Good habits are easy to break, whereas bad or unhealthy habits seem to be a bit more difficult, and addictions even tougher. According to Wikipedia, addiction is “a neuropsychological disorder characterized by a persistent urge to engage in behavior which produces a natural reward, despite substantial harm and consequences.”

Addictions are often discussed in terms of alcohol, tobacco use, marijuana, and obviously, illicit drugs. However, addictive behavior is not limited and can also encompass shopping, gambling, sex, prescription medication, and even eating disorders.

Addiction is considered a chronic disease influenced by biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Fundamentally, there is normally not a single cause of addiction.

A significant part of how an addiction develops is through changes in brain chemistry. Certain activities (and substances) affect the brain, and especially the reward center. Humans are biologically motivated to seek reward; thus, addictions can form based on emotional needs and habits. Food is one source which can become emotionally companionable, leading to eating disorders and addictions, comparable to drugs and alcohol.

Surprisingly, statistics show the number of adults in the United States considered to have Binge Eating Disorders (BED) is three to four million, constituting three to four percent of all adults.

“There are many terms used to describe disordered eating, including food addiction, emotional eating, and compulsive overeating. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5), a clinical reference published by the American Psychiatric Association, considers BED as a clinical diagnosis,” said Rosezina Meadows, LPCC-S, PhD, who has practiced mental health counseling (addictions) for more than thirty years.

“This clinical recognition is crucial, as it brings awareness, resources, and help for those who are struggling,” added Meadows.

One component of food addictions and/or eating disorders in this country are driven by cultural influence and celebratory habits of Americans.

“From an early age, we equate food with managing emotions. For example, when someone passes away, food is a part of the ceremony after the service. For a graduation celebration, wedding, or a birthday, food is a component. As children, when we fall and scrape our knees and cry, it is not unusual for a parent to have given us an ice cream to comfort us,” added Dr. Meadows.

Symptoms of a BED could include:

• Feeling disgusted, depressed, or extremely guilty after overeating

• Eating until feeling uncomfortably full

• Eating substantial amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry

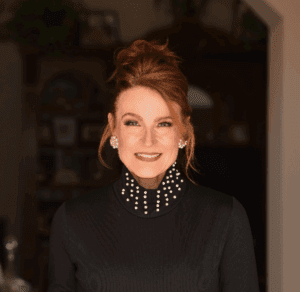

Meet my friend, Stacy Landon, who agreed to discuss a distressing trauma which led to her eating disorder. For that matter, the idea for this column came from her experience.

At age 28, Stacy suffered the anguish of losing her younger sister, and within only a few years, she had gained 35 pounds.

“My sister passed away in May 2001. The grief took a toll on me personally, while also carrying much of my parents’ grief,” said Stacy Landon, an executive assistant at L3Harris Technologies, an aerospace and defense company. “I became a stress snacker, which became a huge problem. Along with going out on the weekends, fast food becoming the norm, not exercising, socializing, and casual alcohol, it all led to an unhealthy lifestyle.”

Landon said she succumbed to the overwhelming demands of life and loss, and after becoming a mom, she was 240 pounds by her late thirties.

“I tried Jenny Craig, Weight Watchers, and other weight loss options, but all failed. I tried injections and lost a maximum of 20 pounds, but could not keep it off,” added Landon.

Due to her struggles, her doctor suggested she would be a suitable candidate for surgery. This year, January 2025, marked ten years of her post-bariatric sleeve journey.

“Over the years, I had maintained my weight loss of 115 pounds. Until the past year, due to perimenopause and other health-related matters, I have gained 10 pounds but am actively working to lose the weight,” said Landon.

I asked Stacy if she could go back in time and do it all over again, what would she have done differently?

“I would have sought help and counseling sooner. I would have taken better care of my mental and physical state and been more accepting of my situation instead of ignoring it out of fear or facing reality and feeling like a failure. Once I became obese, I did not know how to recover, so I gave up. I was succeeding in all other areas of my life, career, family, and raising a daughter, but I had clearly lost sight of my physical, mental, and emotional health,” added Landon.

As part of Stacy’s surgery and recovery, she underwent therapy. She learned this process was not just about emotions and food, but a work-life balance, while placing herself as a priority.

“I have finally obtained a level of confidence I never had. I no longer feel judged while in public, or criticized for being overweight, and all the negative thoughts which hit our brains while living with obesity,” added Landon.

Comparable to Stacy’s story, research indicates food addiction affects one in eight Americans over 50 years of age (13 percent), according to the University of Michigan. Food addiction is also estimated at approximately 12 percent among adolescents in the U.S., with women being more likely to develop these disorders than men.

Meadows referenced there are multiple options to addressing addictive eating: “Psychotherapy is usually the foundation for the best treatment plan. In most cases, collaborating with a psychiatrist is best when medication is needed. For example, some individuals with a BED also have underlying mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, or ADHD.”

Luckily, my friend (Stacy) was able to emotionally identify the cause of her weight gain. She took the appropriate steps necessary for surgery (and counseling) and became victorious in her weight loss.

If you or someone you know might be suffering from an eating disorder, Dr. Meadows recommends www.nationaleatingdisorders.org, or www.nimh.nih.gov for further information.

by Lisa F. Crites