Female Equestrians that Are Leading the Charge in Each of the 8 Disciplines Featured at the World Equestrian Games

By Pam Stone

Held every four years in the middle of the Olympic cycle since 1990, the World Equestrian Games brings its eight disciplines and more than half a million spectators to the foothills community of Tryon, N.C., beginning Sept. 11.

Unlike most sports, men and women compete with and against each other in every event: Show Jumping, Three Day Eventing, Dressage, Para Dressage, Reining, Vaulting, Endurance and Combined Driving. The Cross Country isn’t less grueling for the fairer sex, the Show Jumping less dangerous. The women arriving with their 1,300-pound partners, often valued in excess of a million dollars, aren’t looking to be placed upon a pedestal. But stepping onto the podium for a medal is a different story. We profile America’s best.

LAURA GRAVES

LAURA GRAVES

[D R E S S A G E]

There are those who might argue that the classical properties of the art form were lost when dressage became a sport, but watching world-class competitors at the World Equestrian Games proves that this cannot be true.

One of these riders is the elegant, blonde Laura Graves, who swept the dressage categories at national competitions with her unlikely champion, Verdades. Their journey together from humble beginnings proves that equestrianism isn’t always the “Sport of Kings.”

When she was 15, Graves’ parents – after much convincing – purchased a weanling colt for the hardworking teen to raise and train herself. Verdades, or “Diddy,” though well-bred, was unruly and nearly impossible to train.

After fracturing his own jaw (and his rider’s back) at age 4, Graves tried to sell him to a trainer. He was soon returned, labeled “unrideable.” She had no option but to persevere as she dispiritedly bartended to make ends meet.

32-year-old Graves now displays trophies instead of the cosmetology license she once considered pursuing. The horse that once suffered panic attacks now channels his fear into brilliance.

In 2014, Graves was just shy of the top 15 invited to compete in the U.S. Dressage Festival of Champions in Gladstone, New Jersey – but when combinations ahead of her opted not to make the trip, she suddenly received the opportunity. Her performance would catapult Graves into the spotlight when she placed second in the championship and was selected to ride on the U.S. team in the 2014 World Equestrian Games.

In the years since, Graves and Verdades have dominated in high-profile competitions, earning a Team Gold and Individual Silver at Pan Am, a silver at the FEI World Cup, and an Olympic Team Bronze. At this year’s World Equestrian Game, the fairy tale is sure to continue.

REBECCA HART

REBECCA HART

[P A R A D R E S S A G E]

In 1998, Rebecca Hart’s first para-dressage competition presented quite the challenge. Imagine mounting a horse you’ve never ridden, having only a few hours to get comfortable and then riding into a packed stadium. “And those horses weren’t para horses,” Hart recalls. The donated horses were not trained to respond to commands given by the weight, core and hands of a para rider.

Hart is quick to point out that “para” is not derived from “paraplegic” and does not evoke disability – it’s a parallel sport, held to the same FEI standards.

Born with hereditary spastic paraplegia, Hart was frustrated with her legs’ muscle deterioration. “When you’re a child,” she explains, “you have this sort of magic thinking, ‘I’ll do this sport and be like everyone else.’ Then you realize it’s not going to happen.”

Hart soon found new legs: horses. “They didn’t look at me as having a disability,” she reminisces.

Retiring her first international horse Norteassa after the 2008 Para Olympics, Hart struggled with her identity as her original sponsor Margret Duprey was unclear about continuing. “A horse without a rider is still a horse,” she says, “but a rider without a horse is just a person.”

Fate arrived in the form of Rowan O’Riley, who sponsors not only Hart but the sport as well. His commitment brought her two new horses: El Corona Texel and Fortune 500. On “Tex,” Hart has achieved multiple wins and impressive scores.

Hart comes to Tryon with a lucky charm: a compact from her sister with a heart glued to the mirror. “The story goes that I touch the heart, and I become superhero Equestra,” she laughs. And her goals for WEG? “To be on that podium,” she says without hesitation, not only for herself but for everyone who helped make her dreams come true.

LAUREN KIEFFER

LAUREN KIEFFER

[E V E N T I N G]

Having once described riding cross-country as “going into battle,” Lauren Kieffer preps herself with an iPod in one hand and a Red Bull in the other.

Three-day eventing is arguably the most grueling discipline. Sandwiched between dressage and show-jumping, the second day holds a demanding endurance test. Riders must guide their mounts across four miles and 40 obstacles. Only the rider walks the course beforehand, so the fearless obedience of the horse is tested when the time comes.

Considering his own sport too dangerous, Kieffer’s dirt-bike racing father agreed to give her riding lessons for her sixth birthday. Little did they know that instead of two wheels, she would take four legs to leap obstacles that would make most parents cover their eyes.

“Ma and Papa” Kieffer understood when she chose to forego college in favor of working with Olympian riders Karen and David O’Connor. Under their tutelage, the couple allowed Kieffer to train on their horses, landing a sponsorship from candy heiress Jacqueline Mars.

Kieffer would bring home a Team Gold at the 2015 Pan American Games and an Individual Silver at the Rolex Kentucky CCI4* event. When she suffered a fall and elimination at the 2016 Olympics in Rio, she immediately reemerged herself in basics and technique.

As WEG approaches, 31-year-old Kieffer prepares her reserve horse, Veronica, nicknamed “Troll,” and her fl ashy 11-year-old Arab, Bug. She hopes to clinch another win with Bug, whom she produced herself and has been the only rider he’s ever known. “You’re never going to tell him what to do,” Kieffer says. “You have to make suggestions, and he’ll get around to deciding if it’s a good idea or not.”

BEEZIE MADDEN

BEEZIE MADDEN

[J U M P I N G]

If there is one discipline that could be inexplicably described as “sexy,” it’s show jumping. Leaping obstacles, some the size of an SUV, jumping is as breathtaking to watch as it is dangerous to compete. This is the glamorous sport of choice for daughters of American prosperity: Bloomberg, Gates, Jobs, Springsteen, Selleck…

Rising from far more modest beginnings is 55-year-old Elizabeth “Beezie” Madden. Piloting a 1,200-pound mount over more than a dozen daunting hurtles is unnerving to say the least. But the Wisconsin native was raised on a horse farm and couldn’t wait to try. In sport dominated by men, Madden was only 22 when she elbowed her way in. By 2004, she was the first woman and first American show jumper to be ranked in the top 3 in the world. In 2014, she and her horse, Cortes C, made history once again as she became the first woman to take home the prestigious King George Gold Cup at Hickstead (and returned the following year to win again).

If that isn’t impressive enough, Madden, with her ready smile, holds a truckload of medals: Team and Individual Silvers from WEG 2016; Individual Bronze and Team Golds from the Olympics in 2004 and 2008; a Team Silver in the 2016 Olympics; an astounding 17 wins at the Nations Cup; and a gold from the world-renowned Grand Prix of Aachen. Madden is the first woman to surpass $1 million in show jumping earnings. However, Madden has experienced some ups and downs – in 2014, she suffered a broken collar bone when she fell during the $100,000 Empire State Grand Prix. While her horse was unhurt, her injury required surgery, but she quickly bounced back. “It’s unfortunate, but these things happen in this sport,” she says.

When she’s not competing, Madden and her husband run an assisted living facility for horses – not only for their own retired champions, but any horse whose owners want them to live their last years grazing, rolling, dozing. In a world where equines are often seen as commodities, it’s refreshing to know that many riders put their horses first.

MANDY McCUTCHEON

MANDY McCUTCHEON

[R E I N I N G]

Born to parents that lived and breathed horses – her father, world-renowned reining competitor, Tom McQuay, and her mother, Colleen, specializing in hunting and jumping – Mandy McCutcheon was destined to pick up the reins. At age 10, she took up reining, following in her father’s footsteps.

McCutcheon’s adult life also gravitated towards the equestrian – her husband, Tom, is a renowned reigning trainer and her teammate at the 2014 World Equestrian Games. The pair brought home the Team Gold, with McCutcheon herself snagging an Individual Bronze.

“Being on a team is another level of nervous,” she recalls, reflecting on the national championships in which she’s competed (and won). “Not really that the team puts pressure on you; more that I put more [pressure] on myself not to let my team down.”

McCutcheon was the first woman and first nonprofessional rider to compete in a reining world championship, as well as the only woman reiner to earn more than $2 million from her wins. In 2011, she was inducted into the NRHA Hall of Fame.

According to McCutcheon, however, her greatest accomplishment comes from watching her children, Cade and Carlee, develop into skilled equestriennes. “Having two kids that became level 4 finalists at the NRHA Futurity at age 12 – nothing makes me more proud than when they are successful,” she says.

When asked if another World Equestrian Games is in her future, McCutcheon recalls her retired 2014 mount: “If I have another horse like Yellow Jersey, but they are few and far between.”

She still actively trains and competes, and when asked where she sees herself in 10 years, she exclaimed, “Hopefully still showing reiners!”

MISDEE WRIGLEY MILLER

MISDEE WRIGLEY MILLER

[C O M B I N E D D R I V I N G]

Should you find yourself at the combined driving event at the World Equestrian Games, you might think, “It’s so ‘Downton Abbey!’” And it kind of is. Combined driving boasts a royal pedigree: it was conceptualized by HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh after his retirement from polo. A dynamic sport described as a “triathlon on wheels,” the event is a WEG favorite.

Four horses matching in size, color, and ability, along with carriages, drivers, and grooms, are lavishly draped in traditional “Downton” finery to be scrutinized by judges before they embark on the three-phase sport.

All livery pales in comparison to the elaborate hats worn by Misdee Wrigley Miller. “I like to think hats are my signature look,” says Wrigley Miller. “When I took up combined driving, a friend told me not to be afraid to make a statement and keep wearing my large hats.”

However, lest you think this is a rather genteel sport, be warned: on the second day, helmets replace hats, and carriages are exchanged for lighter weight vehicles. Th e marathon phase, a thrilling display of speed and agility, forces drivers to guide their carriages through hazardous obstacles and find the quickest route through the course.

“As any equestrian can attest,” she explains, “size and strength don’t make any difference when dealing with horses. It is training, foundation, and understanding that allow us to ask our horses to achieve peak performance. One of the reasons I’m so committed to competing internationally at the highest level is to show other women it can be done!”

Wrigley Miller’s hopes for the 2018 Games is expected. She enthuses, “Working with my teammates to put in the best possible performance, which hopefully produces a medal, would be the ultimate!”

ELIZABETH OSBORN

ELIZABETH OSBORN

[V A U L T I N G]

Handstands, tumbling, and a 1,300-pound horse – that’s the sport of vaulting. With origins reaching back 2,000 years to Roman acrobatic games on horseback, vaulting has made a steady climb in popularity since its recognition as an FEI sport in 1983.

There’s something exciting about watching riders (garbed in elaborate unitards) perform handstands, backflips, and astonishing stretches – while mounted on a moving horse. The rider is judged on performance of seven compulsory movements, and the crowd-pleasing discipline is especially exciting when performed in squads, where members are carried and tossed in the air..

WEG vaulting competitor Elizabeth Osborn begged her parents for riding lessons, finally starting at age 9. Isabelle Parker, Osborn’s mentor and coach of 17 years, describes her protégé’s “amazing ability to move with the horse and her athletic ability.”

After attending a demonstration, Osborn was compelled to try vaulting. “It’s finding the balance between strength and harmony in the exercises,” Osborn says. For example, when standing on the horse, you must allow yourself to be relaxed and supple in order to absorb the horse’s movement, but the next move could be a handstand, in which case you need to use your strength and power to stabilize yourself.”

At Tryon, Osborn plans to emerge from a six-year retirement to compete with the 12-year-old Oldenburg, Atterupgaards Sting. “I’ve never won a national title,” she explains. “I’ve been reserve champion many times, but the national title has always eluded me.” She feels victorious about being asked to compete in WEG at all. “I would never have dreamed that I would come back to the sport after retiring at 18,” she says. “Competing at WEG in my own country and on my horse is a great honor.”

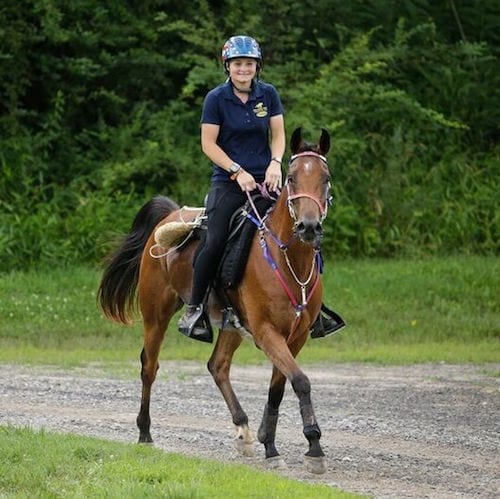

KELSEY RUSSELL

KELSEY RUSSELL

[E N D U R A N C E]

Human athletes run nearly 30 miles in marathons – but what if it was 100 miles, mapped over the terrain of the Appalachian Trail? Th is is endurance riding, and it requires tip-top condition and stamina from both horse and rider. Using maps or GPS, the pairs tackle natural obstacles like rocky hills, ditches, and streams to reach the finish line.

Saddles are light, and the rider’s attire is far from formal. Mandatory veterinary inspections every 20 miles determine that the horse is not suffering. First duo to cross the finish line and pass the vet check is named champion. So arduous is the sport that simply finishing the race is considered a triumph.

Some moments in life seem to be kismet, and the stars aligned when 13-year-old Kelsey Russell stepped onto legendary endurance champion Valarie Kanavy’s farm. It wasn’t long before Kanavy recognized that Russell was brimming with determination, talent, and most importantly, elbow grease. “She works her tail off ,” Kanavy has said of the young woman she now coaches. Her student now also manages the farm’s training program of 17 horses.

In spite of her youth, Russell, now 23, quickly became a force to be reckoned with. In 2011, she placed sixth in the World Young Rider Endurance Championships, helping her team to secure fourth place, the best American placing in a world championship since Kanavy herself took the gold in 1998.

With her career already counting 30 wins, Russell will ride into the World Equestrian Games astride 8-year-old Arabian, Fireman Gold, co-owned by Kanavy and Wendy MacCoubrey. Tryon won’t be her first WEG either – in 2014, she became the second junior rider ever to compete in the senior division of endurance riding.

Russell considers the connection between horse and rider to be her favorite aspect of the sport, so after the Games, she plans to study veterinary medicine.