in the home was cluttered with baubles, tchotchkes, gewgaws, and trinkets. Today we call these people hoarders. In those olden days, it was considered the height of home fashion and interior design and was how people showed off their wealth. Molly Brown, who struck gold, became the wealthiest woman in the Rockies, and survived the Titanic, draped her doorways with feather boas and stuck potted palm trees in every corner of every room.

How, and why, organization came into being and radically changed architecture can be credited to one woman—a woman whose name you probably are not familiar with but, once you read her story, you’ll never forget. For all intent and purposes, she was the inventor of organization. She created the principles of “sustainable, organic architecture,” streamlined space, and gave practical purpose to space and how to use it. For example…

A long bench up against a wall served as seating and underneath, sliding panels allowed for storage, dismissing the need for cabinets, closets, and bookcases.

One chair design, and only one, was used in a room. Put four or five side-by-side along a wall facing that long bench and you have seating for 8 or 10, and a wide aisle in between.

Windows, designed to bring in light, were patterned with stained glass, serving two purposes: the art was in the stained glass and therefore, no artwork was necessary, or even desirable, on the walls, which were painted in one dark, natural color with a textural effect. Bring the eye up with a light-filtered ceiling of stained glass. Put one vase out with some flowers tossed in like they don’t care and the room is complete. No clutter. Simple. Practical. Brilliant. And organized.

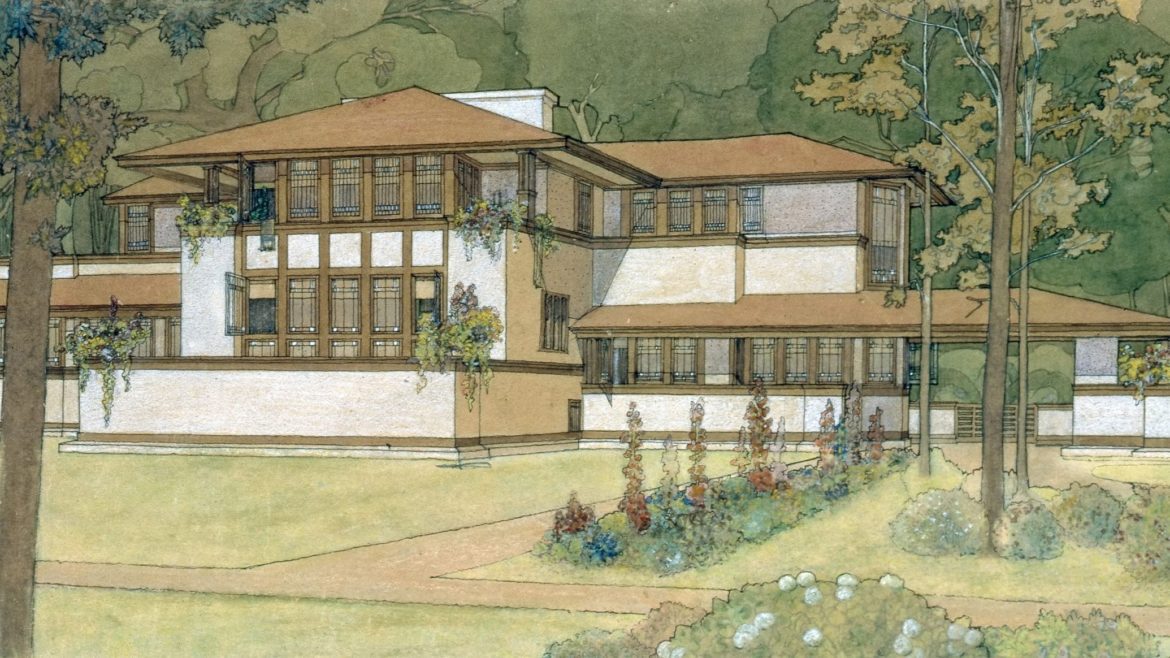

A room credited to Frank Lloyd Wright but executed with Marion Mahony Griffin

Here is her story…

“Behind every great man,” as the saying goes, “is a woman.” This is true of American architect and artist Marion Mahony Griffin who, 60 years after her death, is universally acclaimed as “the real architect behind Frank Lloyd Wright,” the trail-blazing force behind 20th century American architecture. It was Marion who “did the drawings people think of when they think of Frank Lloyd Wright.” Her watercolor renderings defined Wright and yet it was Marion who was the key influence behind the development of the Prairie Style for which Wright (1867-1959) would garner international renown. And what’s more, “as was typical for Wright at the time, he credited her for neither.”

Marion Mahony Griffin

Marion was born in Chicago in February 1871 to Jeremiah Mahony, an Irish journalist and teacher from County Cork and Clara Perkins, a prominent school principal.

Marion’s dramatic childhood was the early impetus that would drive her extraordinary life. She was only nine-months-old when the family crossed the Randolph Street bridge and fled for safety from the Great Chicago Fire, which destroyed 3.3 square miles of downtown, 17,450 buildings, and left 100,000 homeless. The family moved to the then-rural Winnetka area on Chicago’s North Shore, where memories of towering, ancient trees and winding shores stayed with her to influence her signature style of architecture.

Clara, Marion’s mother, was her lifelong role model. After her husband’s premature death in 1882, Clara joined the powerful Chicago Women’s Club, a progressive circle of women’s rights activists. Growing up, her own family, the Perkins, were very political and often held social gatherings at their home to discuss important matters of the day. One frequent visitor was their friend, Abraham Lincoln.

Growing up during the Great Rebuilding of Chicago gave young Marion a priceless, firsthand perspective as the most radical change in architecture experienced in the history of our country rapidly unfolded. Building a razed city from parched ground, architects forfeited fancy ornamentation for a cost-efficient, streamlined style girded by steel rather than iron. This robust change in materials allowed for larger windows that flooded the interior space with natural light, and taller, stronger structures that became known as “skyscrapers.” The Chicago School, as it was called, was the school of architecture that Marion would choose to associate herself with, rather than the Prairie School, where she publicly made her mark as an architect.

Financed by the wealthy and influential society progressive Mary Hawes Wilmarth, Marion studied architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and, in 1894, became the second woman to graduate from this preeminent research university in modern technology and science. After MIT, she traveled extensively throughout Europe and on her return later that year was hired as a drafter by her cousin, architect Dwight Perkins, who shared the loft space in downtown Chicago in Steinway Hall with a young architect who had just left the firm of Adler & Sullivan to start his own business. His name was Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1895, Marion became his first employee. It was the beginning of a tumultuous professional and personal relationship that would last the rest of their lives. “You have to give it to Wright,” architecture professor Paul Kruty explained of the social stigma of women working at a profession in those days, “that he thought hiring a woman was fine.” This unorthodox move resulted in Marion becoming the first woman in Illinois to obtain a license to practice architecture.

His Girl Friday

Marion proved herself to be a “team player” who, in keeping with society’s male-subordinate role of women, showed a deferential side working in the shadow of Wright and later, her husband, architect Walter Burley Griffin. Witty and effervescent, she was readily identified by her loud laughter. “She walked into the room, and everything stopped,” explained David Van Zanten, an art historian at Northwestern University. Years later, Barry Byrne, a colleague of Wright’s, remembered Marion as “a good actress, talkative, and when around Wright there was a real sparkle.” When the two were together, “it always promised to be an amusing day.”

In this atmosphere, for 15 years, the magnetic collaboration between Marion and Wright opened that chapter in architecture that can only be identified as purely, completely American. In hindsight, however, the credit among scholars is solely attributed to Marion. “When she invented that style, she put the buildings in a whole new way that hadn’t existed before. Everybody copied it—it became the way of presenting architecture in America,” Paul Kruty states.

Their collaboration ended in 1909, when Wright left for Europe. Although he offered to leave the studio’s commissions to Mahony, she declined. However, she was subsequently hired by Wright’s successor under the condition that she was in full control of the design. She was furious with Wright abandoning her, their firm—and for destroying the intimate friendship she shared with Wright and his wife, Kitty. In The Magic of America, Marion’s never-published memoir, which she wrote from 1938 to 1949 in a race against the onset of dementia, the bitterness she still felt against Wright was tangible. “When the absent architect didn’t bother to answer anything that was sent over to him, the relations were broken.”

A Perfect Marriage

In 1911, Marion married fellow-architect Walter Burley Griffin (1876-1937), an associate of Wright’s, and they set up a joint practice. In 1912, Marion executed 16 renderings for a contest for the city design of Canberra, the site of the new capital of Australia. Walter won.

Actually, it was Marion who won but the couple were of the same mind that if her name appeared on the plans, it would trivialize the entry—a sad reflection of a different time.

“I want people to know her name. To just know that she existed, that she was a fantastic architect, designer, artist, and environmentalist in her own right,” says Kathleen James-Chakraborty, a scholar of Marion’s work. “Of the two (Marion and Walter), Marion was the most closely tuned to nature and Canberra is a city that sits within the landscape.”

Walter and Marion Griffin

“She then spent her life making Walter look good,” explains Glenda Korporaal, author of Making Magic: The Marion Mahony Griffin Story. However, despite choosing the subservient role, Marion had engaged in a marriage that fulfilled her both professionally and personally and was content to describe herself as “Walter’s useful slave.” In 1914, the Griffins arrived in Australia so Walter could oversee construction of the new capital city. It was not easy. A foreigner, at first, he was confronted by builders and bureaucrats who defied taking orders from an American architect. However, by completion the project was a grand success. Marion and Walter would remain in Australia for several more years to design and supervise the building of the New South Wales towns of Griffith and Leeton “Truly I lost myself in him,” she wrote in her memoir, “and found it completely satisfying.”

In 1935, Walter traveled to India to work on the Lucknow University Library. Marion remained behind to oversee the completion of several projects and joined him the following year. This marked the final chapter of their incredible partnership. He died, suddenly of peritonitis after gall bladder surgery in 1937, at King George’s Hospital in Lucknow. After his death, a bereaved Marion remained in India long enough to complete the Pioneer Building, transferred the India branch of their practice to their partner, Eric Milton Nicholls, and returned alone to Chicago. In the 28 years they had lived, loved, and

worked together, the couple designed over 350 buildings, landscape and urban design projects, were involved in the fabrication of new construction materials, and designed interiors, furniture, and other household items.

For all intents and purposes, it was over. Theirs had been a supremely happy and rewarding marriage; but like a pair of mating swans, who mate for life, when one dies the other will perish of heartbreak. Marion’s heartbreak lasted 24 years. She never practiced architecture again. Her brilliant mind deteriorated from dementia, and she lived in poverty until, alone, she died destitute at the age of 90. Where her ashes are interred is not known. There is no marker. But in death, faith tells us she will be reunited with her husband, forevermore. What comforts, nonetheless, that the work of this great architect is finally remembered—and lives on.