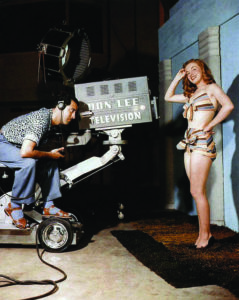

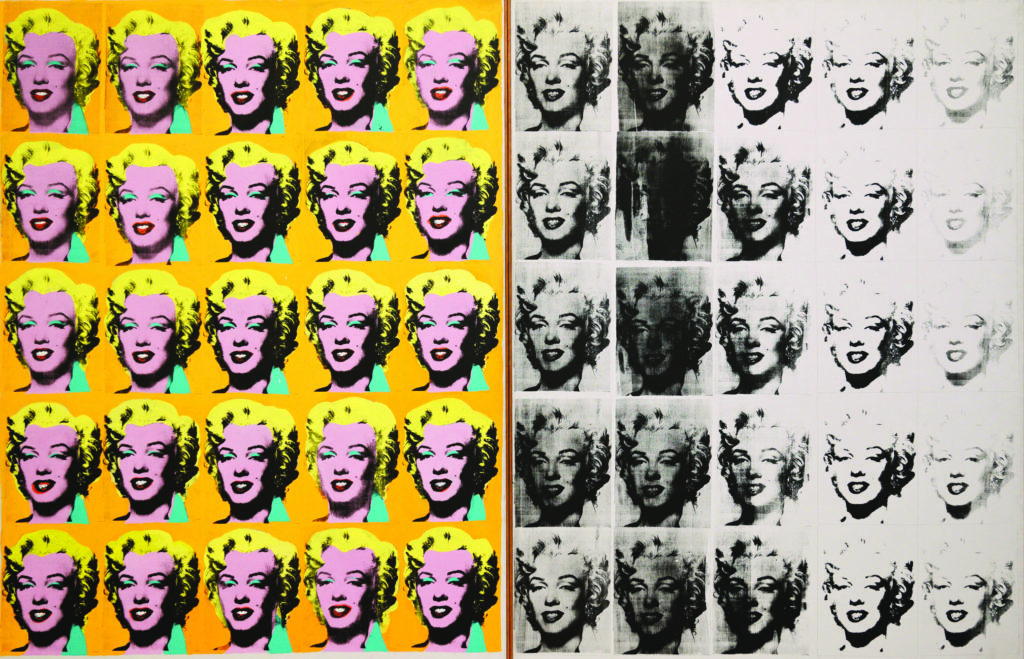

She is the world’s most enduring iconic female figure, the inspiration behind more than 1,000 books, countless articles, songs, and innumerable films; the muse of Andy Warhol, and the model for such great photographers as Eve Arnold, George Barris, Cecil Beaton, Milton Greene, Bob Henriques, and the last to capture her on film, Leif-Erik Nygards, two months before her death. In 1962, at the age of 36, she was no closer to understanding who she truly was than on June 1, 1926, when she was born to Gladys Pearl Baker Mortenson Eley, a 24-year-old divorcee diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, in the charity ward of Los Angeles County Hospital. Unable to care for herself let alone a child, Gladys was committed to the state mental hospital and was institutionalized until her death in 1984, 22 years after her daughter’s. The identity of Norma Jeane’s biological father remains unknown. To the scarlet letter of illegitimacy in those days, Gladys gave the name of the father on the birth certificate as Martin Edward Mortensen (misspelled Mortenson) who, according to urban legend, bought a motorcycle and headed north to San Francisco after Gladys told him she was pregnant and was never heard of again. According to the timeline and birth certificate, however, Mortensen could not have fathered the child. Though he and Gladys had briefly been married for seven months, Norma Jeane was conceived three-and-a-half-months after the couple separated and ten days after their divorce was final. It is believed that Norma Jeane’s biological father was Charles Stanley Gifford, a shift foreman and Glady’s boss when she worked as a film-cutter at Consolidated Film Industries before she gave birth to the child—speculation that nears the truth when you compare Marilyn’s striking resemblance to Gifford and impossible likeness to Mortensen. In adulthood, Marilyn believed Gifford was her father from a photograph she remembered her mother showing her as a child, telling her “This is your father.” Even after she was a star, Gifford rebuffed her attempts to contact him.

This was the beginning of a tumultuous, cruel, Dickensian childhood rampant with physical and sexual abuse in orphanages and foster homes until she was 16, when a 21-year-old Merchant Mariner named James Dougherty agreed to marry her rather than have her face a return to the orphanage. He was posted to the South Pacific when he received news Norma had divorced him. One of Hollywood’s biggest film studios, 20th Century Fox, offered her a contract on the proviso the 19-year-old aspiring starlet was unmarried. Years later Dougherty became a detective with the Los Angeles Police Department and the first officer trained for the newly created Special Weapons and Tactics Group (he broke a plot to kidnap actor James Garner). In a 2002 interview with Associated Press, he said of his ex-wife, “Fame was injurious to her. She was too gentle to be an actress. She wasn’t tough enough for Hollywood. And once someone starts getting into pills—uppers and downers, the way she was—people can go downhill. They can’t sleep, so they take more and more pills.” Dougherty more than anyone else in her life would come closest to knowing the tormented creature, because he and he alone in her life, knew her as a teenager who grew into adulthood, and as Norma Jeane, who transformed herself into Marilyn Monroe.

“There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

– Leonard Cohen

Kintsugi, or “golden joinery,” is the ancient Japanese art of taking a broken tea bowl or other piece of treasured pottery and putting it back together with lacquer dusted with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. It is a metaphor for self-development, resistance, and a symbol of healing, and that imperfection and fragility should be celebrated. Rather than disguising the breakage, the repair becomes part of the object’s essence. “Our bodies and minds have an innate drive to repair, and this forces us to keep going, and to recognize that this repair is as important as the break itself,” wrote Candice Kumai in her book, Kintsugi Wellness: The Japanese Art of Nourishing Mind, Body, and Spirit (2018.)

Marilyn Monroe was broken throughout her childhood. Had she known the concept of kintsugi, she might have been able to put back the broken pieces, heal, and see her beauty as something other than perfection—but alas, she did not. She was intelligent, however, with a consummate desire to improve herself. Indeed, when she left her first marriage she owned 400 books, each of which she had thoroughly read.

As Marilyn Monroe, she was a hard-driven, insecure woman with no self-confidence and a consummate need to achieve acceptance, perfection, and love. She diligently kept a diary she called “Red,” which was not discovered until sometime after her death. These passages reveal the flawed woman the world saw as flawlessly beautiful. The progression of her entries corresponds with her development as an actress. Always the sexy, dumb blonde, she played bit, usually uncredited parts in a back-to-back string of forgettable films, such as Dangerous Years and The Shocking Miss Pilgrim in 1947, Sudda Hoo! Scudda Hay, Green Grass of Wyoming, and Ladies of the Chorus in 1948, Love Happy in 1948 with the Marx Brothers, and in 1950, A Ticket to Tomahawk, Right Cross, and The Fireball. That same busy-crazy year, however, she took on small but important roles in two movies that would change her—and the world’s—appreciation of Marilyn Monroe as a bonafide actress: director John Huston’s film noir, The Asphalt Jungle, and director Joseph L. Mankiewicz sizzling cat fight, All About Eve, pitting Bette Davis against Anne Baxter with Marilyn smack in the middle. Acting among greats made her determined to become a headline star and not just a backlot beauty.

She filmed nine unremarkable films between 1950 and 1951 but things changed up exponentially for Marilyn in 1952, when she was cast opposite Hollywood heavyweights Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers in the Howard Hawks comedy, Monkey Business. Now the movie-going public demanded more and more of the smoldering blonde and her cleavage. The studio went full throttle to exaggerate her as Hollywood’s greatest sex goddess. In 1953, she got top billing in two back-to-back hits, How to Marry a Millionaire and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. But it was that very same year that Marilyn ventured upon her first departure toward becoming a serious dramatic actress, taking on the role of Rose Loomis in Niagara, opposite one of motion pictures’ most enduring actors, Joseph Cotton. And the following year, she starred opposite one of the few actors who could withstand the heat of Marilyn’s seething, on-screen sexuality— Robert Mitchum, in Otto Preminger’s River of No Return.

However, Hollywood and her infatuated public would not allow Marilyn to venture into deeper waters and she continued to play the sex goddess in The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Some Like It Hot (1959.) But between the two comedies, in 1957, she filmed The Prince and the Showgirl opposite an aging Sir Laurence Olivier and something happened: unwilling to stand in the shadow of the great Shakespearean actor, Marilyn stole the show. Now she was determined more than ever before to become a great actress. Her chance did not come in 1960 when she starred with French heartthrob Yves Montand in the lukewarm George Cukor comedy, Let’s Make Love.

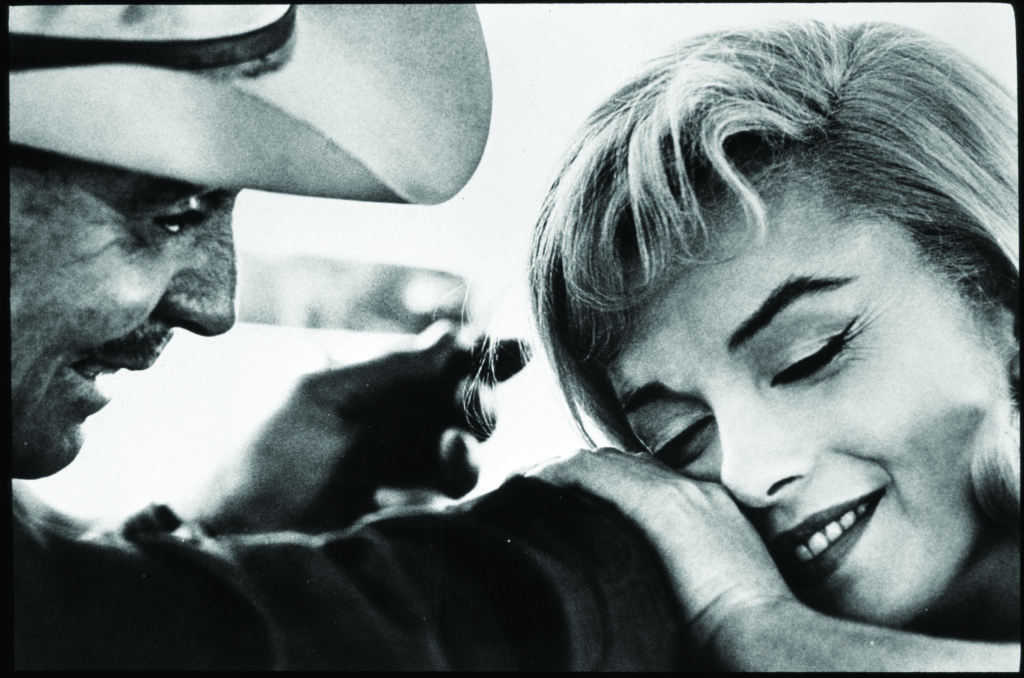

It did come, however, in 1961 when she starred opposite her alltime idol, Clark Gable, working again with director John Huston in The Misfits and also staring Montgomery Clift. Marilyn, who was usually late or AWOL for her scenes and frustratingly difficult to work with, had been experiencing deep and reoccurring bouts of depression over her deteriorating third marriage, to writer Arthur Miller. As a result, the production experienced lengthy delays, was physically grueling and difficult to make, taxing everyone involved in front of and behind the camera beyond endurance. The day after the film wrapped, Clark Gable died of a massive heart attack—just months shy of the birth of his only child, a son. Marilyn blamed herself for Gables’ death. It was the last motion picture she would ever make.

In Her Own Words

She said of the notebooks she began writing as “not exactly a diary… sometimes when things used to happen, I used to write it down. As a small child, my first desire was to be an actress,” Marilyn confided, but as the years and parts evolved, so, too, her desires: “I would like very much to be a fine actress. I would like to be happy but trying to be happy is almost as difficult as trying to be a fine actress.”

Completely controlled by the studio system, she wrote, “I am not permitted problems, nervousness, humanness, and my own thoughts,” and in defiance of her unhappy reality, added, “Dare not to worry. Dare to let go.” Starving for some sense of security, she wrote, “There’s nothing to hold onto but to realize the present.”

In 1955 she left Hollywood to work closely with legendary acting coach Lee Strasberg in New York. If her dream to become a great actress was to come true, she had to return to her childhood fears, he explained. She called him the “best, finest surgeon. Strasberg cut me open, which I don’t mind, since (like a doctor) he has prepared: an operation to bring me back to life and to cure me of this terrible disease, whatever the hell it is.” To accept herself fully she could no longer repress her painful memories. She started psychoanalysis, reliving the episodes of sexual, physical, and mental abuse she suffered in foster homes and orphanages in her childhood. Of one woman, a strict Evangelical Christian named Aunt Ida, with whom she lived on and off, she wrote: “Life starts from now. Ida—I have still been obeying her. It’s not only harmful for me to do so, but unreality because life starts from now. Inhibits myself, inhibits my

work, inhibits thoughts. In my work I don’t want to obey her any longer and I can do my work as fully as I wish since, as a small child, (my) intact first desire was to be an actress and I spent years play-acting until I had jobs. I will not be punished, or try to hide it, enjoying myself as fully as I wish or want to. I will be as sensitive as I am without being ashamed of it. Trust in the faith in the simple objects and tasks. Sense memory, outside and inside objects, I haven’t had faith in life, meaning reality—whatever it is, or happens, there is nothing to hold on to but reality, to realize the present, whatever it may be because that’s what it is and it’s much better to know reality or things as they are than not to know, and to have few illusions as possible. Train my will now.”

Living at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, she spent hours poring over her diary as she tried to understand herself and lay to rest her fears:

“Working doing my tasks that I have set for myself on the stage I will not be punished for it or be whipped or threatened or not be loved or sent to Hell to burn with bad people feeling I am also bad or be afraid of my genitals being . . . or ashamed, exposed, known and seen so what? Or ashamed of my sensitive feelings? They are reality or colors or screaming or doing nothing and I do have feelings, very strongly sexed feelings since a small child. I think of all the things I felt then. I do know ways people act unconventionally, mainly myself. Do not be afraid of my sensitivity or to use it. For I can and will channel it, and crazy thoughts too. I want to do my scene or exercises, idiotic as they may seem, as sincerely as I can knowing and showing how I know it is, no matter what they might think or judge from it. I can and will help myself and work on things analytically no matter how painful. If I forget things, the unconscious wants to forget, and I will only try to remember. Discipline, concentration. My body is my body, every part of it. I feel what I feel within myself that is trying to become aware of it, also what I feel in others. Not being ashamed of my feeling thoughts or ideas realize the thing that they are. When I start to feel suddenly depressed, what does it come from? In reality, trace incidents, maybe to past times. Feeling guilty realize all the sensitivity aspects, not being ashamed of what I feel, don’t dismiss this lightly. Not regretting what I said if it’s really true to me, even when it is not understood. Don’t even try to convince anyone too much as to why unless I really want to, or really feel it. Tension. Where do I feel it? Be aware of it. What and where do I think it comes from? Make effort to be aware, like when feeling sick. Try to stop chain reaction before it gets started if it does start. Don’t worry, realize it. Be aware of it, consciously making the effort; consciously making the effort to relax brows, temples, area around mouth, collapse cheeks, shoulders, jaws hanging loose, having sense of myself.”

The Canvas Wiped Clean

The front page of the New York Mirror on August 6, 1962, blared: “MARILYN MONROE KILLS Self—found Nude in Bed. Hand On Phone . . . Took 40 Pills.” The Los Angeles County Coroner’s Office, assisted by the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Team, investigated. Her doctors stated that Marilyn “had been prone to severe fears and frequent depressions [with] abrupt and unpredictable mood changes” and had overdosed several times in the past, possibly intentionally.” There was no indication, at first, of foul play.

Her final diary entry illustrates the very soul of this beautiful, complex, woman as if it was her last—and, for this writer, at least, surely must be:

“That silent stirring river, that river which stirs and swells itself with whatever passes over it—wind, rain, great ships—I love the river . . . I love the river, never unmoved by anything. It’s quiet now and the silence is alone except for the thunderous rumbling of things unknown. Distant drums very present but for the piercing of screams and the whispers of things, sharp sounds, then suddenly hushed to moments beyond sadness. Terror beyond fear. The cry of things dims, and too young to be known yet. The sobs of life itself. You must suffer to lose your dark golden when you’re covering up; even dead leaves leave you strong and naked. You must be alive when looking dead, straight though, bent with wind and bare the pain and the joy of newness on your limbs: loneliness, be still. I stare down at you like a horizon—the space, the air is between us beckoning. O, Time, be kind. Help this weary being to forget what is sad. Lose my loneliness, ease my mind, while you eat my flesh.”

By Laurie Bogart Wiles