By Latria Graham

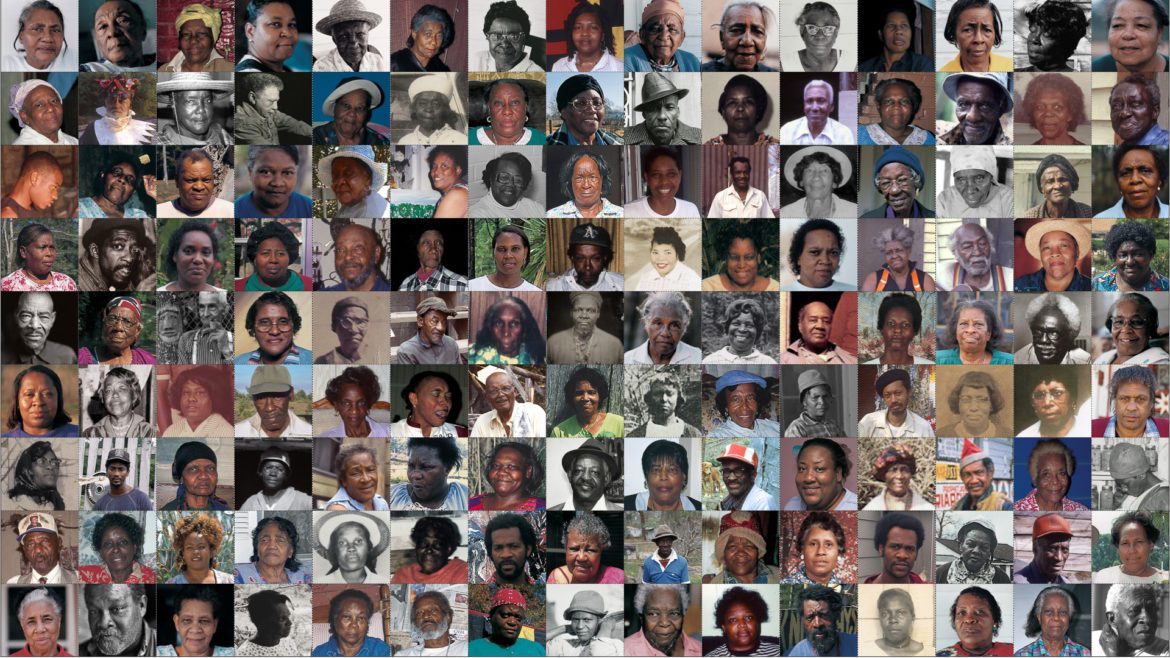

HOLDING THE LARGEST COLLECTION OF WORKS BY AFRICAN AMERICAN ARTISTS FROM THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES, THE SOULS GROWN DEEP COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP & FOUNDATION IS REDEFINING THE CANON OF AMERICAN ART.

Down in the north-central section of Wilcox County, Alabama, sits a little parcel of land. Five miles wide, seven miles long, and surrounded by the Alabama River on three sides, this area is known as Gee’s Bend, population 275. An hour’s drive from the county seat of Camden, which is the closest source of food and medical services, the area is geographically cut off from the world. Mostly left to themselves for nearly 100 years, this close-knit historically all-black community’s folkways and traditions survived well into the twentieth century and stand as a symbol of their resourcefulness during a time of great duress.

Artelia Bendolph in the window of her house, Gee’s Bend. Arthur Rothstein, 1937.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ARTHUR ROTHSTEIN/COURTESY FARM SECURITY

ADMINISTRATION/OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION COLLECTION, PRINTS

AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Art admirers from all over the world come to this patch of fertile soil in Alabama’s Black Belt to get a glimpse of the artistic legacy of four generations of Southern quilters. Initially created for the practical purpose of keeping warm, the quilts created by the women of this region are known for their unexpected color combinations, bold patterns, and improvised designs. Though many are individual artists, the group is often referred to as the quilters of Gee’s Bend.

The area was named after Joseph Gee, who built a plantation on the peninsula in the early 1800s. In the 1840s, the Gee family sold their land to Mark Pettway, and he continued to operate a plantation there. After emancipation, the residents of the area worked the land as tenant farmers. With little material wealth to buy goods, families had to find a way to keep warm. Quilts made corn husk mattresses bearable and provided more warmth than their sheets made of fertilizer sacks. These quilts were the Gee’s Bend’s women’s way of recycling. At a time when they could not afford to let anything go to waste, they repurposed fabrics. When a piece of clothing was well past mending, it was deconstructed and placed into a quilt. Plaids and prints find a way to work together. Squares and rectangles were cut from old work shirts. Old dresses of chambray and gingham were given a new life and worn-out jeans would sometimes frame the edges.

As they worked, they breathed new life into the fabrics they found, taking the mundane materials and transforming them into art. The philosophies and subjects of the quilts vary from artist to artist, but meditations on equality, peace, hope, justice, truth and love can be found in their creations. Many families make their own versions of some of quilting’s standard patterns. Bricklayer, housetop, log cabin, nine patch, wedding ring, and bear claw designs can be found, but some artists eschew traditional designs completely, creating striking, bold, imaginative creations from a dream they had one night or a vision they received while sitting under the chinaberry tree.

African American quilts, vicinity of the Alabama River (possibly Gee’s Bend), Wilcox County, Alabama. PHOTOGRAPH ATTRIBUTED TO EDITH MORGAN, CIRCA 1900

The community’s story is woven into these works of art. From the hardships endured during enslavement to the unfair penalties that came with sharecropping and the harrowing upheavals of the civil rights struggle, quilting is, for these women, an act of remembering. The cloth they often quilt with is imbued with the memory of the person who wore the clothes and may have already passed on. Materials and techniques changed over time. Placed in the context of American art canon, these pieces became a study in the visual social history of a people and place over the course of a century.

Inspired by the message of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., when he came to Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, several of the community’s residents registered to vote. Many were punished for desiring to exercise their civil liberties and were fired from their jobs or lost their homes. Francis X. Walter, an Episcopal priest and civil rights organizer during the 1960s, saw the area’s quilts as a way to earn income. The community established the Freedom Quilting Bee, a quilting cooperative. Saks Fifth Avenue and Bloomingdales began carrying their work, but the department stores desired uniformity, which did not suit the creative direction of many of the women. By the 1980s the quilts were out of the public eye again.

In the mid-1980s, William S. Arnett, an Atlanta-based writer, editor, curator and art collector, began to collect the work of black artists in the American South. In the 1990s, Arnett began a scholarly examination of the visual traditions of African Americans in the region. The result of his efforts was a two-volume book titled Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South. During this time, he stumbled upon a photograph of a quilt draped over a woodpile. The artist in the photo was a woman by the name of Annie Mae Young. He set off to find her. She told him about Gee’s Bend, where he discovered a trove of quilts. These works were exhibited at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts in September 2002 under the title The Quilts of Gee’s Bend.

Raina Lampkins-Fielder, Curator of Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Community Partnership. PHOTOGRAPH ANA BLOOM

This exhibition showcased over 60 quilts made between 1930 and 2000. Glorified for their beauty and originality, art critic Michael Kimmelman of The New York Times hailed the collection as “some of the most miraculous works of art America has produced.” After breaking attendance records at the museum, the exhibition embarked on a three-year, coast-to-coast, 12-venue tour. Stops included the Smithsonian, the Whitney, and other major American art museums in cities like Atlanta, Minneapolis, and San Francisco. Recognized by museums and art experts for their elaborate quilts, on August 24, 2006, the artists of Gee’s Bend were honored with a series of commemorative stamps as part of the American Treasures series, which is meant to showcase beautiful works of American fine art and crafts.

The artwork collection Arnett amassed during his studies includes 1,100 works of art by 160 African American artists. In 2010 the Arnett family created the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an Atlanta-based nonprofit. The organization advocates for previously ignored artists of color who made artworks born in the struggle for civil rights. For the last five years, the foundation’s goal has been to pursue social, racial, and economic equity by promoting economic development in the Black Belt and creating access to basic needs including health care and education.

The foundation’s four-person staff takes steps to reconnect artists with news of and plans for their creations. Making the artists part of the process ensures that they have creative control and can dictate how images of their work are used and can receive any income from the use of their art. In the age of fast fashion, commercialization, globalization, and social media, the opportunity for exploitation is everywhere. Social media is full of goods inspired by the community’s aesthetic, and there are plenty of Gee’s Bend imitations. Souls Grown Deep Foundation works to preserve art in the African American South by placing the collection’s creative works into the permanent collections of leading art museums.

“It’s a very challenging part of the world,” Maxwell Anderson, the president of Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Community Partnership, says of Gee’s Bend. “There are houses, but the majority of people’s circumstances are really dire. There was a United Nations representative who visited this part of Alabama a few years ago and said he couldn’t believe that in the developed world people were living in these conditions. Part of what we’re trying to do is—after many years of promises from people to help this community—we’re trying to have a laser-like focus on a series of endeavors that can actually improve life there.”

For him, that means making sure the artist’s artwork is valued correctly. Raina Lampkins-Fielder was the head of education at the Whitney Museum of Art when the Gee’s Bend quilt exhibition came to New York City. Now she serves as the Curator of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and Community Partnership and sees correcting the record to include the quilters of Gee’s Bend as a social justice initiative. “Notions of art and artifacts, ideas of folk art, the women as artisans—these are all things that the organization is beginning to question—that terminology. In some ways these [terms] are not incorrect attributions or ways of speaking about categorizing art,” she explains. Still, she mentions that the way art is talked about determines its value, and certain categories present barriers for artists outside of the culture’s circle. “One of the goals that we have with Souls Grown Deep is really to look at why these artists had not been included, why they have been disenfranchised,” she says. “There’s a very obvious kind of institutional and systemic racism. It’s about the kind of bias about this particular region in the South not being quite as cultivated. You also have categorizations of artists that, while in some ways they’re helpful in other ways, are going to constantly position them in a space. Calling someone a ‘folk artist’ and not an ‘artist’ will absolutely determine their worth. It will determine who has access to see their work—the fair as opposed to the museum. [This art] should be in both,” she insists.

Lampkins-Fielder also mentions that the academy’s struggle to see artists like the ones they represent as worthy of recognition makes it challenging for scholars, curators, and people in education to use this work as part of their research or just anchor the artists in the larger conversation of American art.

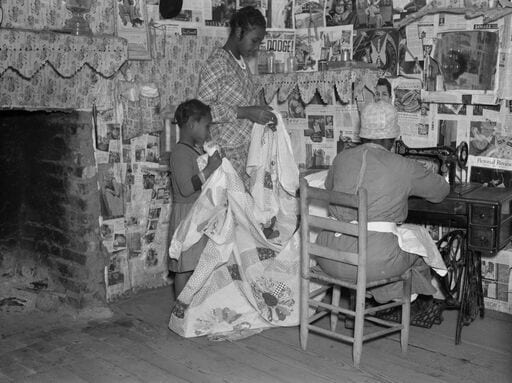

Gee’s Bend quilter, Lucy Mooney and family. 1937. PHOTOGRAPH BY ARTHUR ROTHSTEIN/COURTESY FARM SECURITY ADMINISTRATION/OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION COLLECTION, PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

“We’re really trying to change that narrative,” she says. “The art market is very cruel to artists who don’t have the requisite background in formal education and connections, ascendancy and society,” Anderson says. “It took a long time to start putting in place a means by which these artists would be seen in the museum culture. I’ve spent a lot of time in and out of the South trying to expand the canon of American art history to include these artists. We look at museums as our partners. We have now 20 leading art museums coast to coast that have acquired work from us. And we anticipate having another 30 or 40 museums nationally and internationally in the next few years acquire work,” he adds.

Souls Grown Deep Foundation’s board member Lola C. West experienced the art world’s disconnect firsthand. “When I was in junior high, I had a black art teacher, and he liked my work,” West says. “So he would exhibit it in the school, and then he recommended me for honor art class in high school. When I got to high school, on my first day of honor art class, this white male teacher asked us to draw something. I drew. He came by my desk and he said, ‘You call that art?’ That was the end of me and art forever.”

The last r comes out of her mouth echoing the sense of finality. “I am at heart an artist,” she muses, thinking back on the moment when she decided to put down her pencil. “I have a deep love for art, and my entire apartment has always been nothing but black art.”

The walls of her Manhattan home are covered from floor to ceiling in pieces by black artists, and she is amazed by the resourcefulness of the quilters down in Gee’s Bend. So, when the opportunity came to support their work, she took it. Mary Margaret Pettway was born down in the Bend. A third-generation quilter, the now-famous works of art were always part of her reality.

“When we were babies, we were wrapped in the quilts,” Pettway explains. “When we became children, we would be up under the quilts, threading needles and passing them back through the quilts when they were needed.”

The girls are 9 or 10 when they start helping with the quilts. “You would start sewing on the ends of the quilt, and if the stitches didn’t meet where your mama or grandmama wanted them to, you’ve got to take them out and do them again,” she says with a laugh. By 12, many were working on their first full pieces. This is where Pettway learned her skills, seated at the feet of God-fearing wise women who discussed politics and Bible lessons as they sewed. They exchanged recipes and talked about their fears. Her mother, Lucy T. Pettway, was a perfectionist, and one of her pieces, Birds In the Air, is housed at the High Museum in Atlanta. Knowing her mother’s artwork is appreciated by art enthusiasts gives her a sense of pride.

Mary Margaret Pettway (Souls Grown Deep Board Chair) and Shontaye Mosely. © STEPHEN PITKIN/PITKIN STUDIO

Not content to follow in her mother’s footsteps, she works in something many wish to move away from. “It’s something to put up a quilt,” Pettway explains. “You quilt it out, clip it, hem it and trim it. They don’t want the labor-intensiveness of it.” When The Quilts of Gee’s Bend exhibition opened in Houston in 2002, the quilts took on a new meaning for Pettway. When she learned that the exhibition routinely broke museum attendance records, she finally understood the visual and aesthetic power of what her family created.

“That was pure pride,” she says. “I knew we had finally made it at that point.”

During the recent reveal of the Obama portraits at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Pettway’s pride only grew. In the iconic portrait of Michelle Obama, painted by African American artist Amy Sherald, Mrs. Obama’s dress dominates the frame. The ensemble was designed by Michelle Smith, founder of the label Milly. Its geometric print, which mixes rectangles, triangles and circles, resembles the quilt masterpieces made by the women of Gee’s Bend. Sherald’s intentional choices sparked much discussion and acclaim, situating the culture and social history of the artists of Gee’s Bend in a way that allows the greater public to learn more about the quilting collective and cultivates more discussions about the art. With the help of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, art enthusiasts can keep coming to Gee’s Bend to learn more about the creativity, determination and survival of this community and their place in the narrative of contemporary American art.