By Latria Graham

Grete Stern always identified as an artist. From the time she was a small child, her mother enjoyed showing Grete’s talents to friends. Born on May 9, 1904 in Wuppertal-Elberfeld, Germany, she became a skilled musician, playing piano and guitar. When it was time to go off for an education, Stern attended Kunstgewerbeschule (Am Weissenhof) in Stuttgart, studying graphic design under Ernst Schneidler. In 1926, she began working as a freelance graphic design and advertising artist in her hometown of Wuppertal. (Her early work demonstrates some of the collage work she would later refine as a photographer.) In DLH from 1925, a woman in a red hat stares upward at a plane soaring perilously close to her face—the proximity and scale is an illusion but created so seamlessly that this encounter between ordinary things seems surreal.

A serendipitous encounter with a new art form would change the direction of Stern’s life. “One day, I saw an exposition of photographs,” Stern recalled in the 1995 documentary Ringl and Pit by Juan Mandelbaum. “I had never thought about [photography], you see. It was Outerbridge and Weston.” Paul Outerbridge and Edward Weston’s work in the mode of photography showed her the shortcomings of her graphic design work: “I was always interested in being able to design faces. What I could do didn’t satisfy myself. When I saw those pictures, I knew at once that I wanted to learn that. So I left my mother and went to Berlin.” It was 1927. A small inheritance allowed Stern to give up her job, acquire a small apartment, purchase a Linhof camera and pay for private lessons with Walter Peterhans, famed German photographer and teacher at the Bauhaus.

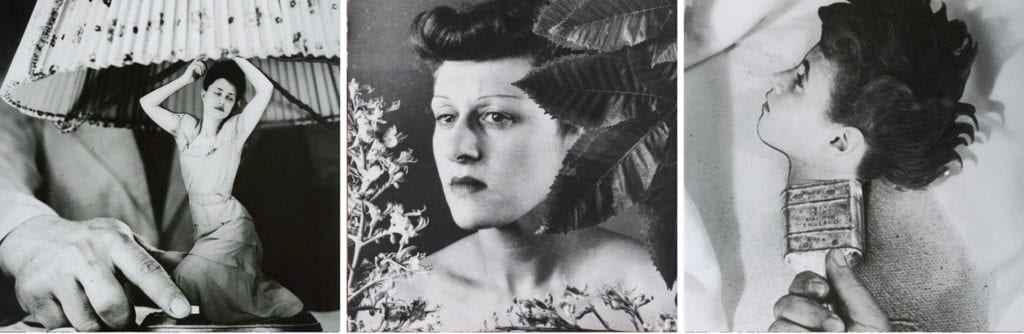

Her 1948 controversial work, Articulos electricios par el hogar (Electrical appliances for the home), Self-portrait of Grete Stern, 1956. Dream 31.

Photos courtesy of Art Basel Jorge/Mara-La Ruche

In 1929, Ellen Auerbach was also searching for a new start. Raised in a conservative family that provided little financial or emotional encouragement for her art, Auerbach studied sculpture at the Academy of Art in Stuttgart. Two years into her practice, she decided to change modes to photography. She came to the city with her 9x12cm camera, a token of appreciation from an uncle, who cherished the sculptured bust that she created in his likeness, and sought out a teacher. She also found Peterhans and tried to get him to take her on as a student, but he insisted he already had one—by the name of Grete Stern. After some convincing, Peterhans took on Auerbach too. Stern would show her the basics, and he would teach her technique. “She looked grown up—I felt like a small child next to her,” Auerbach remembered in the documentary. “She just impressed me, and I was a little scared of her because she had more strength—she was more serious than I was.” In this way, Ellen Auerbach met Grete Stern, and in a few short years, they would use their innovative style to change the commercial advertising landscape in central Europe.

Under Peterhans, the pair would learn the basics of what would be known as the Bauhaus basic design philosophy— lighting, geometry and the place where form and function merge. He taught his students to find beauty in the commonplace. In 1930, when their instructor moved to Dessau to become the master of photography at the Bauhaus School for art and design, Auerbach and Stern chose not to follow. Instead, they decided to open their own photography studio.

“There were women photographers,” Stern said of the time period.

“But that two would work together,” Auerbach interjected, “and make the pictures together, that amazes everybody.” Their enterprise needed a name. They decided against Ellen and Grete because that immediately noted gender in a male-dominated field. Using their last names sounded too commercial for their bohemian undertaking. The women eventually decided on Ringl+Pit, based on their childhood nicknames—Stern was Ringl and Auerbach, Pit. Every photograph is signed with both names, and the women worked together so closely that sometimes they could not remember who took the photograph or whose body parts were used to model the products in the pictures.

Their studio dabbled in portraiture, advertising and fashion photography. The studio soon established itself as among the most innovative in Berlin. Its portraits were renowned for their originality, and manufacturers of everything from cigarettes to petroleum products went there. Stern and Auerbach designed book jackets and enjoyed creating publicity spreads that appeared in the most prominent magazines of the day.

Sueño (dream) Nº 12, 1948, courtesy of Art Basel/Jorge Mara-La Ruche

The early 1930s were marked by experimentation and change because of the great political upheaval and turmoil taking place in the Weimar Republic, where the women lived. Indeed, the concept of the “Western woman” was undergoing a radical shift. Stern and Auerbach were part of the first generation of women who could move to the cities, work and lead independent lives—dubbed the “new woman” movement. Embodied by flappers and actresses like Marlene Dietrich, this “new woman” bought her own wares instead of appealing to her husband to buy them for her—and that changed the nature of advertising campaigns.

The Ringl+Pit collaboration represented a departure from current styles by combining objects, mannequins and cut-up figures in a whimsical fashion. The pair experimented with a mix of photomontage, collage and typography, crafted in a studio setting. They brought their playful and Dada-inflected graphic style to ad campaigns for hair dye and perfumes.

Using mannequins, wigs and other symbols of femininity, Stern and Auerbach worked to question the artifice and masquerade of feminine identity. In the 1930s, Ringl+Pit’s work received positive reviews in the magazine Gebrauchsgraphik. Pétrole Hahn, a 1931 advertisement for a hair lotion, features an old nightgown, a mannequin head and a real hand.

Komol, created in 1932, was also an advertisement for a hair lotion. The work won first prize at the Deuxiême Exposition Internationale de la Photographie et du Cinéma in Brussels. Stern’s graphic design specialty and Auerbach’s humorous and ironic touches added a subtle irony in their work about what was accepted and expected of women.

In 1933, the rise of anti-Semitism in Germany meant that Berlin was no longer safe for two Jewish female photographers, so their physical studio was disassembled. Ellen relocated to Palestine, and Grete moved to London with her soon-to-behusband and fellow photographer, Horacio Coppola. Ahead of the Abyssinian War in 1936, Auerbach visited Stern in London. They collaborated on a few commissions. One advertisement, for a maternity hospital, was their final work together.

It became increasingly clear that London would not be a safe haven. Commissions ceased, and the creative landscape became more and more limited. Ellen Auerbach made her way to the United States, landing in Philadelphia. Grete Stern and Horatio Coppola made their way to Buenos Aires, Coppola’s hometown.

In the summer of 1935, two months after arriving in Argentina, Stern and Coppola mounted an exhibition in the offices of the avant-garde magazine Sur, which called their work “the first serious exhibition of photographic art in Buenos Aires.” Before this, portraits and even landscapes were done with flat lighting, simple poses and untouched negatives. The Bauhaus School’s sensibility shook up Argentina’s stilted approach and established Coppola and Stern as two of the founders of Argentine modern photography.

The couple built a house by progressive architect Vladimiro Acosta in the Ramos Mejía neighborhood. Their address became a mecca for a new group of writers and artists, including Madi, a coalition of artists who stood in opposition to Juan Domingo Perón. Their marriage produced a daughter, Silvia, and a son, Andres. In Buenos Aires, Stern took numerous portraits of the city’s intelligentsia, including writers like Amparo Alvajar, Jorge Luis Borges and Pablo Neruda. In addition to her iconic portraits of Bertolt Brecht and Karl Korsch, she photographed a number of painters and dancers, many of whom were also in exile for being anti-Fascist.

Stern and Coppola operated a graphic design, photography and advertising studio in Buenos Aires from 1937 to 1943. Although they attempted to create a modern studio, their way of working was too far ahead for the city’s sensibilities, and it folded. After the couple divorced in 1943, Coppola abandoned photography.

Stern continued to live in the house they built, surrounded herself with contemporary artists and continued to take their portraits. The work she created after her divorce is arguably her most famous. In 1948, popular Argentinian women’s magazinem Idilio commissioned a series of illustrations called Sueños, or Dreams, for their weekly column titled “El psicoanálisis le ayudará” or “Psychoanalysis will help you.” The section invited readers to submit their dreams for analysis, and their musings would be illustrated with a photomontage by Stern.

The resulting work portrays women’s dreams, co-opted by the unfulfilled promises of the Peronist regime with a disembodied urgency and surrealist strangeness. Anxiety, domination and entrapment were common themes. Bodies are shrunken or enlarged. Distorted perspectives give the effect of insecurity. These protofeminist works and Alice in Wonderland-like scenes were a creative outlet for her thoughts and impressions of life as a woman in her adopted country, translating the unconscious fears and desires of its predominantly female readership into clever, compelling images.

In Dream 44, a woman sits in a bird cage, fan in front of her face. No door is visible. In Dream 32, a female mountaineer is dangling on a rope, hanging from a cliff in her floral summer dress and 3-inch heels. In Household Electronics, created in 1949, a woman’s silhouette props up a lampshade as a man reaches to “turn on” the tiny, elegantly dressed woman. Her allusions to bondage and predation suggest that the source of most dilemmas is male authority. Household Electronics is one of her most famous collages.

Stern added to her Sueños series until 1951, producing around 150 photomontages of repressed and oppressed women struggling in Argentina’s male-dominated culture. When that commission ended, she took a job with the Buenos Aires urban planning agency, documenting the city’s architecture using her photography skills for what she called “a social function.” In 1958, Stern became an Argentine citizen, and the next year she relocated to Resistencia to work as the photography teacher at the National University of the Northeast. In the 1960s, her interest in native cultures led her to produce various photographic documentaries in the Gran Chaco region. She worked for the city’s fine arts museum until 1970 and continued to teach until 1985, when she retired from photography altogether.

In 1993, a historical book entitled Ringl + Pit was published in Germany. An exhibition of the same name toured a number of German cities as well as London. Filmmaker Juan Mandelbaum made a documentary about Ellen Auerbach and Grete Stern, entitled “Ringl and Pit” in 1995, and the old friends are reunited on screen, still filled with that visceral magnetism that made them artists, talking about the ways they played on the traditional codes of commercial photography to produce innovative and humorous images.

Grete Stern died in Buenos Aires in 1999, at the age of 95. (Auerbach died in 2004 in New York City.) Several retrospective exhibitions of Stern’s work have been held in Buenos Aires, Berlin, London and New York among other cities.