Hunting images hidden in the Louisiana bayous

By Abby Deering

Photographs by Nell Campbell

As a young woman living in New Orleans, Nell Campbell scanned the obituary page of the Times-Picayune, looking for jazz funeral listings. She would call in sick to work, grab her Pentax Spotmatic and follow the boisterous procession on the streets, hoping she wasn’t spotted on TV by her co-workers.

“I think of myself as a recorder,” Campbell says, “a documentary photographer.”

Nell Campbell, right, with friend Charles Khoury, after a duck hunt in Southwest Louisiana 1976.

Two major themes — the documentation of Louisiana and political activism and protest — run throughout Campbell’s photographs, a body of work spanning more than 40 years. Her photographs give voice and form to life in the margins.

In Campbell’s words: “I have been motivated by subjects concerned with cultural representation and issues of social justice.” Her work spans anti-war demonstrations from Vietnam to Iraq; LGBT Pride parades and marches across the country (an ongoing project begun in 1977); and portraits of campesinos at work in the tobacco and sugar cane fields of Cuba.

“None of these projects are acute incidents but rather subjects I have been documenting over a period of years.” In many ways, her longest-standing documentary subject has been her home state, Louisiana.

Campbell has been based in Santa Barbara, California, since attending the Brooks Institute of Photography, but she has returned home to Louisiana throughout her career, producing a six-year study on Mardi Gras in New Orleans; a series of panoramic landscape photos of the wetlands in southwestern Louisiana; documentation of the aftermath of hurricanes Katrina and Rita; and a 14-year photo project on duck blinds along the Calcasieu River and its adjoining bays.

“I have a cultural and historical life connection to the geography of Louisiana, much stronger than to Californian geography, even though I’ve lived here longer,” Campbell said. “I think where you grow up has a different meaning.”

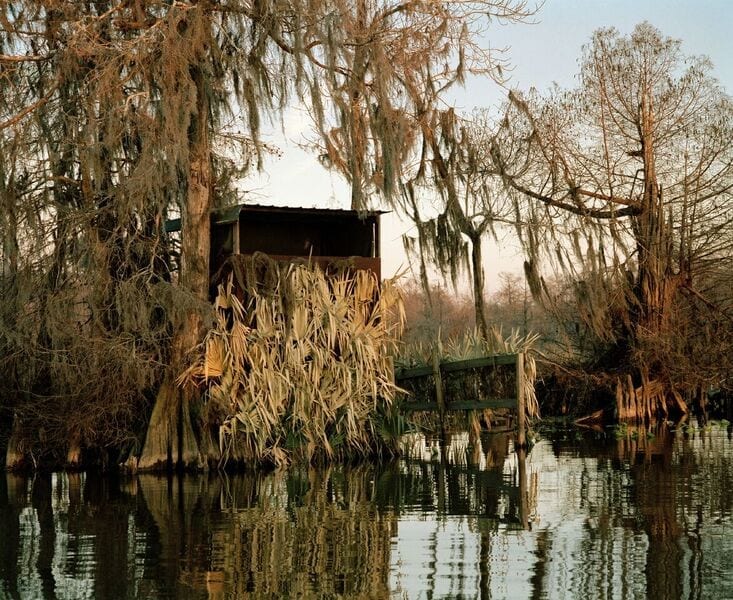

Moss Bluff Bay I, Dec. 2001.

Campbell grew up in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and spent much time as a child on the Calcasieu River and its tributaries. It’s a body of water she knows intimately. “When I was 5, my mother took me fishing on the banks of the West Fork of the Calcasieu and let me fish all day with an unbaited hook because she couldn’t bear to touch the worms — worms that she and I dug up from under the branches of the oak tree in our backyard,” Campbell recalls. “I know all the bends and turns of this river from water-skiing as a teenager and from crossing it on the small West Fork ferry as a child and from crabbing on the Calcasieu, catching the crabs we added to our gumbo supper.”

The duck blind project began during a visit home in 2001 when good friends took her on a boat ride, pointing out blinds they spotted while fishing. Standing on the bow of the flat-bottomed boat, Campbell began photographing these indigenous structures. It became a quiet obsession. Every time Campbell returned home, she set out again to revisit the blinds deep in the bayous, accessible only by boat. The project now spans 14 years and is comprised of more than 100 photographs.

Duck blinds, a form of vernacular architecture particular to the bayous of Louisiana, are built by the hunters who use them — providing necessary shelter and camouflage while they await the arrival of ducks and geese. These hideouts are fashioned by hand with scrap lumber, flotsam and jetsam carried by the streams, and native plant material: palmetto fronds, Spanish moss, roseau cane and river foliage. “Cypress and other trees are used as part of the structural framework, except in shallow water where wooden supporting posts may be driven into the muddy river bottom,” Campbell said. “Sections of the framework may be assembled on land and brought in by boat or the entire blind may be assembled on site.”

Campbell’s images of the blinds are arresting, referencing romantic landscape traditions and evoking a sense of the sublime. They are also haunting, reminiscent of Gothic scenes of ruination – the Southern Gothic, in particular.

The deep tones and rich hues of Campbell’s photographs, their supreme sense of stillness, heighten a sense of discovery for the viewer.

“Watermelon Bay I,” March 27, 2004.

Campbell presents the blinds found on her beloved Calcasieu River as a counterpoint to those found in the swamps. While duck hunting is considered to be “better” in the swamps, it costs money to hunt in these environs, attracting a middle class clientele, and the blinds consist of manufactured prefab structures. In other words, a certain spirit of resourcefulness is lost. On the river, a public waterway where it doesn’t cost money to hunt, there’s a variety of blinds styles. No two blinds are the same. They are idiosyncratic. An inventive interplay with nature, borne out of necessity, translates into a time-honored tradition that is aesthetically more sophisticated and enriches the cultural and physical landscape of Louisiana.

A discussion surrounding the politics of visibility has always been present in Campbell’s work — she finds life on the fringes and puts it center frame — however, in this body of work, it’s almost with an ironic twist, given the purposefully concealed nature of her subject, the blinds.

Campbell’s photographs do the important work of bearing witness. She’s told there aren’t as many of these kinds of blinds as there used to be. Her photographs articulate the unseen — they are testimonials of a way of life and of folk practices that may soon disappear altogether.

(Pictured in header: Calcasieu River & Watermelon Bay, March 2004.)