The Mother of Black Feminism

“A nation’s greatness is not dependent upon the things it makes and uses. Things without thoughts are mere vulgarities. America can boast her expanse of territory, her gilded domes, her paving stones of silver dollars; but the question of deepest moment in this nation today is its men and its women, the elevation at which it receives its “vision” into the firmament of eternal truth.

— Dr. ANNA J. COOPER, “The Ethics of the Negro Question,” September 5, 1902

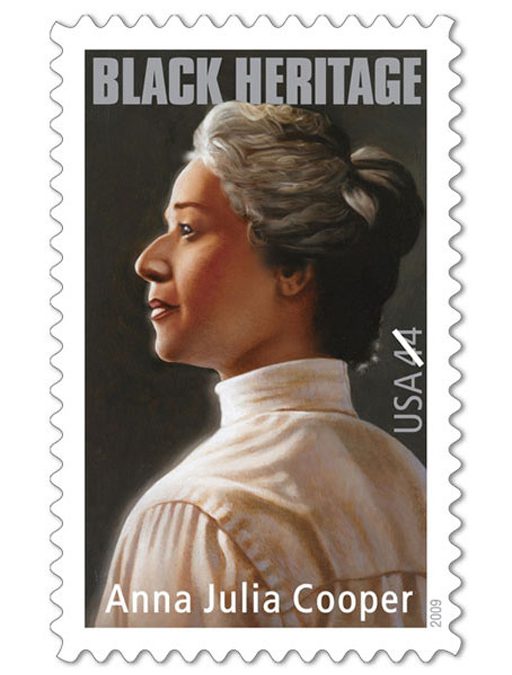

Anna Julia Haywood Cooper was an American author, educator, sociologist, speaker, Black liberation activist, college president, and one of the most prominent African-American scholars in the history of the United States. She was born into slavery in Raleigh, North Carolina in 1858. Of mixed race, her father was either her owner, Dr. Fabius Haywood, or his brother, George, both sons of the state’s longest-serving treasurers, John Haywood, a founder of the University of North Carolina. Which brother “Annie’s” mother ever refused to disclosed, but Annie worked alongside her mother as a domestic slave in the household of Fabius Haywood until the Civil War abolished slavery. The Reverend J. Brinton identified the nine-year-old as a child of superior intelligence and arranged a scholarship for her to attend and board at Saint Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute, an Episcopal school established to educate former slaves, in Raleigh. There she studied for 14 years, distinguishing herself in the liberal arts, mathematics, science, and mastering Latin, French, and Greek. Saint Augustine prepared promising male students for further education in four-year universities but women such as Annie were relegated to becoming tutors. However, the Board invited her to remain at the institution as an instructor and she taught the classics, modern history, higher English, and voice for three years until she married George A.C. Cooper, a graduate of Saint Augustine, who had gone onto earning his college degree. Annie withdrew to become a housewife but her marital happiness was short-lived. Tragically, George died two years later.

Determined to continue her education, the young woman was accepted at Oberlin College in Ohio in a degree course delegated for men. So high were her academic qualifications that she was admitted as a sophomore, graduating in 1884. She would earn her master’s degree in mathematics from Oberlin in 1888—one of the first two Black women, along with American activist and suffragist Mary Church Terrell, to receive an M.A. in American history. During her years at Oberlin she wrote the first of many books and discourses, A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South, which was published in 1892. She presented her paper, “The Intellectual Progress of the Colored Women of the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation,” at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in Chicago—one of only five African-American women to be invited to speak.

Determined to continue her education, the young woman was accepted at Oberlin College in Ohio in a degree course delegated for men. So high were her academic qualifications that she was admitted as a sophomore, graduating in 1884. She would earn her master’s degree in mathematics from Oberlin in 1888—one of the first two Black women, along with American activist and suffragist Mary Church Terrell, to receive an M.A. in American history. During her years at Oberlin she wrote the first of many books and discourses, A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South, which was published in 1892. She presented her paper, “The Intellectual Progress of the Colored Women of the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation,” at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in Chicago—one of only five African-American women to be invited to speak.

She moved to Washington, D.C. and with several other Black women of high academic achievement formed the Colored Women’s League, a service organization that promoted unity, social progress, and opportunity to the African-American community. In 1900, she made her first of several trips abroad, to participate in the First Pan-African Conference, and delivered a paper entitled, “The Negro Problem in America.” From London she embarked upon a Grand Tour of Europe. In 1914 at the age of 54, Annie entered Columbia University in New York to study for her doctoral degree but a family tragedy caused her to temporarily interrupt her studies. She succeeded in transferring her credits, but not her thesis, from Columbia and resumed her studies at the University of Paris-Sorbonne. Finally, in 1924, she completed her coursework and successfully defended her thesis, “The Attitude of France on the Question of Slavery Between 1789 and 1848,” and was awarded her doctorate in 1925. She was 65-years-old when she became the fourth Black woman in American history to earn a Doctor of Philosophy degree.

Annie returned to America and taught at Washington Colored High School for five years, throughout which she continued her political activism. In 1930, she accepted the position of president of Frelinghuysen University, where she remained for twenty years. By the time of her death on February 27, 1964, in Washington D.C. at the exalted age of 105, Dr. Anna J. Cooper had long emerged as a trailblazer who broke the physical and societal shackles of race to lead African American women—indeed, all women—through a wilderness where no path had been forged for our sex to follow. For this reason, we honor Dr. Anna J. Cooper for Black History Month.