Women Artists — From Old Masters To Those Just Out Of Art School — Have Slowly Gained Traction In Museums And On The Art Market For Years. If You’re Thinking Of Collecting Art By Women, Now Is The Time.

By Kate McQuaid

In the early 1970s on a trip to Venice, Wilhelmina Cole Holladay purchased a still life painted by Clara Peeters, a contemporary of Rembrandt’s. Captivated, Holladay tried to research Peeters and found very little. The painting was an early piece in an extensive collection of work by women, which would lead led Holladay and her husband Wallace to found the National Museum of Women in the Arts, opening in 1987.

It wasn’t until 2016 that Peeters had her first monographic show at the Museo del Prado—the Prado’s first exhibition devoted to a woman painter.

“The value of her work has gone up, not only on the market, but recognizing the value of her style of painting,” says Virginia Treanor, associate curator at NMWA. “She was among the first to do what are known as breakfast paintings—a catchall term for still life paintings of food.”

Women artists—from old masters to those just out of art school—have slowly gained traction in museums and on the art market for years. If you’re thinking of collecting art by women, now is the time. This year appears to be a watershed.

“Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future,” an exhibition of work by the Swedish modernist that closed in April, shattered records at the Guggenheim, pulling in 600,000 viewers.

In January, Victoria Beckham joined forces with Sotheby’s during Masters Week to spotlight 21 works by 14 women in a show called “The Female Triumphant,” including gold-standard artists such as Artemisia Gentileschi and Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun. Sales exceeded estimates, realizing $14.6 million.

The fever for women artists is even coming to television. This spring, Amazon optioned Mary Gabriel’s 2018 book Ninth Street Women for Emmy winners Amy Sherman-Palladino and Daniel Palladino to develop as a series. The book spotlights Elaine de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan and others in the postwar New York art scene.

“The rising demand for their work, both curatorially and commercially, is indicative of centuries-delayed ‘canon correction,’” according to Mary Sabbatino, vice president and partner at Galerie Lelong & Co, which has had a balanced roster of male and female artists since its founding in the late 1980s.

The attention is driving up value. If you want to purchase, say, a Hartigan painting before Ninth Street Women premieres, this would be a good time to invest.

“Art outperformed the stock market in 2018,” says Julia Wehkamp, co-founder of One Art Nation, an educational platform for collectors. “People are looking at it more seriously as an investment option.” The 2018 U.S. Trust Insights on Wealth and Worth survey conducted by Bank of America found that the proportion of its clientele of high net worth women investing in art more than doubled from the previous year—from 16 percent to 36 percent.

“I’d like to think more women who collect are paying attention to the disparities and see an opportunity to make a more accurate art historical record,” says independent curator Melissa Messina, who organized “Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today,” a recent traveling exhibition spotlighting abstraction by women of color.

Collecting art takes passion, and it takes work. If you’re put off by the head-scratching research, the hushed austerity of white cube galleries, the competitive bustle of art fairs or the prospect of competitive bidding at auction, Wehkamp recommends hiring an art advisor.

An advisor will do the research for you—crucial if you’re collecting pre-World War II art. Art by women is harder to find; there’s less scholarship, and unlike art by men, it wasn’t historically collected or celebrated. It got squirreled away in private collections. You’ll need someone savvy about issues of conservation and provenance.

“It’s more exciting to have something with history, but it still could have been stolen by the Nazis,” says Frima Fox Hofrichter, professor of history of art and design at Pratt Institute.

Advisors analyze the market, bid at auction for you and negotiate with galleries. High-end galleries may have preferred client lists that can be hard for new collectors to crack; experienced advisors know how to get in the door. They typically charge five to ten percent on top of a sale price or accept a flat monthly or yearly retainer.

But be careful whom you choose.

“Anyone can call themselves an art advisor. Until now, no education has existed about managing conflicts of interest, like a paid connection to a gallery,” says Wehkamp. One Art Nation has vetted its affiliates and offers best practices courses for advisors. Another resource is the Association of Professional Art Advisors, whose members follow a code of ethics.

“Ask what experience does she bring to the table, and who has she worked with,” Wehkamp recommends.

These days, art collectors don’t have to visit a gallery. The U.S. Trust survey noted that women are more likely than men to buy art online. Instagram is a great way to scout contemporary artists. Some even eschew gallery representation and peddle their own work there.

Independent curator Lolita Cros organizes women-only shows for The Wing, a nationwide network of women’s work and community spaces. Her exhibitions mix emerging and established artists. If you’re looking at emerging artists, she recommends attending open studios events and thesis exhibitions at art schools. She visits artists’ studio and posts what she finds on Instagram and YouTube.

Social media, she counsels, can be a double-edged sword.

“I find a lot of artists on Instagram,” she says. “When I like their art, I pick up the phone and go to the studio. Sometimes when I see it in real life, I’m not moved.”

Artists selling art from their studios or online can have a lower price point. When they get gallery representation, their value can soar. At the same time, an artist without a gallery may be a riskier investment. Dabble and learn.

If you’ve never bought art before, Cros advises, “Don’t start with a work that’s $50,000.”

Either way, it’s important that the art touches you. The stocks you invest in may represent your values. The art you invest in should speak to your soul. That’s true if you’re buying work by an old master or a newly minted MFA.

“First, buy what you love,” says Wehkamp. “It’s not sitting in a portfolio. It’s hanging on your wall.”

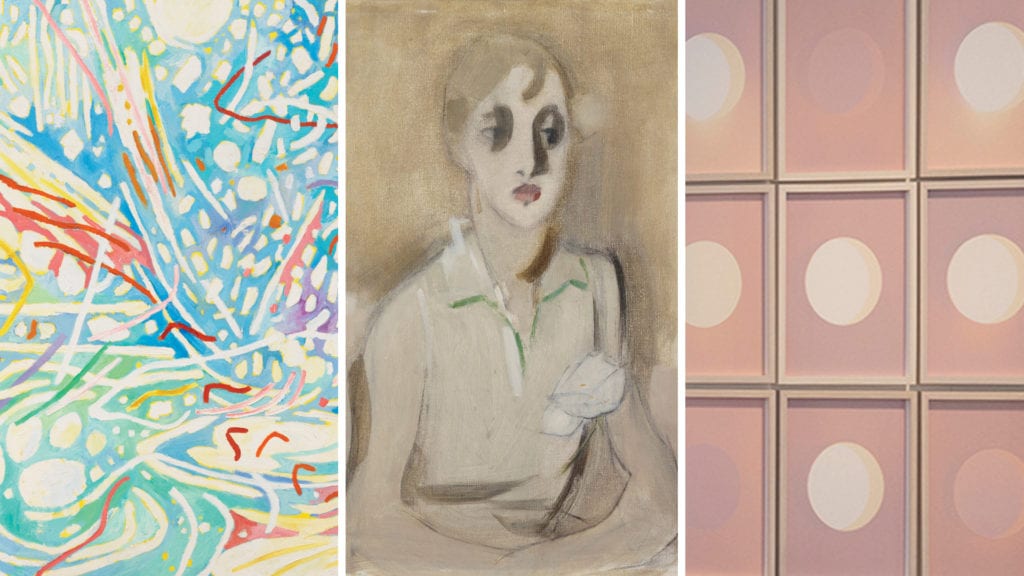

Left to Right: Mildred Thompson, Radiant Explorations; Helene Schjerfbeck, Modern Schoolgirl; Rachelle Bussieres

Three artists whose stock is on the rise:

Mildred Thompson

1936-2003

Thompson’s abstract canvases pulse with steamy colors and streaming gestures. “The content reflects her interests in science, cosmology, theosophy and natural phenomena,” says independent curator Melissa Messina, who included Thompson’s paintings in “Magnetic Fields.”

Now, the art world is interested in Thompson, who worked in relative obscurity. In the 1990s, when curators were looking to African-Americans to make work about being black, Thompson’s paintingsdelved into music and string theory.“Mildred, despite not receiving recognition, always knew she was making an impact. And she didn’t care if anyone else recognized that. She knew who she was,” Messina says.

Helene Schjerfbeck

1852-1946

The Finnish modernist is finally garnering major attention outside of Scandinavia with a solo exhibition this summer at the Royal Academy in London that traces her evolution from naturalism to stark, abstracted self-portraits.

“People are going to start integrating her into a broader narrative. When they think of Munch, they’ll think of Schjerfbeck,” says Jeremiah McCarthy, associate curator of the American Federation of Arts, which organized “Women Artists in Paris 1850-1900,” a recent exhibition that included work by Schjerfbeck.

“She was making simplified, stylized modern paintings that showed the influence of fashion plates, of modern life,” says McCarthy. “People were not ready for her at all.”

Rachelle Bussières

b. 1986

Bussières, a Québécois, was working in San Francisco when Lolita Cros tapped her for an exhibition at The Wing in that city. She recently resettled in New York. Her mystical abstractions are lumen prints—photographs developed with sunlight over a period of time, using forms to block the light. “She’ll put a circle down at noon and come back three hours later and shift it,” says Cros.

“The intensity of the light changes the effect,” says Cros. “The ones she made in California were more vivid, more bright. Others she made in Nordic countries were a little more gray.”

The hard edge of the circle softens. Shadows and lights appear, creating the impression of space. Luminous forms shrouded in mist suggest an immanence—a presence within, only barely discerned.

Featured image: Installation view: “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 12, 2018–April 23, 2019. (Photographer: David Heald/©2018 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation)