Louise Nevelson (1899-1988) is widely considered the leading American sculptor of the 20th century and the originator and principal proponent of environmental art. Most closely allied with the Cubist movement of modern art, she was the original trailblazer in a world where no woman was deemed the equal of men in the visual arts. Indeed, a male reviewer of Nevelson’s 1941 exhibition at the Nierendorf Gallery wrote, “We learned the artist is a woman in time to check our enthusiasm. Had it been otherwise, we might have hailed these sculptural expressions as by surely a great figure among moderns.”

Indeed, contemporary artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Jasper Johns blatantly kept her at arm’s length and out of their inner circle. Was it jealously? Resentment that a woman had broken the glass ceiling of the international art world? Or could it be that Nevelson’s unlimited energy and uncompromising commitment to her work was like a tsunami, too much of a force to be reckoned with?

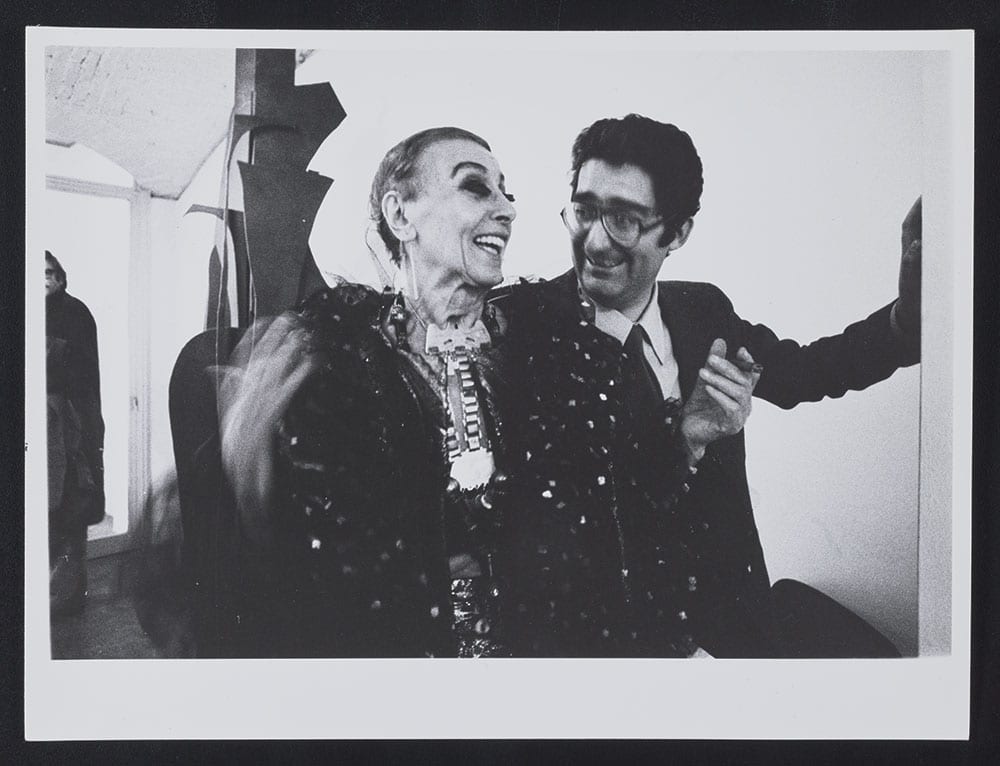

Louise Nevelson with Giorgio Marconi at Studio Marconi in Milan, Italy, circa 1973 Louise Nevelson Papers, circa 1903-1988. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

A New Life

The fact is Louise Nevelson was a risk-taker who allowed nothing to stand in the way of the originality, vision, and truth she brought to her work. Her art, she maintained, was the manifest outward expression of her personae, and in this vein, she made order out of chaos and found beauty in discarded objects. Yet, this innovative, stunningly creative, wildly independent, vibrant woman professed her art was “a matter of survival” in a society that was superficial, corrupt of spirit, and depravingly insincere.

She came upon the art scene late in her life, at a time when contemporaries such as Picasso (who she credited “for giving us the cube”), Matisse, Braque, and Kandinsky were at the height of their fame. Not until 1958 did fame finally come to Nevelson, with her first one-woman exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. “You must create your own world. I am responsible for my world,” she said. And that’s precisely what Louise Nevelson did.

Born September 23, 1899, in that part of Czarist Russia that today is Ukraine, Leah Berliawsky was the third of four children of Minna Sadie, a housewife, and Isaac, a contractor and lumber merchant. In 1902, immediately following the death of his mother, Isaac emigrated to America to join his brothers and sisters, who had fled their homeland after 1880 to avoid Jewish and political suppression. As the youngest, it had been left to Isaac to remain behind to care for their aging mother, and Minna and their three children moved to Kiev to wait for Isaac to make enough money to support a new life for the family in America.

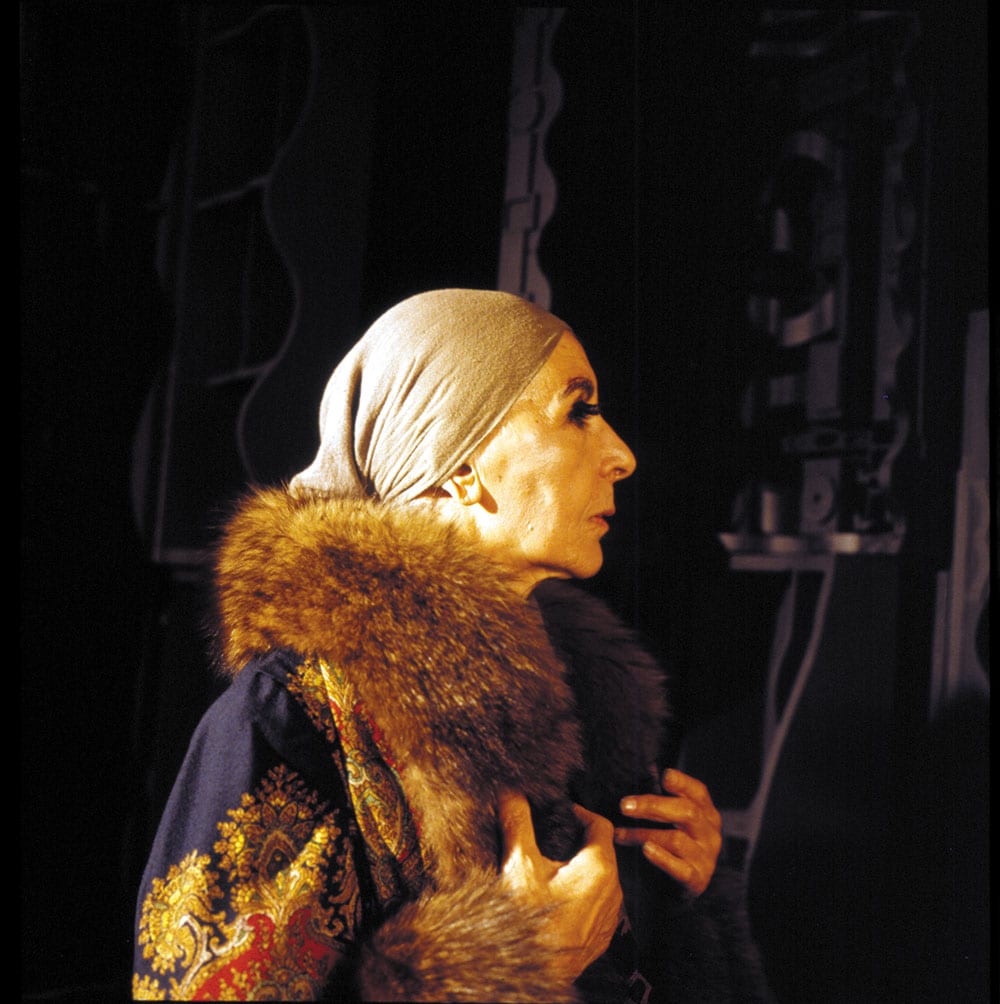

Untitled (Louise Nevelson, 1977) by Hans Namuth. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate.

Mother Knows Best

Little Leah was so distraught over the separation from her beloved father that she did not speak for six months. Three years later, in 1905, the family was finally reunited, having made their home in rural Maine, where Isaac had found employment as a lumberjack. The following year, Lillian, the fourth and last of their children, was born. Ambitious and determined to give his family a secure and comfortable life, Isaac soon opened his own lumberyard and became a successful businessman and real estate agent.

Wood, Nevelson’s medium of choice from the outset of her career, is testimony to the boundless love she had for her father. Little Leah likewise adored her mother. It had been a difficult transition for Minna to move from Jewish neighborhoods, in which she had lived her entire life, to suddenly being the only Jewish family in down east Rockland, Maine. To clothe her insecurities and alleviate the depression she now suffered, Minna dressed in elaborate outfits and heavy make-up. “She should have lived in a palace,” Nevelson would later say of her sophisticated mother. “It was her art, her pride, and her job.”

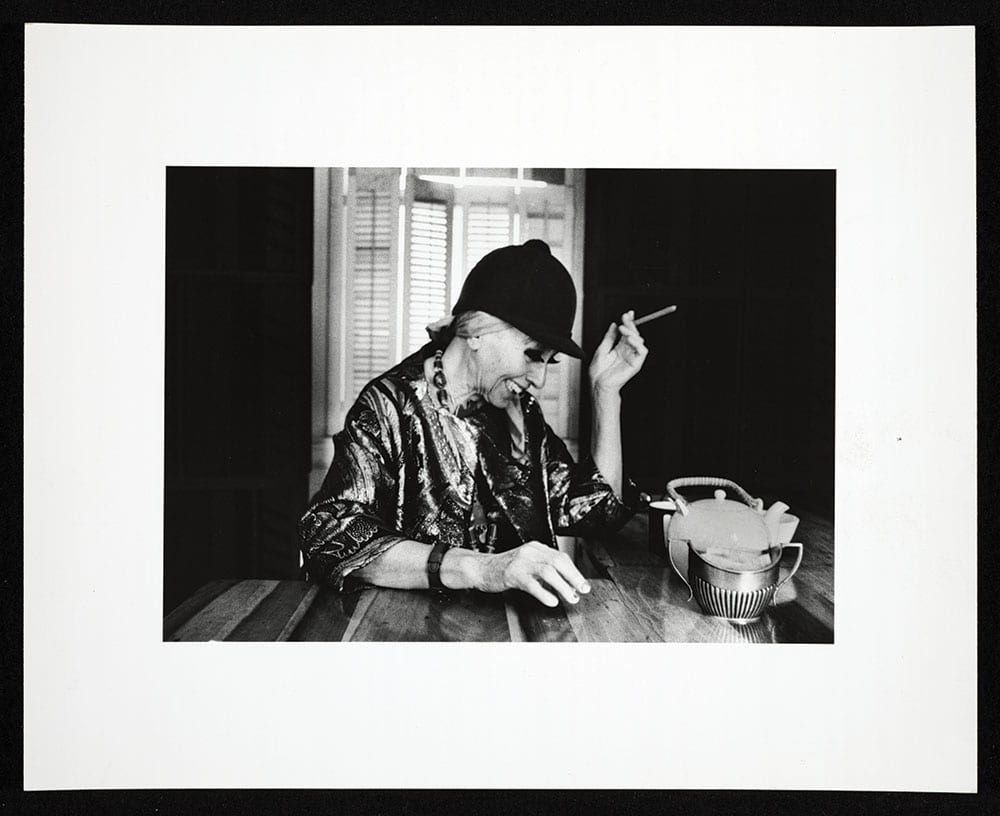

Louise would adopt her mother’s dramatic flair for clothing after she became a divorced single mother, and throughout the rest of her life, creating a singular look that was as innovative as her art. “Everytime I put on clothes, I’m creating a picture,” she said of her “petite yet flamboyant” style. And just like her art, there was nothing predictable about her dress. On one occasion, she wore a plaid man-tailored shirt under a lavish and suffocatingly large mink coat, an enormous necklace of her own making, and her trademark Russian peasant scarf, which entirely concealed every strand of her thick head of short-cropped hair.

Most striking was the tuft of thick false eyelashes she had made from mink fur and cloaked her eyelids. As wild as this may seem, it did not detract from her natural beauty but accentuated it. As a young woman, she bore a striking resemblance to Greta Garbo. Those high cheekbones, sculpted jawline, strong nose, and sparkling eyes gave her a beauty that never abandoned her over the years. “I never feel age,” she once said. “If you have creative work, you don’t have age or time.” Toward the end of Nevelson’s life, designer Arnold Scassi created her wardrobe. When the expressionist portraitist Alice Neel asked how she dressed so beautifully, Nevelson, who was known to be sexually liberated, replied, “Fucking, dear, fucking.”

Nevelson led a normal childhood in Rockland, Maine. She attended public school, where she learned English (Yiddish was spoken at home), played basketball (she was captain of her team) and frequented the Rockland Public Library. There on display was a plaster cast of Joan of Arc, which so enthralled her that she determined that one day she would become an artist. “In the first grade, I already knew the pattern of my life. I didn’t know the living of it, but I knew the line. From the first day in school until the day I graduated, everyone gave me 100-plus in art. Well, where do you go in life? You go to the place where you got 100-plus.”

Nevelson with charred rafters from St. Marks in the Bowery.

Diamond in the Rough

After graduating from high school in 1918, she took a job as a stenographer in a local law office and there met Bernard Nevelson, a successful Jewish shipping businessman and partner with his brother, Charles, in the Nevelson Brothers Company. Bernard introduced Louise to Charles, and in June 1920, they married. Their wedding reception was held at the extravagant Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston. It soon became clear to Louise that she did not fit into the mold of a wealthy Jewish housewife and socialite. “My husband’s family was terribly refined,” she said of her wealthy, high society Jewish in-laws. Within their circle, you could know Beethoven, but God forbid if you were Beethoven.”

The couple moved to New York City, and Louise’s disappointment in her marriage was distracted by the energy she absorbed from the greatest city on earth. She flung herself into studying art, took acting, singing, and dancing lessons, much to the disapproval of her husband and in-laws. In 1922, she gave birth to her one and only child, a son, Myron (later called Mike, who himself would become a sculptor), and in 1924 the family moved to Mount Vernon in Westchester County, a wealthy commuters’ town just north of Manhattan. Feeling cut off from the artistic environment she had so enjoyed as a city dweller, her home life began to suffocate her.

After eight years of marriage, Louise was determined to be true to herself, and in the winter of 1932-1933, at the height of the Great Depression, she left her husband, taking her son with her. With no financial support from her husband, she found lodgings in a rat-infested neighborhood in lower Manhattan. “The freer that women become, the freer men will be. Because when you enslave someone, you are enslaved,” she said.

The couple divorced in 1941. Nevelson took comfort in living in squalor rather than compromise her independence. She was so poor that at night, holding her young son by the hand, she combed the wintry streets collecting fragments of discarded wood that she could burn for heat. She found beauty in some of those castaway pieces and began to create wood sculptures. For the rest of her life, she would explore abandoned factories, derelict buildings, and construction yards to find raw and discarded materials for her sculptures.

Installation view of Louise Nevelson: Black & White. 537 West 24th Street, New York, NY. February 1 – March 3, 2018. Photography Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy of Pace Gallery © 2018 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York.

An American Sculptor

“I was the original recycler,” she said of herself. “Anywhere I found wood, I took it home and started working with it, to show the world that art is everywhere, except it has to pass through a creative mind.” Years later, when she finally achieved international fame and had made millions, she said, bemused, “It gave me great pleasure to think that I could take wood, make it good, and make people like Rockefeller buy it with paper money.” Unable to support her son and pursue her career as an artist at the same time, Louise sent her son to live with her family in Maine, sold the diamond bracelet her husband had given her as a wedding gift, and set out for Munich, Germany, to study under the abstract expressionist painter Hans Hoffman.

Later, she would speak of her guilt over abandoning her son for art, even admitting she should never have become a mother. Two years later, Nevelson returned to New York and was reunited with Hofmann, who she continued to study with at Art Students League. There she met Diego Rivera, a superstar Mexican painter and founder of the Mural Movement, and began working with him on his mural, Man at the Crossroads, at Rockefeller Plaza. They had a short-lived affair that abruptly ended when it became known to Rivera’s wife, the fiery artist Frida Kahlo.

Nevelson embarked upon a new path and began studying sculpture under Chaim Gross. During this time, she also experimented with lithography and etching, but more and more her passion for sculpture overshadowed even her drawing and painting. In 1941, she held her first solo exhibition as a sculptor at the Nierendorf Gallery, until the death of the gallery’s owner, Karl Nierendorf, in 1947. Color was an important, even vital, component of expressionist art, and yet Nevelson chose to use none.

Profile of the artist in her winter furs. Nevelson was known for her unpredictable and outlandish wardrobe. Photograph by Pedro E. Guerrero / GuerreroPhoto.com

Bringing “dead wood junk to life”

Black, white, and the natural color of wood and metal were her palette; once, she painted an unnamed wooden sculpture teal blue; in the early period, when she experimented in prints and drawing, she incorporated red in her otherwise tonal, trademark palette. “But when I fell in love with black,” she said, “it contained all color. It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance. Because black encompasses all colors. Black is the most aristocratic color of all. You can be quiet, and it contains the whole thing.”

When it relates to paint, the textbook definition of black is “the presence of all color” and white, “the absence of all color.” Nevelson interpreted this in its simplest form. Following her death, Washington Post author Paul Richard wrote that she “preferred to work, as witches do, in the dream-time before dawn. She kept her windows shuttered. Her house was mostly black. The polished floors were black. The table in the dining room, that cat and kitchen sink were black. The matte black sculptures in the largest room, the space she called ‘the forest,’ made the dim light dimmer still. Nevelson—who brought dead wood junk to life—ruled that dark and labyrinthine realm like some grand queen of the night.” [April 19, 1988.]

There was a complex order that ruled over her realm. She committed herself mind, body, and soul to sculpture and sought a form of minimalist truth in shape, line, texture, and form. Louise Nevelson birthed her own movement as if from her very loins. This was a woman of vision—a vision that never wavered over the many years of her work. “My eye has a great many of many centuries,” she said shortly before her death at the age of 88. The war years were a dark time for Nevelson. Though her work received major attention from the press, her earnings were paltry, and she continued to live in squalor. “And I saw darkness for weeks,” she reflected on those times.“It never dawned on me that I could come out of it, but you heal. Nature heals you, and you do come out of it. All of a sudden, I saw a crack of light . . . then all of a sudden, I saw another crack of light. Then I saw forms in the light. And I recognized that there was no darkness, that in darkness there’ll always be light.”

Orfeo Throne, Louise Nevelson, 1984, silkscreen on fabric. Courtesy Farnsworth Art Museum / FarnsworthMuseum.org.

Found Objects

This began Nevelson’s cubist period. She continued to collect discarded items from abandoned places. “When you put things together, things that other people have thrown out, you’re really bringing them to life—a spiritual life that surpasses the life for which they were originally created,” she maintained. In 1943, the Norlyst Gallery held an exhibition of her sculptures called The Clown at the Center of His Work. The poor reception did not deter Nevelson, and she entered a period of surrealism, guided by her friend, Salvador Dali. It was then, in the 1950s, that she found her signature style. “I make collages,” she said of her wood sculptures. “I join the shattered world creating a new harmony.”

Throughout the 1950s, Nevelson exhibited her work extensively, but still, despite her growing popularity and critical acclaim, continued to struggle financially. To make ends meet, she taught art in Great Neck, Long Island, as part of a community art education program. Later, during another period of financial stress, she relocated temporarily to San Francisco to teach art. “I’ve taught,” she reflected, “and the first thing I did when I taught art was not to teach art.” In 1954, the Kips Bay neighborhood of New York faced demolition, and Nevelson was a familiar figure among the ruins, picking up scrap material.

From this came some of her most notable mid-century works: Bride of the Black Moon, First Personage, and Moon Garden + One, which were exhibited at the Grand Central Modern Gallery. By 1957, while financial recognition still evaded Nevelson and she subsisted on “cans of sardines and handfuls of raisins,” her big breakthrough finally occurred. She was made president of the New York chapter of Artist’s Equity (later elected national president) and joined the Martha Jackson Gallery, where her work sold out at spectacular prices. On top of all this, she was photographed for the cover of Life magazine.

Basil Langton. Louise Nevelson, ca. 1979. Louise Nevelson papers, circa 1903-1988. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

“Vibrations in the Universe”

In 1960, she gave her first one-woman exhibition in Europe, at the Galerie Daniel Cordier in Paris. Following that, a collection of her work, called “Dawn’s Wedding Feast,” was included in a group show called “Sixteen Americans” at the Museum of Modern Art. Curated by pioneering MoMA curator Dorothy Miller, Nevelson was the only woman in an all-star group that included Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella. “I’m a workhorse,” Nevelson admitted in one of her many recorded interviews. “I like to work. I always did. I think that there is such a thing as energy, creation overflowing. And I always felt that I have this great energy, and it was bound to sort of burst at the seams so that my work automatically took its place. With a mind like mine, I’ve never had a day when I didn’t want to work. I’ve never had a day like that. And I knew that a day I took away from the work did not make me too happy. I just feel that I’m in tune with the right vibrations in the universe when I’m in the process of working. In my studio, I’m as happy as a cow in her stall.”

In 1962, Nevelson made her first museum sale, to New York’s Whitney Museum, and in 1967, the Whitney hosted the first retrospective of her work. Featuring over 100 pieces, from drawings she made in the 1930s to her most recent sculptures, it was a huge success. In 1964, Nevelson created two of her most famous works: Homage to 6,000,000 and Homage to 6,000,000 II, a tribute to the victims of the Holocaust in World War II. Now her work was represented across the country and the world, and the money poured in. At the age of 65, Nevelson had finally arrived.

Inspiration, emotion, the overpowering feeling that you understand what an artist is trying to say through her work does not come easily to many who view Nevelson’s work. What everyone can appreciate is that she made order from chaos. By taking random, disassociated pieces and combining them into one fluid form, Nevelson was able to produce a single statement. No one sees the same thing in a Nevelson work, and many see nothing at all. To appreciate Nevelson, you must look beyond the surface. “A white lace curtain on the window was for me as important as a great work of art,” she once pointed out. “The gossamer quality, the reflection, the form, the movement. I learned more about art from that than I did in school.”

The Sky is the Limit

It is this minute ability to simply observe that is essential to appreciate Nevelson and her genius. That Nevelson believed herself to be a great artist cannot be argued. “There’s no denying that Caruso came with a voice, that Beethoven came with music in his soul. Picasso was drawing like an angel in the crib. You’re born with it.” And Nevelson was, too. In 1969, Nevelson completed her first outdoor sculpture, a commission from Princeton University in New Jersey. “Remember,” she said in an interview at the time, “I was in my early 70s when I came into monumental outdoor sculpture. I had been through the enclosures of wood. I had been through the shadows. I had been through the enclosures and come out into the open.”

Coming out into the open also opened the sculptor to new materials—Plexiglas and corten steel among them, which she proclaimed was “a blessing” in her work. And there was never an end to it. Barbarlee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, a New York talk show hostess, who called Nevelson “the doyenne of American sculptors,” and commented that “her work pours forth with uninterrupted regularity.” The height of her career came in 1975 when Nevelson accepted the commission to design the chapel of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in midtown Manhattan. The design of the sculpture, architectural ornaments, and even the vestments was a total expression of Nevelson’s soul.

Confronted during one interview about a Jew designing a Lutheran church, she commented that her work transcended all religious barriers. The chapel is entirely white. White, Nevelson said, “summoned the early morning and emotional promise.” Sometimes she spent years creating a work, as she did with Sky Cathedral, and Sky Cathedral: Night Wall, which took 13 years to build in her New York studio before finding its home in the collection of the Columbus Museum of Art. “This is the Universe, the stars, the moon—and you and I, everyone,” she said of the masterwork.

Woman, Child and Cats, Louise Nevelson, 1946, oil on canvas. Courtesy Farnsworth Art Museum / FarnsworthMuseum.org.

New York’s Own

But the one place of all where Nevelson’s work best belongs is New York City, a virtual garden of Louise Nevelson sculptures—enormous, towering structural works such as Night Presences (1972) on Park Avenue at 92nd Street, Shadows and Flags (1977) at the Louise Nevelson Plaza, Sky Gate, New York (1977-1978) at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and Untitled at Riverfront Apartments at 420 East 54th Street. Nevelson’s public artworks can be found in museums, art centers, universities, and performing arts centers in Arizona, California, Connecticut, Washington D.C. (Smithsonian Institute), Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York State, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and Virginia.

Nevelson was the subject of great photographers, including Richard Avedon and Robert Mapplethorpe. In 2000, the United States Postal Service released a series of commemorative postage stamps in her honor. She was bestowed honorary degrees by the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Brandeis University, Harvard University, Rutgers University, and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and was presented the 1985 National Medal of Arts by President Ronald Reagan and the Edward MacDowell Medal for her contribution to American culture and the arts. The Farnsworth Art Museum in her hometown of Rockport, Maine, houses the second largest collection of her works, which includes one-of-a-kind jewelry.

In 2002, the late, great actress, Anne Bancroft, was set to star in “Occupant,” a biographical play about Nevelson written by her friend, playwright Edward Albee (“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf.”) However, Bancroft was diagnosed with pneumonia, and the play never made it past preview performances until it was resurrected by the Signature Theatre Company in 2008. The woman who suffered guilt over being a mother in fact gave birth to the Feminist Art Movement. “Another thing about creation is that every day it is like it gave birth, and it’s always kind of innocent and refreshing. So, it’s always virginal to me, and it’s always a surprise. Each piece seems to have a life of its own. Every little piece or every big piece that I make becomes a very living thing to me, very living. I could make a million pieces; the next piece gives me a whole new thing. It is a new center. Life is total at that particular time. And that’s why it’s right. That reaffirms my life.”

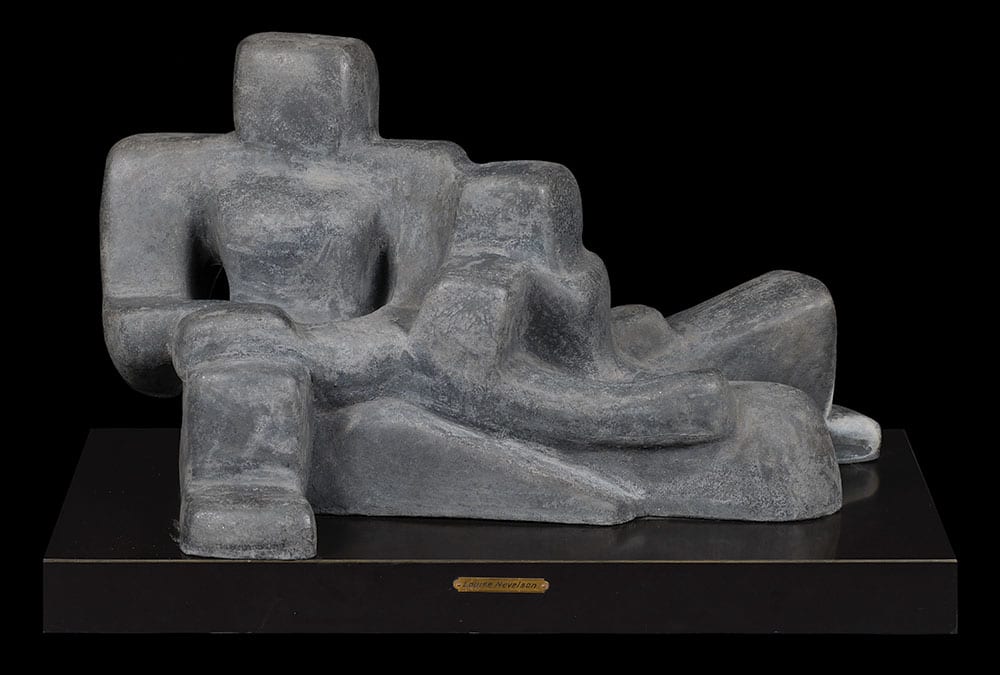

Two Women, Louise Nevelson, 1933, cast aluminum sculpture on wooden base. Courtesy Farnsworth Art Museum / FarnsworthMuseum.org.

Her life ended April 17, 1988, when she died in her SoHo apartment at the age of 88 after several months of illness. Until the end Nevelson maintained, “I still want to do my work. I still want to do my livingness. And I have lived. I have been fulfilled. I recognized what I had, and I never sold it short. And I ain’t through yet.” She isn’t through yet. Nevelson will never be through yet. Her spirit, her example, lives on. “In Nevelson’s case,” Don Bacigalupi, former president of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, wrote, “she was the most ferocious artist there was. She was the most determined, the most forceful, the most difficult. She just forced her way in. And so that was one way to do it, but not all women chose to or could take that route.” Choose. Learn. Persevere. Follow your own route and stay the course. Louise Nevelson did.

Written by Laurie Bogart Wiles

This post was first published Sep 23, 2020